The time for the U.S. House of Representatives to initiate an inquiry into the question of whether President Donald J. Trump should be impeached is now.

The time for the U.S. House of Representatives to initiate an inquiry into the question of whether President Donald J. Trump should be impeached is now.

Those, who suggest that the U.S. House of Representatives should await a formal report from Special Counsel Robert Mueller before passing a resolution that would authorize the House Judiciary Committee to initiate an impeachment inquiry, ignore both the U.S. Constitution and historical precedent.

The same is true with respect to those, who suggest that percipient witnesses, like Michael Cohen, could, when appearing before Congress, refuse to answer questions if those questions touched upon the same subject matter that is a topic of Mueller’s investigation...

Constitutional Prerogatives

The Constitution confers upon the U.S. House of Representatives "the sole Power to Impeach".

"In all prior impeachment proceedings, the House has examined the charges prior to entertaining a vote", according to a 2005 Congressional Research Service overview [PDF] of the impeachment process. "The focus of the impeachment inquiry is to determine whether the person involved has engaged in treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors".

There is nothing in the Constitution which suggests that the Congress must await the outcome of criminal proceedings before initiating an impeachment inquiry. To the contrary, the Impeachment Judgment Clause expressly provides that after the process, "the Party convicted [by the Senate] shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment according to law."

Although this author and several constitutional scholars have argued that a President could be indicted and subjected to a criminal trial while in office, to date, the U.S. Department of Justice contends otherwise. So long as the DoJ refrains from indicting a sitting President, an immediate impeachment inquiry could serve to expedite the administration of justice. And even if, as we've argued, a President may be indicted while in office, constitutionally there is no reason why Congress, as a separate but co-equal branch of government, could not contemporaneously exercise its power to conduct an impeachment inquiry.

Precedent

In the past, Congressional and Special Counsel/Prosecutor inquiries have proceeded simultaneously.

As part of its oversight function, on May 17, 1973 --- two days before former Solicitor General Archibald Cox was appointed to serve as Special Prosecutor --- the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaigns (often referred to as "the Watergate Committee"), chaired by the very able Senator Sam ("I'm just an old country lawyer") Ervin (D-NC), conducted its first publicly televised hearing.

The Senate Watergate Committee's hearings served to inform the paths that would subsequently be pursued both by the Special Prosecutor's office and by the House Judiciary Committee.

During his June 1973 testimony before Senator Ervin's Committee, former White House Counsel John Dean implicated President Richard Nixon in the Watergate cover-up. Then, when he testified before the Committee on July 16, 1973, Alexander Butterfield, who served as Nixon's Deputy Assistant from 1969-1973, revealed that he oversaw the installation of a voice-activated audio-taping system in the Oval Office.

Dean’s and Butterfield's Congressional testimony provided the evidence the Special Prosecutor's Office needed to obtain and enforce a court order for Nixon to turn-over what proved to be the "smoking gun" audiotape. That audiotape cemented the charge of obstruction of justice.

With House impeachment and Senate conviction a virtual certainty, Nixon resigned on Aug. 9, 1974 --- a scant three months after the House Judiciary Committee's first publicly televised impeachment inquiry hearings.

The House Judiciary Committee's formal impeachment inquiry began after the House passed H.Res. 803 on Feb. 6, 1974 by a 410-4 roll call vote. The Resolution authorized the the Committee "to conduct an investigation of whether sufficient grounds exist to impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States." In the view of the Judiciary Committee's Chairman Peter J. Rodino (D-NJ), members of the Committee had an "inescapable responsibility" to conduct the inquiry.

In 1973-74, Congressional inquiry enhanced rather than impeded the course of the concurrent special prosecution. The real interference came only when President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon, who had already been named an un-indicted co-conspirator. That pardon prevented the accountability envisioned by the Impeachment Judgment Clause. Ford's dangerous move effectively created a Presidential impunity that was an affront to the words that appear above the entrance to the Supreme Court: "Equal Justice Under Law."

Comity

It is, of course, common sense that Congress, in performing its oversight and impeachment functions, should take care to avoid unduly interfering with the law enforcement functions assigned to the Special Counsel, as occurred during the Iran/Contra hearings when Congressional grants of use immunity led to the overturning of the criminal convictions against former National Security Advisor, Admiral John Poindexter, and his assistant, Lt. Col. Oliver North.

It is appropriate that elected representatives confer with the Special Counsel so as to avoid such untoward results. But it is inappropriate for Special Counsel or anyone else to ask that Congress --- one of three co-equal branches of government --- refrain from performing its Constitutionally assigned function to initiate and conduct a fair, impartial and public impeachment inquiry. There is no "the Special Counsel doesn't want me to answer" testimonial privilege.

Fairness/Public Awareness

While there is ample evidence that would support the initiation of an impeachment inquiry with respect to President Donald J. Trump, that inquiry cannot be considered fair or impartial unless the House Judiciary Committee begins its inquiry by extending to the President a presumption of innocence. In concert with the solemn oath they took to support and defend the Constitution, Committee members must pursue the facts wherever they may lead, and must ultimately issue their recommendations solely on the basis of the evidence; irrespective of political considerations as to how a Republican-controlled Senate may or may not vote following an impeachment trial.

Should a Republican-controlled Senate refuse to convict in the face of compelling evidence of the President's guilt, publicly disclosed over the course of House Judiciary Committee hearings and a Senate trial, the ultimate judgment can be rendered by an informed electorate in the next election. That's as it should be. In a democracy, it is the People who are sovereign.

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

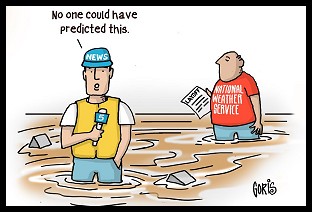

Sunday 'Totally Predictable' Toons

Sunday 'Totally Predictable' Toons Democracy STILL Our Best Way Out of This Mess -- And Repubs Know It: 'BradCast' 7/10/25

Democracy STILL Our Best Way Out of This Mess -- And Repubs Know It: 'BradCast' 7/10/25 'Green News Report' 7/10/25

'Green News Report' 7/10/25

'Mass Shooter Subsidy'?: More Dumb, Deadly Stuff in Trump's New Law: 'BradCast' 7/9/25

'Mass Shooter Subsidy'?: More Dumb, Deadly Stuff in Trump's New Law: 'BradCast' 7/9/25  Trump's New Law Supersizes ICE, Mass Detention, Militarization: 'BradCast' 7/8/25

Trump's New Law Supersizes ICE, Mass Detention, Militarization: 'BradCast' 7/8/25  'Green News Report' 7/8/25

'Green News Report' 7/8/25 Texas Flooding Tragedy Was Both Predictable and Predicted: 'BradCast' 7/7/25

Texas Flooding Tragedy Was Both Predictable and Predicted: 'BradCast' 7/7/25 Sunday 'Big Billionaire Bonanza' Toons

Sunday 'Big Billionaire Bonanza' Toons Sunday 'Total Obliteration' Toons

Sunday 'Total Obliteration' Toons 'Green News Report' 6/26/25

'Green News Report' 6/26/25 Thank You For Your Attention to This Matter:

Thank You For Your Attention to This Matter: Mamdani Primary 'Win' Augurs New Era of Rising Progressives: 'BradCast' 6/25/25

Mamdani Primary 'Win' Augurs New Era of Rising Progressives: 'BradCast' 6/25/25 U.S. Authoritarianism Under-way (But We're Still Here to Fight It): 'BradCast' 6/24/25

U.S. Authoritarianism Under-way (But We're Still Here to Fight It): 'BradCast' 6/24/25 'Anti-War' Trump Attacks Iran on False Claims About WMD: 'BradCast' 6/23/25

'Anti-War' Trump Attacks Iran on False Claims About WMD: 'BradCast' 6/23/25 Senate Health Care Cuts 'More Extreme' Than House Version: 'BradCast' 6/19/25

Senate Health Care Cuts 'More Extreme' Than House Version: 'BradCast' 6/19/25 What 'Anti-War President'? MAGA Civil War Over Trump, Iran: 'BradCast' 6/18/25

What 'Anti-War President'? MAGA Civil War Over Trump, Iran: 'BradCast' 6/18/25 Trump's 'Remigration' is Code for 'Ethnic Cleansing': 'BradCast' 6/17/25

Trump's 'Remigration' is Code for 'Ethnic Cleansing': 'BradCast' 6/17/25 Last Weekend Today: 'BradCast' 6/16/25

Last Weekend Today: 'BradCast' 6/16/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL