[This article now cross-published by Salon...]

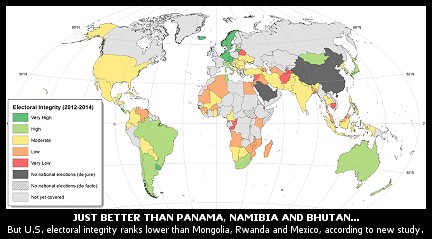

Electoral integrity has not improved in the U.S. over the past year, according to a new study. In fact, elections in Mexico now have more integrity than ours, the new survey, based on the observations of some 1,400 international election experts, finds.

Last year we reported: "A report [PDF] by researchers at Harvard and the University of Sydney finds the U.S. ranks just 26th on a global index of election integrity. That finding places the U.S. in the category of nations with 'Moderate' election integrity, ranking the country one notch above Mexico and one notch below Micronesia, according to the findings tracking elections in 66 countries."

Well, bad news --- of a sort. This year's new Electoral Integrity Project report [PDF] is now out. It takes into account the 2014 mid-term elections in the U.S. and more elections in a number of additional countries. It appears the U.S. has fallen a few pegs from it's 26th place ranking in last year's report [emphasis in the original]...

To make matters worse, the survey fails to examine the effects of vote-casting and counting technology on the integrity of elections. But, while the new report highlights what appears to be a huge drop in U.S. election integrity since last year's study, with our most recent national elections now ranked just worse than Mexico's and slightly better than those in Barbados, it's not all as bad as the plummeting ranking would seem to suggest...

Broader data this year

The Electoral Integrity Project's report is based on input from election experts worldwide, examining "all national parliamentary and presidential elections held in independent nation-states (with a population of more than 100,000)."

The previous report, the group's first, covered "73 national parliamentary and presidential contests held worldwide in 66 countries from 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2013."

The new one, however, surveys a larger number of countries and several more election cycles in them, covering "127 national parliamentary and presidential contests held worldwide in 107 countries from 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2014."

So with more countries (now 107, rather than 66) and more elections (now 127, rather than 73) graded by the experts, the overall rankings have changed a bit.

Where the 2012 U.S. Presidential election was rated in last years report as having only "moderate" integrity, by the study's benchmark, the 2014 Congressional elections in the U.S. slipped a bit lower.

"The number of elections has expanded," project leader Pippa Norris of Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government explained to The BRAD BLOG via email, "so it isn't clear whether there has actually been a fall. Better to say that the 2014 US midterms were ranked slightly lower than the 2012 presidential elections."

Each election cycle in each country is graded by the experts in the study. That input is placed into a 100-point index and then a comparative ranking based on 49 different indicators in 11 different stages of elections, such as Electoral Laws, Electoral Procedures, Voter Registration, Media Coverage, Campaign Finance and Voting Process.

The index is compiled in the survey into a "Perception of Electoral Integrity" (PEI) index. The 2012 Presidential election in the U.S. scored a 70.2 PEI. By that measure, it was ranked just just behind Micronesia's 2013 legislative election. The new score for the 2014 Congressional elections in the U.S. slipped to 69.3, one notch in the rankings ahead of Colombia and just behind both Barbados and Mexico.

Where the 2012 Presidential election ranked 26th overall in the previous report, that same election now ranks 42nd among the larger sample. Our Congressional election ranked 45th.

U.S. elections 'relatively poor'

According to the new report, the project's "concept of 'electoral integrity' refers to international standards and global norms governing the appropriate conduct of elections."

Some forty domestic and international experts were consulted about each election covered in the report, reflecting the views of 1,429 election experts.

The study finds "Elections in United States stand out as relatively poorly ranked by experts compared with other established democracies, deserving further scrutiny."

For similar reasons offered in last year's report, when the studies' experts rated the overall PEI of the 2012 Presidential election, "The November 2014 Congressional elections got poor grades because experts were concerned about the electoral laws, voter registration, the process of drawing district boundaries, as well as regulation of campaign finance."

The study cites U.S. voter registration, "in particular", as a concern. It cites new laws regarding access to the polls as "increasingly polarized and litigious...ever since the 2000 'Florida' debacle, generating growing controversy in state-houses and the courts."

"America also suffers from exceptionally partisan and decentralized arrangements for electoral administration," according to the study, which finds that recent Supreme Court decisions "suggest that the role of money in American politics deserves more detailed scrutiny."

What about the machines?

While the study examines a number of aspects during the "Vote Count" stage of elections, such as whether or not ballot boxes are "secure"; whether results are announced "without undue delay"; whether votes are "counted fairly"; and whether or not international and domestic election monitors are restricted, the survey fails to examine specific methods of vote casting and counting and the effect that may have on reported election results.

As The BRAD BLOG has spent more than ten years documenting, the method used for vote casting and counting --- and, with it, the electorate's ability to oversee the accuracy of the count --- this is no small matter. How votes are cast and tabulated can have an extraordinary effect (positively or negatively) on both the accuracy of elections as well as confidence in reported results.

Computerized voting systems --- such as Direct Recording Electronic (DRE, usually touch-screen) voting machines --- are 100% impossible to verify for accuracy after polls have closed. Yet, they are still used in about one-third of the country, and elsewhere around the world.

Hand-marked paper ballots can be examined after an election, but most jurisdictions in the U.S. tally those ballots by computerized optical-scan systems which either report results accurately or not. Without a human examination of those paper ballots --- only sometimes allowed in the rare event a recount --- it's impossible to know whether results have been accurately tallied and reported.

By way of just one recent example, which citizens happened to notice, a November 2014 referendum in a small Wisconsin town, tallied by a computerized optical-scan system last year, reported only 16 votes cast by some 5,350 voters. Luckily, the problem was so obvious, attributed to a programming error by a local election official, it was too ridiculous to be overlooked. The correct results were eventually determined by publicly hand-counting the hand-marked paper ballots.

But what of malfunction or malfeasance in vote counts that are not so easily discovered, thanks to a lack of human-verified results? For example, a computer optical-scan system in Palm Beach County, FL announced the "winners" of four different elections incorrectly in 2012. Only a sharp-eyed election official and an eventual court-sanction hand-count determined that three of four of the originally announced "winners" were actually the losers of their races. In New York's 2010 elections, thousands of ballots were inaccurately tallied by op-scan systems, though the failure was not publicly confirmed until 2012.

Those are just a few of the scores (if not hundreds) of similar reports we've covered over the years. And, of course, the accuracy of results from DRE systems can never be discovered at all. Jurisdictions that use them should clearly have their rankings penalized by the Election Integrity Project, whose report is subtitled "Why elections fail and what we can do about it". But so should jurisdictions which do not verify results or allow citizens to do so themselves. Additionally, the effect that such systems have on overall confidence in the results of elections, and subsequent interest by citizens in participating in them, should not be overlooked.

On this point, Harvard's Norris explained to us that their study is "technology neutral" and does not factor in such elements. "We don't ask questions about specific types of technologies, in part because this varies from place to place," she said.

While she correctly notes that "many countries don't use electronic technologies in balloting," she did not seem particularly receptive to the point that the way in which votes are cast and tabulated (and whether that count can be overseen by the public and known to be accurate) is a key aspect of electoral integrity. Her responses confirmed that those elements are only cursorily analyzed in the report by the very generalized questions regarding whether "Ballot boxes were secure" and if "Votes were counted fairly", and, perhaps, the question regarding whether "election monitors were restricted". (Naturally, if those monitors are unable to see inside a computer as to whether a vote is tabulated accurately, that would seem to be a very severe "restriction" on monitoring the most important point of the process.)

"There is no reason to assume a priori that vote counts using electronic or paper ballots are necessarily more honest or accurate," she says. That's a point we would vigorously dispute, even if only in the perception of accuracy, and the negative effect that unverified tallies have on confidence in elections and, thus, election integrity itself.

Norris adds: "The expert survey is only one component of the larger project and data collection. For example, we have another related project looking at public opinion towards electoral integrity."

The Electoral Integrity Project is relatively young. The broader scope of data analyzed in this year's new report is helpful, even as it shakes up previous rankings a bit. That's not unexpected as the breadth of their work matures. But, while offering a valuable comparative analysis of the integrity of various world democracies certainly provides a helpful yardstick --- and hopefully encourage countries to improve their own standings --- inclusion of the net effects of the type of vote-casting and counting systems used (along with the ability for the citizenry to oversee and verify results produced by them), would be a valuable and much-needed addition to their work.

(Snail mail support to "Brad Friedman, 7095 Hollywood Blvd., #594 Los Angeles, CA 90028" always welcome too!)

|

Hunter's Pardon:

Hunter's Pardon: Sunday 'First Things First' Toons

Sunday 'First Things First' Toons Sunday 'No Such Agreement' Toons

Sunday 'No Such Agreement' Toons How (and Why!) to 'Extend an Olive Branch' to MAGA Family Members Over the Holidays: 'BradCast' 11/21/24

How (and Why!) to 'Extend an Olive Branch' to MAGA Family Members Over the Holidays: 'BradCast' 11/21/24 'Green News Report' 11/21/24

'Green News Report' 11/21/24

Former Federal Prosecutor: Trump Must Be Sentenced in NY Before Taking Office Again: 'BradCast' 11/20/24

Former Federal Prosecutor: Trump Must Be Sentenced in NY Before Taking Office Again: 'BradCast' 11/20/24 'Bullet Ballot' Claims, Other Arguments for Hand-Counting 2024 Battleground Votes: 'BradCast' 11/19/24

'Bullet Ballot' Claims, Other Arguments for Hand-Counting 2024 Battleground Votes: 'BradCast' 11/19/24 'Green News Report' 11/19/24

'Green News Report' 11/19/24 Trump Already Violating Law (He Signed!) During Transition: 'BradCast' 11/18/24

Trump Already Violating Law (He Signed!) During Transition: 'BradCast' 11/18/24 Sunday 'Into the Gaetz of Hell' Toons

Sunday 'Into the Gaetz of Hell' Toons Computer Security Experts Ask Harris to Seek Hand-Counts Due to Voting System Breaches: 'BradCast' 11/14/24

Computer Security Experts Ask Harris to Seek Hand-Counts Due to Voting System Breaches: 'BradCast' 11/14/24 'Green News Report' 11/14/24

'Green News Report' 11/14/24 Trump Criminal Cases Fade, as GOP 'Does Not Believe in Rule of Law': 'BradCast' 11/13/24

Trump Criminal Cases Fade, as GOP 'Does Not Believe in Rule of Law': 'BradCast' 11/13/24 Climate Advocates Brace for Fight With Trump 2.0: 'BradCast' 11/12/24

Climate Advocates Brace for Fight With Trump 2.0: 'BradCast' 11/12/24 Let It All Out: 'BradCast' 11/11/24

Let It All Out: 'BradCast' 11/11/24 Not All Bad: Abortion Rights Won Big (Almost) Everywhere: 'BradCast' 11/7/24

Not All Bad: Abortion Rights Won Big (Almost) Everywhere: 'BradCast' 11/7/24 U.S. CHOOSES CONVICTED CRIMINAL, ADJUDICATED RAPIST: 'BradCast' 11/6/24

U.S. CHOOSES CONVICTED CRIMINAL, ADJUDICATED RAPIST: 'BradCast' 11/6/24 ELECTION DAY 2024: Tea Leaves, Probs for Voters, What's Next: 'BradCast' 11/5/24

ELECTION DAY 2024: Tea Leaves, Probs for Voters, What's Next: 'BradCast' 11/5/24 'Closing Arguments' for Undecideds, Third-Party Voters: 'BradCast' 11/4/24

'Closing Arguments' for Undecideds, Third-Party Voters: 'BradCast' 11/4/24 The GOP 'Voter Fraud' Before the Storm: 'BradCast' 10/31/24

The GOP 'Voter Fraud' Before the Storm: 'BradCast' 10/31/24

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL