So long as there is a prospect for the issuance of a pardon by a Vice President once he/she becomes President, or the expiration of the statute of limitations while a President remains in office, the indictment of a sitting President may be the "only" constitutional means for ensuring "Equal Justice Under Law".

So long as there is a prospect for the issuance of a pardon by a Vice President once he/she becomes President, or the expiration of the statute of limitations while a President remains in office, the indictment of a sitting President may be the "only" constitutional means for ensuring "Equal Justice Under Law".

That conclusion, of course, is at odds with the official U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) position that a sitting President cannot be indicted until after he/she leaves office. The DoJ's position is based upon the December 10, 2000 Opinion issued by the DoJ's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), citing an earlier OLC opinion that "the institution of criminal proceedings 'would interfere with the President's unique official duties, most of which cannot be performed by anyone else.'"

But that position is flawed and is being challenged by a number of legal scholars, including Harvard Law Professor Laurence Tribe, a preeminent constitutional expert, whose famous former students include Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts and President Barack Obama.

In a December 10 Boston Globe op-ed and during a subsequent appearance on MSNBC's Last Word with Lawrence O'Donnell (see video below), Tribe noted that the long-controversial OLC opinion lacks the force of a judicial precedent and is at odds with the legal accountability required of all federal officers, including the President...

Constitution does not provide for in-office Presidential immunity

At first blush, one might think that the OLC's position that a President cannot be indicted until after he/she leaves office is supported by the Impeachment Clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

Article 1, Section 3, Clause 7 (aka the Impeachment Judgment Clause) provides:

However, the OLC concedes that an in-office Presidential immunity cannot be derived from the Impeachment Judgment Clause, in part, because that same Clause, per Article 2, Section 4, also applies to the "Vice President and all Civil Officers."

In its 2000 memo, the OLC cites and reaffirms the reasoning set forth in an Oct. 5, 1973 brief filed by Solicitor General Robert Bork and in a Sept. 24, 1973 memo issued by the Elliot Richardson-led Justice Department's OLC.

The Saturday Night Massacre took place on Oct. 20, 1973 --- less than one month after the issuance of the 1973 OLC memo. After Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus chose to resign rather than carry out Nixon's order to fire Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, Bork complied with Nixon's order to dismiss Cox.

In his brief, Bork argued against Spiro Agnew's claim that a Vice President could not be indicted unless and until the VP were impeached and removed from office. In its 1973 memo, the OLC "concluded that the plain terms of the [Impeachment Judgment] Clause do not impose...a general bar to indictment or criminal trial prior to impeachment and therefore do not, by themselves, preclude the criminal prosecution of a sitting President." In fact, as the OLC conceded, the word "nevertheless" in the Impeachment Judgment Clause was "intended...to signify only that prior conviction in the Senate would not constitute a bar to a subsequent prosecution."

In his 1973 brief, Bork also conceded that, with the exception of the Constitution's Speech or Debate Clause, which expressly confers immunity upon members of Congress from arrest or interrogation for any speech or debate entered during a legislative session, "the Constitution confers no explicit immunity from criminal sanctions for any federal officer."

Yet, Bork and the OLC argued in 1973 that "the indictment or criminal prosecution of a sitting President would impermissibly undermine the capacity of the executive branch to perform its constitutionally assigned functions." Specifically, the 1973 OLC memo contended that the institution of criminal proceedings "would interfere with the President's unique official duties, most of which cannot be performed by anyone else."

But the OLC failed to consider Section 3 of the 25th Amendment, adopted in 1967, which authorizes the President to temporarily delegate his or her duties to the Vice President by submitting a "written declaration" to the President Pro Tempore of the Senate and Speaker of the House, stating "that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office." In such a case, the VP becomes the Acting President. If a President were to be acquitted, he/she could restore his position as President by "transmitting a written declaration to the contrary."

In email remarks to The BRAD BLOG, Tribe underscored the "significant tension" between the OLC's opinion and the 25th Amendment "that the OLC ought to have considered but didn't take into account."

Longtime campaign finance and governmental ethics expert Craig Holman of Public Citizen echoed Tribe's scholarly view. Citing remarks from Nixon's one-time White House Counsel John Dean at a recent governmental ethics conference in Philadelphia, Holman explained that the issue has been "a matter of debate for decades," including during Nixon's legally contentious term in office. The notion that the Constitution bars the indictment of a sitting President, Holman said, "doesn't really hold water".

"The OLC opinion depends entirely on the notion that if you indict the President, you incapacitate the President," Holman told Brad Friedman during a recent BradCast interview. "Dean explained we've got the 25th Amendment in the Constitution. That sets up an entire transition period if the President becomes incapacitated. Then the Vice President takes over. So, there is no incapacitation. We know the transition. So, the President should be subject to indictment."

Moreover, in Tribe's view, the burden imposed on a President by a criminal proceeding is likely to be no greater than the burden of having to defend his or her office in a Senate impeachment trial, during which the President, absent invocation of the 25th Amendment, continues to retain all Executive Branch and Commander-in-Chief authorities.

To that, one might add that the OLC's exclusive concern about the adverse impact upon Executive Branch prerogatives ignores how in-office Presidential immunity interferes with the co-equal function of the federal government's Judicial Branch. As the U.S. Supreme Court observed in United States v. Nixon (1974), a criminal prosecution "is a judicial proceeding in a federal court alleging violations of federal laws and is brought in the name of the United States as sovereign." (Emphasis added).

Framers did not envision Presidential impunity

The text of the Impeachment Judgment Clause reveals that the framers assumed that, ordinarily, impeachment would precede criminal proceedings. It also reveals, however, that the framers presumed that a President would subsequently be subject to a criminal indictment and trial. Specifically, Article I, Section 3 states that an impeached President "shall" be "liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law." (See also, The Federalist Papers No.69, in which Alexander Hamilton observed that "afterword" an impeached President who had been convicted and removed from office would "be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law").

There is nothing in the text or history of the U.S. Constitution, written in 1787, that suggests the framers had so much as remotely considered the possibility that a delay in the initiation of criminal proceedings would effectively permit a President to commit crimes with impunity, knowing that he/she could never be prosecuted so long as, following impeachment and removal from office, his/her hand-picked successor would issue a Presidential pardon.

Presidents and Vice Presidents did not run together as part of a single ticket until 1804. President Gerald Ford's then unprecedented 1974 decision to pardon President Richard Nixon, after the latter resigned rather than face certain impeachment, was so controversial and unexpected that Ford's White House Press Secretary resigned in protest. A Newsweek White House correspondent said, at the time, that "no one could believe it."

The advent of Ford-like pardons is not the only factor that weighs against Presidential in-office immunity.

Over the past two years, a Republican-controlled Congress has refused to so much as perform its oversight functions, let alone initiate serious inquiry designed to establish whether President Donald J. Trump has committed impeachable offenses. Instead, House Republicans openly sought to defend Trump by aiding his spurious attacks on the FBI, the DoJ and the Special Counsel investigation. According to CNN, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes (R-CA) "told donors that the Republican majority in the House has been and remains the main firewall that has protected President Donald Trump from the fallout that could come from special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation".

The 2018 midterm's "Blue Wave" produced a Democratic majority in the House and opened the door to legitimate inquiry that could potentially produce compelling evidence of the President's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. But, there's an open question as to how many Republican Senators would be of the same mind as Nixon-partisan, Rep. Earl Langrebe (R-IN), who, when confronted with the "smoking gun" Oval Office audiotapes in 1974, infamously replied: "Don't confuse me with the facts. I've got a closed mind."

While impeachment has always entailed political as well as legal questions, it is unlikely that, in 1787, the framers foresaw the possibility that so many members of Congress would place party loyalty ahead of their solemn oaths to support and defend the U.S. Constitution. To extend judicial immunity from criminal prosecution to a President who may have acquired office by fraud, deceit and the illegal assistance of a foreign power under circumstances where so many members of Congress refuse to take up impeachment --- facts be damned --- is to shred the very fabric of our constitutional Republic and the principle of "Equal Justice Under Law".

Legal maxims

There are two legal maxims that also weigh against immunizing President Trump from criminal prosecution while in office: (1) Fraud vitiates consent, and (2) no one should profit from their own wrong.

The first was embodied in this Laurence Tribe Tweet:

NEW RULE:

Cheat & lie & commit enough felonies to become president — and you’ll get not just the office with all its powers, but a permanent get-out-of-jail-free card!

Retweet if you doubt Madison and Hamilton were dumb enough to put that incentive scheme in place.

— Laurence Tribe (@tribelaw) December 13, 2018

The "consent" electors provided by a sufficient number of votes for Trump to acquire an Electoral College "victory" is arguably vitiated by the deceptions used to receive those votes.

Professor Tribe's op-ed analysis involved the second maxim. If the President were impeached and either resigned or was removed from office following conviction in the Senate only to be pardoned by Pence, Trump "would be free to return to private life, his riches perhaps enhanced in the interim by his use of the highest office in the land to receive unconstitutional emoluments from foreign powers."

Conclusion

The phrase, "constitutional crisis", has been frequently uttered but rarely appreciated.

The phrase, "constitutional crisis", has been frequently uttered but rarely appreciated.

The coupling of Congressional unwillingness to impeach a corrupt President with a misguided extension of criminal immunity for a sitting President poses a grave threat to the efficacy of the rule of law and to the very survival of constitutional democracy.

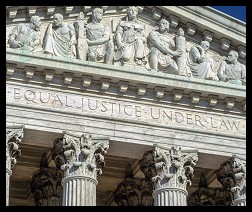

The concept of "Equal Justice Under Law" is so deeply embedded within the American system of jurisprudence that those words appear in all-CAPS above the entrance to the Supreme Court. It is a concept that will be obliterated if we allow for Presidential impunity.

If, as appears increasingly likely, the DoJ and Special Counsel Robert Mueller have amassed sufficient evidence to warrant it, both must seek Grand Jury indictments of Donald J. Trump while he is still in office.

Video of Prof. Tribe's appearance on MSNBC's Last Word with Lawrence O'Donnell follows...

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Kamala Rising:

Kamala Rising: Evidence Fails to Establish Attempted Trump Assass-ination Politically Motivated

Evidence Fails to Establish Attempted Trump Assass-ination Politically Motivated Former MAGA 'Cultist' on the State of the Race for 'MAGA Americans': 'BradCast' 7/23/24

Former MAGA 'Cultist' on the State of the Race for 'MAGA Americans': 'BradCast' 7/23/24  'Green News Report' 7/23/24

'Green News Report' 7/23/24

Biden Out, Endorses

Biden Out, Endorses BIDEN DROPS REELECTION BID

BIDEN DROPS REELECTION BID Sunday 'You Are Here' Toons

Sunday 'You Are Here' Toons What J.D. Vance Forgot to Tell You (and Lied About) at the RNC: 'BradCast' 7/18/24

What J.D. Vance Forgot to Tell You (and Lied About) at the RNC: 'BradCast' 7/18/24 'Green News Report' 7/18/24

'Green News Report' 7/18/24 Holding on for Dear Life Amid the Political Whirlwind: 'BradCast' 7/17/24

Holding on for Dear Life Amid the Political Whirlwind: 'BradCast' 7/17/24 Cannon's Corruption: 'BradCast' 7/16/24

Cannon's Corruption: 'BradCast' 7/16/24 'Green News Report' 7/16/24

'Green News Report' 7/16/24 Amid the Assassination Attempt Aftermath:

Amid the Assassination Attempt Aftermath:

Meanwhile... : 'BradCast' 7/11/24

Meanwhile... : 'BradCast' 7/11/24 'Green News Report' 7/11/24

'Green News Report' 7/11/24 Paging 'Johnny Unbeatable'! Dems (Actually!) in Disarray!: 'BradCast' 7/10/24

Paging 'Johnny Unbeatable'! Dems (Actually!) in Disarray!: 'BradCast' 7/10/24 SCOTUS Immunity Ruling 'As Bad as it Sounds', And Worse: 'BradCast' 7/9/24

SCOTUS Immunity Ruling 'As Bad as it Sounds', And Worse: 'BradCast' 7/9/24 So, What Now?: 'BradCast' 7/8/24

So, What Now?: 'BradCast' 7/8/24 Debunking MAGA Cult Xenophobia

Debunking MAGA Cult Xenophobia A Friendly Suggestion: Harris-Newsom 2024

A Friendly Suggestion: Harris-Newsom 2024 Prosecutor: SCOTUS Corruption Ruling Less Corrupt Than Appears: 'BradCast' 6/27/24

Prosecutor: SCOTUS Corruption Ruling Less Corrupt Than Appears: 'BradCast' 6/27/24 Good News and Bad: At the Polls and From the Corrupted Court: 'BradCast' 6/26/24

Good News and Bad: At the Polls and From the Corrupted Court: 'BradCast' 6/26/24 'Emptywheel' on Assange Hacking, Plea Deal: 'BradCast' 6/25/24

'Emptywheel' on Assange Hacking, Plea Deal: 'BradCast' 6/25/24

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL