Chalk up another blow to transparency and an informed electorate, and another judicial victory for the democratic perversion known as corporate "free speech."

Chalk up another blow to transparency and an informed electorate, and another judicial victory for the democratic perversion known as corporate "free speech."

Last week, in Minnesota Citizens for Life, Inc. v Swanson, six of the eleven jurists serving on the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeal struck down the provisions of a Minnesota statute requiring corporations which create separate political funds in excess of $100 to file periodic financial disclosure reports with the state.

The case had been filed by three corporations, all of which contended that the reporting requirements were so onerous as to amount to a de facto ban on corporate free speech that violated Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission [PDF]. That argument had been rejected first by a U.S. District Court Judge and then by way of a 2-1 Eighth Circuit panel decision. The majority on that panel had noted that even Citizens United recognized the government's right to "regulate corporate political speech through disclaimer and disclosure requirements" so long as the government did "not suppress that speech altogether."

On rehearing before the full 8th Circuit, Chief Judge William C. Reilly, a George W. Bush appointee, writing for the six member majority, acknowledged that the Minnesota statute "does not prohibit corporate speech." The majority ruled, however, that that state statute entailed excessive regulation which included an "ongoing" reporting requirement on the part of the corporate political fund that continues unless or until the corporation dissolves the fund. Chief Judge Reilly described that burden as both "onerous" and "monstrous."

The five dissenting jurists, which also included George W. Bush appointees, vigorously disagreed...

In a blistering dissent, Bush-appointed Circuit Judge Michael J. Melloy, accused the majority of giving "short shrift" to a second, fundamental principle enunciated by the Court in Citizens United --- the voting public's "right to know where the money is coming from."

Melloy, quoting from Citizens United, stressed that this principle applies not only to voters but to corporate shareholders:

Melloy described the majority's application of strict scrutiny "to a law that does not directly limit speech simply because the burdens the law imposes are heavy enough to be an indirect limit" as "circular and conclusory." He essentially accused the majority of judicial activism in failing to either recognize the state's legitimate interests in disclosure or to defer to the Minnesota legislature's right to determine reasonable reporting requirements.

According to Judge Melloy, the reporting requirements which Judge Reilly described as "onerous" and "monstrous" entailed the filing of "a single-page form and checking one box once in non-election years and five times in an election year."

The case could possibly wind up in the U.S. Supreme Court. But if it did, the result may be the same considering that the majority recently signaled, in shutting down a 100 year-old Montana anti-corruption statute, that they value corporate "free speech" in the form of an unlimited ability to fund commercial propaganda over a public right to know that is essential to democratic governance.

Ernest A. Canning has been an active member of the California state bar since 1977. Mr. Canning has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science as well as a juris doctor. He is also a Vietnam vet (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968). Follow him on Twitter: @Cann4ing.

A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25

A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25 'Green News Report' 10/30/25

'Green News Report' 10/30/25

Proposal for 'First Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29/25

Proposal for 'First Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29/25 Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections:

Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'Green News Report' 10/28/25

'Green News Report' 10/28/25 Let's Play 'Who Wants

Let's Play 'Who Wants Sunday 'Cartoonists Dilemma' Toons

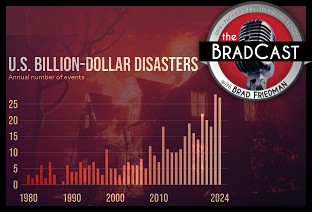

Sunday 'Cartoonists Dilemma' Toons Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25  'Green News Report' 10/23/25

'Green News Report' 10/23/25 Trump-Allied GOP Partisan Buys Dominion Voting Systems: 'BradCast' 10/22/25

Trump-Allied GOP Partisan Buys Dominion Voting Systems: 'BradCast' 10/22/25 Trump, Republican Law(lessness) & (Dis)Order: 'BradCast' 10/21/25

Trump, Republican Law(lessness) & (Dis)Order: 'BradCast' 10/21/25 'Green News Report' 10/21/25

'Green News Report' 10/21/25 Celebrating 'No Kings': 'BradCast' 10/20/25

Celebrating 'No Kings': 'BradCast' 10/20/25 Sunday 'How It Started' Toons

Sunday 'How It Started' Toons SCOTUS Repubs Appear Ready to Gut Rest of Voting Rights Act: 'BradCast' 10/16/25

SCOTUS Repubs Appear Ready to Gut Rest of Voting Rights Act: 'BradCast' 10/16/25 'Green News Report' 10/16/25

'Green News Report' 10/16/25 The 'Epstein Shutdown' and Other Autocratic Nightmares: 'BradCast' 10/15/25

The 'Epstein Shutdown' and Other Autocratic Nightmares: 'BradCast' 10/15/25 Group Vows to Block MO's GOP U.S. House Gerrymander: 'BradCast' 10/14/25

Group Vows to Block MO's GOP U.S. House Gerrymander: 'BradCast' 10/14/25 Trump Labor Dept. Warns Trump Policies Sparking Food Crisis: 'BradCast' 10/9/25

Trump Labor Dept. Warns Trump Policies Sparking Food Crisis: 'BradCast' 10/9/25 Trump's Losing Battles: 'BradCast' 10/8/25

Trump's Losing Battles: 'BradCast' 10/8/25 Trump, Roberts and His Stacked, Packed and Captured SCOTUS: 'BradCast' 10/7/25

Trump, Roberts and His Stacked, Packed and Captured SCOTUS: 'BradCast' 10/7/25 Trump Attempting His 'Invasion from Within': 'BradCast' 10/6/25

Trump Attempting His 'Invasion from Within': 'BradCast' 10/6/25 Biden Budget Expert: Mass Firings in Shutdown 'Illegal': 'BradCast' 10/2/25

Biden Budget Expert: Mass Firings in Shutdown 'Illegal': 'BradCast' 10/2/25 Why is DOJ Suing 'Blue' States for Their Voter Databases?: 'BradCast' 10/1/25

Why is DOJ Suing 'Blue' States for Their Voter Databases?: 'BradCast' 10/1/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL