On paper, Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., who was appointed by President Barack Obama to replace now Supreme Court Justice Elana Kagan as the U.S. Solicitor General, appears to be an experienced litigator with a distinguished background.

On paper, Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., who was appointed by President Barack Obama to replace now Supreme Court Justice Elana Kagan as the U.S. Solicitor General, appears to be an experienced litigator with a distinguished background.

It is a background that includes having served as a law clerk for former U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan, Jr. and having participated in over 100 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. However, Verrilli's participation in Supreme Court oral arguments --- earlier with respect to the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or "ObamaCare") and, recently, in the challenge to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, as well as U.S. v. Windsor, with respect to the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and in Hollingsworth v. Perry pertaining to California's Proposition 8 --- raises some disturbing questions.

Either Verrilli lacks the professional competence to assume primary responsibility for supervising and conducting litigation on behalf of the U.S. Government before the Supreme Court, or Verrilli, and the Obama administration, are so politically fearful of staking out principled positions that they have opted for a muddled middle ground. Perhaps it's a little of both.

Regardless, if the Windsor and Hollingsworth cases should establish a constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry, as urged by attorneys Ted Olson (R) and David Boies (D) in their Prop 8 Supreme Court brief [PDF], it will be despite the half-baked arguments presented by the Solicitor General, not because of them...

Previous Criticism

The Supreme Court, in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) upheld the constitutionality of almost all of the ACA, courtesy of a careful legal analysis of the Congressional power to tax that was set forth in the tightly crafted opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts.

It was a ruling that may have surprised many who had tuned into the Solicitor General's oral arguments, which CNN's legal analyst Jeffery Toobin described as "a train wreck for the Obama administration" and which Adam Serwer of Mother Jones labeled as "one of the most spectacular flameouts in the history of the court."

Where the Republican National Committee (RNC) unfairly seized upon Verrilli's nervous and awkward delivery to produce a heavily doctored audio ad to make the case that the ACA was "a tough sell," Jeff Rosen of The New Republic appropriately pointed to Verrilli's substantive deficiencies not only in his oral presentation but in his brief concerning the scope of Congressional power, even though those arguments had been presented by Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal (Rosen's brother-in-law) during the earlier Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeal proceedings and by states and several law professors before the Supreme Court.

His arguments meant to defend the crucial Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act recently were no better received, as highlighted in this Washington Post account of a reportedly exceedingly awkward exchange between the NAACP's President Benjamin Jealous and Verrilli himself not long after the hearing.

Muddled Middle Ground

One of the hallmarks of the Barack "lousy negotiator" Obama administration has been its proclivity to initiate negotiations by seeking out the most narrow position in the middle. When the tactic is employed in negotiations with Republicans, the only point to be determined is the extent to which the President will cave to right wing demands. When it occurs by way of legal arguments presented in a court of law, as occurred once again last week in both cases related to marriage equality, it simultaneously undercuts the government's core legal argument while suggesting that the administration lacks the courage of its convictions.

The differences between the principled position staked out by two of this nation's ablest appellate attorneys, Boies and Olson (the latter, formerly the Solicitor General for George W. Bush), in their Hollingsworth Supreme Court brief and the chiseling positions offered up in contrast by the Solicitor General were striking.

Relying primarily upon Loving v. Virginia (1967) the Supreme Court case which struck down Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage, Boies and Olson forcefully argued in their Hollingsworth Supreme Court brief that "the right to marry [is] one of the most fundamental rights --- if not the most fundamental right --- of an individual." It entails "the constitutional liberty to select the partner of one's choice," they argued persuasively, one that has never been conditioned upon the ability to procreate.

In urging the Court to extend the same strict scrutiny Equal Protection standards that it has historically applied to suspect classes, such as race, Boies and Olson pointed both to a solid factual record and the trial court's findings of fact that establish that "sexual orientation is 'immutable' or beyond the group members control;" that "gays and lesbians are 'a minority' that is 'politically powerless' to prevent discrimination by the majority," and that they have "been subjected to a history of pervasive and intolerable discrimination." The brief goes on to add that "it is equally clear...that an individual's sexual orientation bears no relationship to his or her ability to perform or contribute to society."

They not only argue that laws barring the right of same-sex marriage cannot withstand strict scrutiny --- which permits discriminatory legislation only where it is narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling governmental interest --- but argue that laws banning same-sex marriage do not meet even the far more permissive rational basis test.

Thus, Boies and Olson presented a broad, principled argument as to why same-sex marriage, like interracial marriage, should be regarded as a fundamental right guaranteed by the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the U.S. Constitution --- a position that need not be abandoned in order to advance a middle ground, as underscored by Olson during oral arguments...

MR. OLSON: Yes, the Ninth Circuit did that. You can decide the standing case that limits it to the decision of the district court here. You could decide it as the Ninth Circuit did.

Olson did not have to abandon principle by conceding the point because it was consistent with the basic legal principle, applied by the 9th Circuit in this case, that a court need not reach the broader issue, one which might apply to all states, "because California had already extended to committed same-sex couples both the incidents of marriage and the official designation of 'marriage,' and Proposition 8's only effect was to take away that important and legally significant designation, while leaving in place all of its incidents."

Verrilli, who joined with Olson and Boies in arguing for heightened scrutiny, undercut the efficacy and consistency of that argument by taking a middle ground approach in asserting that the government was arguing that an Equal Protection violation arises only in those states that already permit civil unions --- a muddled, middle ground that was scoffed at by both liberal and right-leaning Supreme Court Justices.

His argument suggested that states which currently allow "civil unions" for homosexuals might have to allow for same-sex marriage in order to meet the requirements of Equal Protection. But states that extend no recognition of gay couples at all would actually be rewarded by not needing to change anything, in the event that the court sides in favor of Equal Protection in both the Prop 8 and DOMA cases.

The liberal Justice Stephen Breyer seemed amazed in response to Verrilli's argument.

"Look, a State that does nothing for gay couples hurts them much more than a State that does something," Breyer said. "I mean, take a State that really does nothing whatsoever. They have no benefits, no nothing, no nothing. Okay? ... So a State that does nothing hurts them much more, and yet your brief seems to say it's more likely to be justified under the Constitution."

Liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was equally dumbfounded by the line of reasoning that Equal Protection only need be applied to states where civil unions already existed by law.

"General Verrilli, I could understand your argument if you were talking about the entire United States, but you — your brief says it's only eight or nine States, the States that permit civil unions," Ginsberg responded. "So a State that has made considerable progress has to go all the way, but at least the Government's position is, if it has done --- the State has done absolutely nothing at all, then it's --- it can do --- do as it will."

As if baiting a hook, right wing Justice Antonin Scalia returned to the issue.

"You are asking us to impose this on the whole country, not just California," he said to Verrilli, who subsequently took the bait.

"No, respectfully Justice Scalia, we are not. Our position is narrower than that. Our position --- the position we have taken, is about States, it applies to States that have, like California and perhaps other States, that have granted these rights short of marriage."

He then continued the same line in respones to Justice Roberts: "We are not --- we are not taking the position that it is required throughout the country. We think that that ought to be left open for a future adjudication in other States that don't have the situation California has."

In the DOMA case, the following day, the Solicitor General made a similarly weak case.

"What Section 3 [of DOMA] does," Verrilli argued in Windsor, "is exclude an array of Federal benefits to lawfully married couples. That means that the spouse of a soldier killed in the line of duty cannot receive the dignity and solace of an official notification of next of kin."

The example triggered this colloquy, this time with the right wing Justice Samuel Alito and then Scalia again:

GENERAL VERRILLI: The question in the case, Justice Alito, is whether Congress has a sufficiently persuasive justification for the exclusion that it has imposed...

JUSTICE ALITO:...Your...position seems to me, yes, one gets in, two stay out, even though your legal arguments would lead to the conclusion that they all should be treated the same.

GENERAL VERRILLI:...This is a different kind of a situation because the discrimination here is being visited on a group that has historically been subject to terrible discrimination on the basis of personal --

JUSTICE SCALIA: But that's — that's the same in the example that we just gave you, that discrimination would have been visited on the same group, and you say there it's okay.

GENERAL VERRILLI: No, I didn't say that. I said it would be subject to equal protection analysis certainly, and there might be a problem.

It boggles the mind how any experienced attorney --- much less the Solictor General of the United States --- would go to such lengths to evade the logical conclusion of his heightened scrutiny position as applied to all members of the LGBT community. It would have been an easy matter for Verrilli, in Windsor, to present the same basic position that Olson so consistently presented in Hollingsworth, to wit: Yes, Your Honor, the government takes the position that there would be an Equal Protection violation in all instances, but this Court need not reach that issue as this case entails a denial of benefits to someone who had taken part in a state-sanctioned, same-sex marriage.

Flip-Flopping on Federalism

In this instance, it would be charitable to describe the Solicitor General's performance during oral arguments on the DOMA case in Windsor as dismal!

Before I explain why, let's take a look at what was said.

GENERAL VERRILLI: We think that wouldn't raise an equal protection problem like this statute does, Mr. Chief Justice.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Well, no, my point is: It wouldn't — you don't think it would raise a federalism problem either, do you?

GENERAL VERRILLI: I don't think it would raise a federalism problem.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: You think Congress can use its powers to supersede the traditional authority and prerogative of the States to regulate marriage in all respects? Congress could have a uniform definition of marriage that includes age, consanguinity, etc., etc.?

GENERAL VERRILLI: No, I'm not saying that, Your Honor. I think if Congress passed such a statute, then we would have to consider how to defend it. But that's not --

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Well, but then there is a federalism interest at stake here, and I thought you told the Chief Justice there was not.

GENERAL VERRILLI: Well, with respect to Section 3 of DOMA, the problem is an equal protection problem from the point of view of the United States.

JUSTICE KAGAN: Yes, but, General, surely the question of what the Federal interests are and whether those Federal interests should take account of the historic State prerogatives in this area is relevant to the equal protection inquiry?

GENERAL VERRILLI: It's central to the inquiry, Justice Kagan. I completely agree with that point.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Oh, so it would be central to the inquiry if Congress went the other way, too?

It should be kept in mind that, prior to the Solicitor General's participation in the Windsor oral arguments, there was every indication that five of the Court's nine Justices were leaning towards the conclusion that, in confining the definition of marriage to a union between a man and a woman, Congress had unlawfully intruded upon the Federalism rights of those states which had recognized the validity of same-sex marriage.

For example, where attorney Paul D. Clement --- who was essentially representing the House GOP leadership --- argued that DOMA merely provided consistency with respect to who receives federal benefits, Justice Kennedy observed that DOMA applies to more than 1,100 Federal laws. That "means," Justice Kennedy added, "that the Federal Government is intertwined with the citizens' day-to-day life, you are at --- at real risk of running conflict with what has always been thought to be the essence of state police power, which is to regulate marriage, divorce, custody." To that, Justice Ginsberg added that, in passing DOMA, Congress "was really diminishing what the State said is marriage." DOMA creates "two kinds of marriage; the full marriage, and then this sort of skim milk marriage," she memorably offered.

Perhaps if Verrilli were not so singularly focused on his Equal Protection argument, he would have understood that federalism provided an alternative means for obtaining the result the Obama administration was seeking --- a Supreme Court determination that DOMA was unconstitutional. Instead, when Chief Justice Roberts baited his hook with a benevolent form of DOMA that included a federal recognition of same-sex marriage, the Solicitor General bit down so hard and then flipped back-and-forth over the federalism question so swiftly that he took on the appearance of a newly caught fish out-of-water.

The correct answer to the Chief Justice's question was that Congress could lawfully mandate that federal benefits be provided to all couples who are recognized as lawfully married under state law, including same-sex married couples, but Congress cannot dictate to any state whether or not they recognize same-sex marriage as lawful. States could only be compelled to recognize same-sex marriage as lawful if the Court ruled on the basis of the Constitutional Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment, as it did in Loving with respect to interracial marriage, that no state may deny the right to marry on the basis of sexual orientation.

The Solicitor General's initial concession that there would be "no federalism problem" was astoundingly stupid. Given the high level of official duties of the office of U.S. Solicitor General, the President would do well to ask Verrilli to step down. He should be replaced by someone of the same legal stature as his predecessor, Justice Elana Kagan.

If the Administration receives favorable rulings in either or both of these two cases, it will be, as was the case with "ObamaCare", despite the arguments presented by its own Solicitor General, not because of them.

Court Blocks Hegseth Censure of Sen. Mark Kelly

Court Blocks Hegseth Censure of Sen. Mark Kelly Harpy Tantrums, Legal Losses, Election Fails, Retreating ICE and Other Hopeful Signs: 'BradCast' 2/12/26

Harpy Tantrums, Legal Losses, Election Fails, Retreating ICE and Other Hopeful Signs: 'BradCast' 2/12/26 'Green News Report' 2/12/26

'Green News Report' 2/12/26

'Let Kids with Asthma Suffer': Trump to Reverse EPA's Landmark 'Endangerment Finding': 'BradCast' 2/11/26

'Let Kids with Asthma Suffer': Trump to Reverse EPA's Landmark 'Endangerment Finding': 'BradCast' 2/11/26 Trump's Presidency Now About Little More Than Racism, Corruption, Culture War Nonsense: 'BradCast' 2/10/26

Trump's Presidency Now About Little More Than Racism, Corruption, Culture War Nonsense: 'BradCast' 2/10/26 'Green News Report' 2/10/26

'Green News Report' 2/10/26 About Trump's FBI Raid of the Fulton County, GA Elections Warehouse: 'BradCast' 2/9/26

About Trump's FBI Raid of the Fulton County, GA Elections Warehouse: 'BradCast' 2/9/26 Sunday 'Dead in Darkness' Toons

Sunday 'Dead in Darkness' Toons 'New START' Treaty Allowed to End Amid New World Disorder: 'BradCast' 2/5/26

'New START' Treaty Allowed to End Amid New World Disorder: 'BradCast' 2/5/26 'Green News Report' 2/5/26

'Green News Report' 2/5/26 Trump Turns 'War on Terror' Tools Against Domestic Political Foes: 'BradCast' 2/4/26

Trump Turns 'War on Terror' Tools Against Domestic Political Foes: 'BradCast' 2/4/26 Losing Legally and Politically, Trump Threatens to 'Nationalize' Elections: 'BradCast' 2/3/26

Losing Legally and Politically, Trump Threatens to 'Nationalize' Elections: 'BradCast' 2/3/26 'Green News Report' 2/3/26

'Green News Report' 2/3/26 Bad and Good Bunnies, and an Electoral Shock in Deep 'Red' TX: 'BradCast' 2/2/26

Bad and Good Bunnies, and an Electoral Shock in Deep 'Red' TX: 'BradCast' 2/2/26 Sunday 'Mirror, Mirror' Toons

Sunday 'Mirror, Mirror' Toons 'Green News Report' 1/29/26

'Green News Report' 1/29/26 It's About Elections and the Windmills of His Mind: 'BradCast' 1/29/26

It's About Elections and the Windmills of His Mind: 'BradCast' 1/29/26 Govt Shutdown Over ICE Funding Near Certain This Weekend: 'BradCast' 1/28/26

Govt Shutdown Over ICE Funding Near Certain This Weekend: 'BradCast' 1/28/26 Trump Blinks, Bovino Out, MN Op Falters, Persists as Midterms Loom: 'BradCast' 1/27

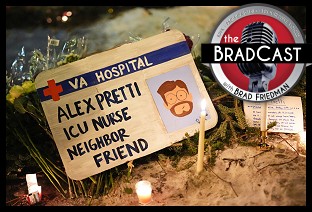

Trump Blinks, Bovino Out, MN Op Falters, Persists as Midterms Loom: 'BradCast' 1/27  The ICE Murder of ICU Nurse Alex Pretti and the Heroes of Mpls: 'BradCast' 1/26/26

The ICE Murder of ICU Nurse Alex Pretti and the Heroes of Mpls: 'BradCast' 1/26/26  The BRAD BLOG: 22 Years and Still Counting

The BRAD BLOG: 22 Years and Still Counting Mr. Smith Testifies (Publicly) in Washington: 'BradCast' 1/22/26

Mr. Smith Testifies (Publicly) in Washington: 'BradCast' 1/22/26 World Turning Against Self-Destructing U.S. Under Trump: 'BradCast' 1/21/26

World Turning Against Self-Destructing U.S. Under Trump: 'BradCast' 1/21/26 Trump Waste, Fraud, Abuse on Voting, at DOJ, by DOGE: 'BradCast' 1/20/26

Trump Waste, Fraud, Abuse on Voting, at DOJ, by DOGE: 'BradCast' 1/20/26

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL