In two separate federal lawsuits, Common Cause v Marion County Board of Elections (May 2, 2017) and Indiana NAACP v. Lawson (Aug. 9, 2017), both challenging restrictions on voting rights in Indiana, civil rights organizations have sought to block what they describe as unconstitutional Republican schemes that, with "surgical precision", seek to depress the vote in large minority, Democratic-leaning counties while contemporaneously enhancing voter turnout in white, Republican-leaning counties.

In two separate federal lawsuits, Common Cause v Marion County Board of Elections (May 2, 2017) and Indiana NAACP v. Lawson (Aug. 9, 2017), both challenging restrictions on voting rights in Indiana, civil rights organizations have sought to block what they describe as unconstitutional Republican schemes that, with "surgical precision", seek to depress the vote in large minority, Democratic-leaning counties while contemporaneously enhancing voter turnout in white, Republican-leaning counties.

The lawsuits entail two sets of laws. One of the lawsuits seeks to block a law that specifically targets Lake County --- and only Lake County --- for precinct consolidation and/or elimination. Lake County sports the state's second largest African-American population and its largest Hispanic population. The other lawsuit challenges a voter suppression scheme that significantly reduces early absentee voting sites for a significant number of African-American (Democratic) voters in Marion County, even while mostly white (Republican) voters in neighboring counties benefit from a significant expansion in the number of available early absentee voting sites.

Both sets of laws, as observed by Slate's Mark Joseph Stern, are part of the still-ongoing Republican response to the 2008 Presidential Election in which Barack Obama

That was a bridge too far for many Republican officials in the Hoosier State...

Early voting sites

Marion County, which includes the city of Indianapolis, has the highest percentage (28%) of African-Americans in Indiana. The Common Cause lawsuit seeks to enjoin the Indiana GOP's effort to significantly suppress the early absentee African-American Democratic vote in Marion County. Under a Marion County Board of Elections (MCEB) 2008 rule, registered voters in Marion County could cast early absentee ballots at one of three polling stations --- a central location and two satellite locations.

Marion County, which includes the city of Indianapolis, has the highest percentage (28%) of African-Americans in Indiana. The Common Cause lawsuit seeks to enjoin the Indiana GOP's effort to significantly suppress the early absentee African-American Democratic vote in Marion County. Under a Marion County Board of Elections (MCEB) 2008 rule, registered voters in Marion County could cast early absentee ballots at one of three polling stations --- a central location and two satellite locations.

Republicans on the MCEB eliminated the two satellite locations in 2010 and have repeatedly blocked their reinstatement. This meant that in 2016, there was but a single absentee early voting station for Marion County's nearly 700,000 registered voters. Just one early voting station per 699,709 registered voters in Marion County sharply contrasts with contiguous, and mostly White, Republican counties, who's election boards unanimously expanded the numbers of their early voting sites in 2016.

For example, in solidly Republican Johnson County (107,546 registered voters), election officials approved five (5) early voting sites, in addition to a site inside the office of the Circuit Court Clerk. Thus, during the 2016 election, Johnson County had one early voting site for every 17,924 registered voters --- as compared to just one for 699,709 voters in Marion County.

The result, as revealed by Fatima Hussein of IndyStar last week, was a 63% increase in White/Republican Hamilton County "in absentee voting from 2008 to 2016, while Marion County saw a 26% decline." Similar increases in early voting occurred in "Central Indiana Republican strongholds, including Boone, Johnson and Hendricks counties."

Where the elimination of two of the three early voting sites served to suppress Democratic Marion County turnout in the 2012 and 2016 elections, "voter turnout in each county contiguous to Marion County where satellite sites have been approved has steadily increased," according to the Common Cause complaint.

The issue stems also from a 2013 law that applied different rules to "counties with populations over 325,000", requiring that the adoption of additional early absentee voting sites receive unanimous approval by the county election board. That means that the single Republican on Marion's election commission has been able to block any expansion for its 700,000 voters. Only two of the state's 92 counties, Marion and Lake, had poulations larger than 325,000 when the state legislature adopted the bill in 2013.

In arguing that this disparate availability of early absentee voting in different Indiana counties violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the Common Cause complaint alleges that Indiana has maintained "an unequal system of early voting that unnecessarily and disproportionately burdens Marion County voters"...

Many Marion County voters, and especially those of color, also experience disadvantages in education, income, employment, and access to transportation, which when compounded by complications caused by childcare responsibilities and/or class schedules, makes it extremely difficult if not impossible for them to vote on Election Day. These disadvantages interact with other pre-existing election laws, including the earliest Election Day closing time in the nation (6:00 p.m.), the absence of an Indiana statute requiring employers to give employees time off to vote, and the absence of no-fault, mail-in absentee voting for able-bodied voters under the age of 65, to further exacerbate the burdens on Marion County voters by the arbitrary limitation of early in-person absentee voting to a single location.

Common Cause additionally alleges that this disparate system violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment and the Indiana Constitution, which guarantees that all elections be "free and equal."

The lawsuit seeks to establish at least two additional satellite early absentee voting locations for the 2018 election via an injunction that would prevent the MCEB from continuing to obstruct the creation of those satellite voting locations.

Consolidation/reduction of precincts

The NAACP lawsuit challenges a law, SB 220 (The Lake County Precinct Consolidation Law or LCPCL) , passed by the Republican super-majority in the state's General Assembly earlier this year. The law mandates the consolidation of "small precincts" (600 "active" voters or less). Curiously, this "consolidation" was purportedly passed as a cost savings measure, despite the fact that the "consolidation" had not been sought by Lake County. (The complaint alleges that the General Assembly usurped Lake County's right to determine what cost measures are appropriate.)

There are a total of 92 Indiana counties, including 24 other counties with "small precincts", yet the General Assembly arbitrarily singled out Lake County --- and only Lake County --- for precinct consolidation or elimination, according to the NAACP complaint.

Because of the definition of "small precinct," even within Lake County, the law has a disparate impact upon minority-majority cities --- Gary, East Chicago and Hammond --- which face consolidation or elimination of 83%, 70% and 81% of their existing precincts, respectively. This contrasts sharply with the 14 majority-White cities, towns, and unincorporated communities where only 41% of their existing precincts are at risk of consolidation or elimination of their existing precincts. "None of the approximately 1,345 precincts located in Indiana counties other than Lake County that contain under 600 active voters are at risk of consolidation or elimination," according to the NAACP complaint.

The NAACP complaint alleges disparate burdens that are quite similar to those in the Common Cause case.

The NAACP complaint goes on to allege that the LCPCL will increase costs, and that, by compressing large number of voters into fewer voting sites, the consolidation will enhance the prospect for long lines on Election Day.

These allegations are consistent with the conclusions set forth in a recent University of Florida research paper, prepared by three political science professors, who studied the impact of precinct consolidation/elimination in Manatee County, Florida.

The NAACP complaint goes on to note that the Lake County law fails to include funds for educating voters about the changes: "It is highly likely that a significant number of voters will be unaware that their precincts or polling locations have changed until they attempt to vote in 2018." Voters could "be turned away, or be forced to cast a provisional ballot that will not be counted because Indiana law mandates the rejection of any ballot cast by a voter in a precinct other than the one he or she is assigned."

The NAACP complaint alleges that the LCPCL violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, along with the 1st, 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution; that the law is arbitrary and fails to serve a valid governmental interest; that emergency and permanent injunctions should issue to prevent the State of Indiana from enforcing the law.

The legal arguments presented in both cases appear sound, but the cases will have to move swiftly if minority voting rights are to be protected as we approach the 2018 midterm election.

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

'Green News Report' 9/4/25

'Green News Report' 9/4/25

Trump's 'Cook'ed-Up Mortgage Fraud Claims: 'BradCast' 9/3/25

Trump's 'Cook'ed-Up Mortgage Fraud Claims: 'BradCast' 9/3/25  While We Were Out:

While We Were Out: 'Green News Report' 9/2/25

'Green News Report' 9/2/25 Sunday 'Shots and Prayers' Toons

Sunday 'Shots and Prayers' Toons Cynical Hypocrisy Behind Right-Wing Opposition To CA's 'Election Rigging Response Act'

Cynical Hypocrisy Behind Right-Wing Opposition To CA's 'Election Rigging Response Act' Sunday 'Random Acts of' Toons

Sunday 'Random Acts of' Toons From CA's 'Nuclear Deterrence' Map to Newsom's Trolling to Trump's 'Fascist Theatre' and Beyond: 'BradCast' 8/21/25

From CA's 'Nuclear Deterrence' Map to Newsom's Trolling to Trump's 'Fascist Theatre' and Beyond: 'BradCast' 8/21/25 'Green News Report' 8/21/25

'Green News Report' 8/21/25 'Americanism' and Trump's 'Stalinesque' Plot to Whitewash History: 'BradCast' 8/20/25

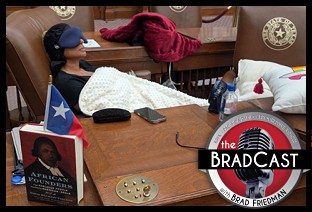

'Americanism' and Trump's 'Stalinesque' Plot to Whitewash History: 'BradCast' 8/20/25 Texas GOP Imprisons Dem State Lawmaker in State House Chamber: 'BradCast' 8/19/25

Texas GOP Imprisons Dem State Lawmaker in State House Chamber: 'BradCast' 8/19/25 'Green News Report' 8/19/25

'Green News Report' 8/19/25 Trump, Nazis and Trump's Nazified Elections: 'BradCast' 8/18/25

Trump, Nazis and Trump's Nazified Elections: 'BradCast' 8/18/25 Sunday '

Sunday ' Newsom's 'Election Rigging Response Act'; FCC's License Renewal for Sock-Puppeting Sinclair: 'BradCast' 8/14/25

Newsom's 'Election Rigging Response Act'; FCC's License Renewal for Sock-Puppeting Sinclair: 'BradCast' 8/14/25 'Green News Report' 8/14/25

'Green News Report' 8/14/25 140 New House Reps?: Moving Beyond the Gerrymandering Wars: 'BradCast' 8/13/25

140 New House Reps?: Moving Beyond the Gerrymandering Wars: 'BradCast' 8/13/25 FCC Renews Sinclair Licenses Despite Complaint from Petitioner Who Died

FCC Renews Sinclair Licenses Despite Complaint from Petitioner Who Died It's Not About the Rule of Law, It's About Authoritarian Control: 'BradCast' 8/12/25

It's Not About the Rule of Law, It's About Authoritarian Control: 'BradCast' 8/12/25 After Vaccine Cancels, CDC Shooting, Former Officials Want RFK Out: 'BradCast' 8/11/25

After Vaccine Cancels, CDC Shooting, Former Officials Want RFK Out: 'BradCast' 8/11/25 Trump Wars Against Greem Energy, Democracy on VRA's 60th: 'BradCast' 8/7

Trump Wars Against Greem Energy, Democracy on VRA's 60th: 'BradCast' 8/7 Media Conglomerates Continue Trump Capitulation: 'BradCast' 8/6/25

Media Conglomerates Continue Trump Capitulation: 'BradCast' 8/6/25 Banana Republican: Trump Shoots the Labor Statistics Messenger: 'BradCast' 8/5/25

Banana Republican: Trump Shoots the Labor Statistics Messenger: 'BradCast' 8/5/25 All's Fair in Love, War and, Apparently, Part-isan Gerrymandering: 'BradCast' 8/4/25

All's Fair in Love, War and, Apparently, Part-isan Gerrymandering: 'BradCast' 8/4/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL