I was watching a segment last night on Rachel Maddow's show with Desi Doyen, concerning the recent warnings issued to Americans and the evacuations at dozens of U.S. embassies and consulates in the Middle East and Northern Africa. The actions were taken due, we are told, to "chatter" detected by intelligence services of the possibility of attacks by al-Qaeda (and/or "associated forces") to American interests in the region.

I was watching a segment last night on Rachel Maddow's show with Desi Doyen, concerning the recent warnings issued to Americans and the evacuations at dozens of U.S. embassies and consulates in the Middle East and Northern Africa. The actions were taken due, we are told, to "chatter" detected by intelligence services of the possibility of attacks by al-Qaeda (and/or "associated forces") to American interests in the region.

Maddow framed the actions being taken by the U.S. government in the context of the infamous August 6, 2001 Presidential Daily Briefing memo --- "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US" --- ignored by George W. Bush just one month before the 9/11 attacks. Yesterday was the 12th anniversary of that memo.

In her conversation with NBC foreign affairs correspondent Andrea Mitchell, Maddow discussed the memory of that infamously ignored warning, and what effect it may have on the way the U.S. government now reacts to such detected threats. "In a post-9/11 world", the argument goes, President Obama and all future Presidents are likely to be very conscious of not underestimating such memos and "chatter," in the event that an attack does come about, for which they could later be held accountable for having ignored the "clear signs." (Not that George W. Bush or his administration was ever held accountable for such things, but that's a different matter.)

While watching the conversation about the dozens of closed diplomatic posts, I said to Desi, "I bet they're wildly over-reacting. It's not about post-9/11. It's about post-Benghazi."

In either an abundance or over-abundance of caution, U.S. embassies and consulates are being warned and shuttered and Americans are being air-lifted out of countries. It's not the memory of 9/11, at this point, that the government seems to be reacting to. It's as much the Republican reaction and/or over-reaction and/or political bludgeon made of the deaths of four U.S. personnel at our diplomatic outpost in Libya last year that seems to be leading to this reaction and/or over-reaction by the government.

Indeed, moments after I had uttered that thought to Desi, Mitchell said to Maddow: "I think, Rachel, that this is not just post-9/11, this is post-Benghazi."

The way our government now reacts to such events is not necessarily based on common sense, it seems to be as much based on fear. Not necessarily fear of being attacked, but fear of missing some important warning or another and then being held politically accountable for it later.

Since so much of this is kept secret --- except for stuff classified as "secret" and "top secret" that is routinely leaked by government officials who, unlike whistleblowers, are almost never held accountable for such leaks of classified information --- we are largely left to simply "trust" that the government is accurately portraying the threat, whether they are or not, and whether they are simply over-reacting out of caution and/or political ass-covering.

All of this, then, adds an interesting light to a curious story reported this week by Al-Jazeera English's Jason Leopold (formerly of Truthout) highlighting the government's seemingly bizarre claims that they have concerns that al-Qaeda may "attack the detention facilities at Guantanamo" or otherwise, somehow, "undermine security at the facility" if too much is known about what goes on there.

But that's not the most interesting aspect of the story...

Leopold, who has been closely covering events at the U.S. detention center in Guantanamo, has been filing a series of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests of late for documents concerning elements of that story, as well as a whole bunch of other national security issues.

Recently, as he describes in his report, he actually filed a motion to intervene [PDF] in a lawsuit filed on behalf on prisoners being held at Gitmo which contests the genital searches they are being subjected to before and after meetings with their attorneys.

Last month, Leopold reports, a federal judge ordered the searches stopped, finding them to be "religiously and culturally abhorrent." Attorneys for the prisoners have argued that the searches have made their clients less likely to meet with them, and that, not security, is the real reason for the invasive and unnecessary policy being enforced by the U.S. government.

The government is now appealing the court's decision to stop the policy. That decision has has been temporarily stayed as the appeal moves forward.

The motion filed by Leopold sought to unseal a June 3 declaration from Guantanamo's prison warden, Colonel John Bogdan, which, according to a brief filed by government lawyers in response [PDF] to the motion, offers details on "operational-security and force-protection procedures" that, if released to the public, "would better enable our enemies to attack the detention facilities at Guantanamo or undermine security at the facility."

The facility at Guantanamo, Cuba, built as part of a U.S. military base could be attacked by al-Qaeda? Really? The government is demanding that we simply trust them on that, and therefore, they can't release the information on why genital searches of prisoners are necessary.

As Leopold explains, "Journalists can intervene in court cases and argue for the release of certain materials on the grounds that the public has a right of access to judicial records."

The government's brief in reply to his motion cites recent attacks on detention facilities in the middle of Iraq, to support their concerns about fully unsealing the declaration from Guantanamo's warden...

"Those attacks killed 16 Iraqi guards and released hundreds of al-Qaeda prisoners. Of note, Ayman al-Zawahri, al-Qaeda's leader, identified the [Joint Task Force-Guantanamo] detention facilities as a target during a 22-minute video posted July 31, 2013, stating: 'The terror network will spare no effort to free prisoners held at the US military-run detention centre in Cuba.'"

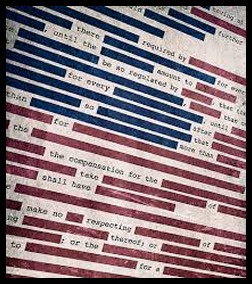

On Friday, writes Leopold, along with the government's brief, they "released a partially redacted version of Bogdan's declaration, and argued that the blacked-out passages in the document should remain secret --- because they contained sensitive 'operational-security information' about Guantanamo."

But here's the bizarre part. Leopold reports that...

Redacted passages that the government says needs to remain secret are unredacted in the earlier version filed on the public record as part of the government's appeal. At the same time, some unredacted passages in the declaration submitted on Friday are redacted in the public version of Bogdan's declaration filed with the appeals court last month.

You can take a look at Leopold's story to get an idea of the seemingly arbitrary differences between the two different government-redacted versions of the very same declaration --- the one that otherwise contains such sensitive material that, if it were released to the public, it would put the entire facility, somehow, at threat of attack by al-Qaeda.

Seeing the "sensitive" material redacted in one version of the document, as unredacted in the other, makes the government's claims seem even more absurd, at times. For example, in one passage, the declaration reads: "The frisk search that is conducted is to ensure there is nothing concealed between the clothing and the body." In the version of the same document submitted last month to the government, the word "frisk" is, for some reason, redacted.

"Most, if not all, of these decisions to withhold information are judgment calls, not simple questions of right or wrong," Steven Aftergood, Director of the Project on Government Secrecy told Leopold. "And depending on who does the redacting, you can often get a different result."

Aftergood says the two differently redacted versions of the very same document is "a great illustration of the subjective nature of the redaction process."

And, a great illustration of the subjective nature of our massive "secrecy state," to be frank.

Apparently, this is not all that unusual. Aftergood says that "One clever technique used by some [Freedom of Information Act] requesters is to request the same document from different agencies, because the agencies would de-classify it differently, and it was a good way to get more information released."

"The subjectivity of the classification process is important because it has implications for efforts to combat overclassification," Aftergood is quoted telling Al-Jazeera. "If decisions to classify information can be independently reviewed by other 'subjects' who have no self-interest in the classification decision, I think that kind of review process can help to strip away lots of unnecessary classification."

It is the fruits of that "unnecessary classification," the over-classification --- the massive secrecy state that has developed over the last decade or more, particularly since 9/11, which so many whistleblowers have been trying and trying to tell us about for so many years. The issue bumps up against so much that we are now trying to wrestle with as a nation.

That secrecy state is at the heart of the leaks by whistleblowers Manning and Snowden; the court proceedings and surveillance of journalists by the government; the necessary or unnecessary (who knows?) closure of diplomatic posts abroad; the refusal to respond to FOIA requests by the public; the efforts even by local and state governments to even keep citizens from overseeing the tabulation of ballots cast in their own public elections.

All of which underscores the subjective nature of the entire process and why independent oversight is so necessary, whether it's in regard to real Congressional oversight of our intelligence agencies; public oversight of Congress and of the secret rulings by the secret FISA court; or simply the ability of investigative journalists to carry out oversight of everything our government does (of, by and for the people, after all!).

I don't pretend to have the answer to this fine mess we've allowed ourselves to create --- largely out of fear, real, political, or otherwise --- but it needs to be highlighted and publicly discussed. Yes, there are legitimate reasons for some government secrecy. But, it seems, so much of the secrecy we have come to learn about of late is not necessary and not in service of us, we, the people, but rather of interests other than us --- whether those be corporate interests or the interests of government not being embarrassed for having fucked up.

It all needs to be discussed and considered, without fear. And we need a system of real oversight and checks and balances --- be it the Congress, the courts, the media, the citizens --- all of whom must be unafraid and unimpeded from uncovering and exposing government secrets and reporting them back to the public in the public interest. And the government, itself, needs to simply stop regarding virtually everything it does as a state secret.

As we've said many times over the years here, our Constitutional system of government is not built on "trust," it is supposed to be built on checks and balances and citizen oversight. That seems to be getting harder, not easier, and we, the people, need to figure out some way to unwind this ridiculous, unAmerican mess.

How (and Why!) to 'Extend an Olive Branch' to MAGA Family Members Over the Holidays: 'BradCast' 11/21/24

How (and Why!) to 'Extend an Olive Branch' to MAGA Family Members Over the Holidays: 'BradCast' 11/21/24 'Green News Report' 11/21/24

'Green News Report' 11/21/24

Former Federal Prosecutor: Trump Must Be Sentenced in NY Before Taking Office Again: 'BradCast' 11/20/24

Former Federal Prosecutor: Trump Must Be Sentenced in NY Before Taking Office Again: 'BradCast' 11/20/24 'Bullet Ballot' Claims, Other Arguments for Hand-Counting 2024 Battleground Votes: 'BradCast' 11/19/24

'Bullet Ballot' Claims, Other Arguments for Hand-Counting 2024 Battleground Votes: 'BradCast' 11/19/24 'Green News Report' 11/19/24

'Green News Report' 11/19/24 Trump Already Violating Law (He Signed!) During Transition: 'BradCast' 11/18/24

Trump Already Violating Law (He Signed!) During Transition: 'BradCast' 11/18/24 Sunday 'Into the Gaetz of Hell' Toons

Sunday 'Into the Gaetz of Hell' Toons Computer Security Experts Ask Harris to Seek Hand-Counts Due to Voting System Breaches: 'BradCast' 11/14/24

Computer Security Experts Ask Harris to Seek Hand-Counts Due to Voting System Breaches: 'BradCast' 11/14/24  'Green News Report' 11/14/24

'Green News Report' 11/14/24 Trump Criminal Cases Fade After Election as GOP 'Does Not Believe in Rule of Law': 'BradCast' 11/13/24

Trump Criminal Cases Fade After Election as GOP 'Does Not Believe in Rule of Law': 'BradCast' 11/13/24 Climate Advocates Brace for Fight With Trump 2.0: 'BradCast' 11/12/24

Climate Advocates Brace for Fight With Trump 2.0: 'BradCast' 11/12/24 'Green News Report' 11/12/24

'Green News Report' 11/12/24 Let It All Out: 'BradCast' 11/11/24

Let It All Out: 'BradCast' 11/11/24 Sunday 'Like it or Not' Toons

Sunday 'Like it or Not' Toons Not All Bad: Abortion Rights Won Big (Almost) Everywhere: 'BradCast' 11/7/24

Not All Bad: Abortion Rights Won Big (Almost) Everywhere: 'BradCast' 11/7/24 'Green News Report' 11/7/24

'Green News Report' 11/7/24 U.S. CHOOSES CONVICTED CRIMINAL, ADJUDICATED RAPIST: 'BradCast' 11/6/24

U.S. CHOOSES CONVICTED CRIMINAL, ADJUDICATED RAPIST: 'BradCast' 11/6/24 ELECTION DAY 2024: Tea Leaves, Probs for Voters, What's Next: 'BradCast' 11/5/24

ELECTION DAY 2024: Tea Leaves, Probs for Voters, What's Next: 'BradCast' 11/5/24 'Closing Arguments' for Undecideds, Third-Party Voters: 'BradCast' 11/4/24

'Closing Arguments' for Undecideds, Third-Party Voters: 'BradCast' 11/4/24 The GOP 'Voter Fraud' Before the Storm: 'BradCast' 10/31/24

The GOP 'Voter Fraud' Before the Storm: 'BradCast' 10/31/24 'Closing Arguments'with Digby and Driftglass: 'BradCast' 10/30/24

'Closing Arguments'with Digby and Driftglass: 'BradCast' 10/30/24 Trump Promises to be a Lawless, Authoritarian President. Believe Him: 'BradCast' 10/29/24

Trump Promises to be a Lawless, Authoritarian President. Believe Him: 'BradCast' 10/29/24 Ballots Burn, Billion-aires 'Obey in Advance', Callers Ring In: 'BradCast' 10/28/24

Ballots Burn, Billion-aires 'Obey in Advance', Callers Ring In: 'BradCast' 10/28/24 Musk's Privatized Internet Satellite System Threatens U.S. National Security

Musk's Privatized Internet Satellite System Threatens U.S. National Security

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL