"Obsessively?" Me? (He says as he writes this at 4:39am) Well, maybe. But someone's gotta.

So begins the editor's intro to a piece I was invited to submit to the Harvard University's Nieman Foundation for Journalism's Watchdog site. The invitation came from Deputy Editor, and Washington Post columnist Dan Froomkin, so I was honored to accept.

I was asked to submit questions for mainstream media folks to ask of Elections Officials about our current Electoral Train Wreck-in-Progress in hopes that someone in the MSM might actually do so. These are the tough questions which, frankly, ought to be asked of every damn Election Official in the country by every damn responsbile media person.

Several questions were edited out by Dan before posting for reasons that I don't completely understand. But as I consider him one of the good guys (who occassionally even links to BRAD BLOG from his WaPo page) I won't hold it against him.

So here's the piece as posted at Nieman Watchdog. (Including a swell pic of yours truly!)

And for the hard-cord Election Reform junkies, read on for the extra bonus questions which didn't make the cut. Who knows? Maybe someone in the MSM may one day want to know what they completely failed to ask about...

Q: The Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report on the "Security & Vulnerability of Electronic Voting" in September of 2005 which stated:

"[C]oncerns about electronic voting machines have been realized and have caused problems with recent elections, resulting in the loss and miscount of votes."

As well, the report also warned that ballots, definition files and audit logs could be easily modified, supervisor functions were easily accessed by malicious users, vendors frequently installed uncertified software on machines and multiple operational failures have occurred on almost all of the available systems. Have you read that non-partisan GAO report? If not, as an Election Official do you not feel a responsibility to do so as due diligence to ensure safe elections? And if so, what specific steps have you taken to mitigate the dangers about which the report warns?

Q: (For states and counties which use Diebold voting systems) Are you aware that a branch of the Dept. of Homeland Security issued a "Cyber Security Alert" in 2004 concerning an "undocumented backdoor" in Diebold's central tabulator software which, if accessed, could allow a malicious user to change the results of any election? Since Diebold still uses the same central tabulator software in their voting systems, what specifics steps have you taken to mitigate the risk warned of by the DHS?

Q: (For states and counties which use Diebold voting systems) Why do you feel voters should have confidence in your Diebold voting system --- either optical-scan or Direct Recording Electronic (DRE, touch-screen) --- when both systems have now been proven to be hackable via their memory cards in violation of the Federal Election Commission's Voting System Standards?

The FEC's Voting System Standards specifically ban "interpreted code" in the software of electronic voting systems. In February of 2006, Diebold admitted in a letter to California's Sec. of State, Bruce McPherson that they employ such code in both their optical-scan and touch-screen voting systems. "Interpreted code" is a danger because it allows a program to run differently depending on what information is given to it via the system's memory card at run-time. That security vulnerability, which was confirmed by an independent analysis commissioned by McPherson in January 2006, was used to flip a mock election on Diebold optical-scan voting equipment in Leon County, Florida in December of 2005.

McPherson's California analysis also found 16 other previously unknown bugs categorized as "more dangerous", "more serious" and going "well beyond" what was revealed in the Leon County hack.

Most elections officials will reply, when asked about this incredibly serious vulnerability with the information (or perhaps, misinformation) that's been given to them by Diebold. They will tell you that what happened in Leon County is the equivalent of leaving the safe door open in a bank and then being surprised when the money is gone the next day. They will tell you that the Leon County Election Director, Ion Sancho, who performed the mock election gave the passwords and keys to the system away, let the "hackers" hook their computers up to the system, and gave them access that nobody would ever have.

(The Election Director from the Arizona Secretary of State's office recently joined the many officials using that exact same misinformation when asked about the matter publicly.)

The fact of the matter is that Sancho, never gave away any passwords or keys to the system, and never allowed the "hackers" to plug their computers into the system in the now infamous "Hursti Hack" (so-named after Harri Hursti, the Finnish Computer Security Expert who devised and executed the hack.)

The "hackers" had changed information on a memory card, which they had obtained off the Internet for $100, and after the mock election there was no trace of their hack left behind?save for the paper ballots.

Both Sancho and the California analysis concluded that only a manual hand-count, or audit of a sufficient size, of those paper ballots (which is now illegal, by the way, in Florida and some other states) would have revealed the hack.

Protecting the chain of custody on the memory cards is the only recourse officials have come up with to try and ward off such an attack. However, since information on the memory card can be written to those cards, in a variety of ways, without ever removing them from the machine, there is really no safe way to use a Diebold machine which uses such code.

The only thing that officials can do is mitigate the threat via constant supervision of those cards and their chain of custody. Unfortunately, elections officials themselves often have regular access to the cards, as do poll workers who frequently store voting machines in their own houses in the days prior to an election. This is a very serious threat to the integrity of elections, no matter how trusted one feels their fellow election officials or poll workers may be.

Q: If there is a discrepancy discovered between the machine count and the paper count (or audit) which count will be the official one? Do you have rules in place before the election so such a decision won't have to be made afterwards if there is found to be such a discrepancy?

Stunningly, many election officials I have spoken with, even if they plan to recount ballots or "paper trails" after the election, have no procedure in place to determine which will be the official count in the event of a discrepancy. Waiting until after the election, when the problem is revealed, to determine such procedures is not acceptable and will lead to nothing but trouble.

There is no way to validate the count made by the software itself. So the only verifiable count is the paper, which must be the official "ballot of record" in such a dispute.

Sunday 'Random Acts of' Toons

Sunday 'Random Acts of' Toons From CA's 'Nuclear Deterrence' Map to Newsom's Trolling to Trump's 'Fascist Theatre' and Beyond: 'BradCast' 8/21/25

From CA's 'Nuclear Deterrence' Map to Newsom's Trolling to Trump's 'Fascist Theatre' and Beyond: 'BradCast' 8/21/25 'Green News Report' 8/21/25

'Green News Report' 8/21/25

On 'Americanism' and Trump's 'Stalinesque' Plot to Whitewash U.S. History: 'BradCast' 8/20/25

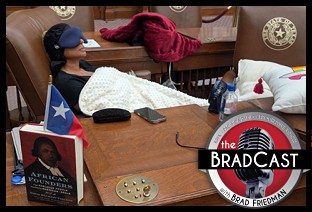

On 'Americanism' and Trump's 'Stalinesque' Plot to Whitewash U.S. History: 'BradCast' 8/20/25  Texas GOP Imprisons Dem State Lawmaker in State House Chamber: 'BradCast' 8/19/25

Texas GOP Imprisons Dem State Lawmaker in State House Chamber: 'BradCast' 8/19/25 'Green News Report' 8/19/25

'Green News Report' 8/19/25 Trump, Nazis and

Trump, Nazis and  Sunday '

Sunday ' Newsom's 'Election Rigging Response Act'; FCC's License Renewal for Sock-Puppeting Sinclair: 'BradCast' 8/14/25

Newsom's 'Election Rigging Response Act'; FCC's License Renewal for Sock-Puppeting Sinclair: 'BradCast' 8/14/25 'Green News Report' 8/14/25

'Green News Report' 8/14/25 140 New House Reps?: Moving Beyond the Gerrymandering Wars: 'BradCast' 8/13/25

140 New House Reps?: Moving Beyond the Gerrymandering Wars: 'BradCast' 8/13/25 FCC Renews Sinclair TV Licenses Despite Complaint from Petitioner Who Died Waiting

FCC Renews Sinclair TV Licenses Despite Complaint from Petitioner Who Died Waiting It's Not About the Rule of Law, It's About Authoritarian Control: 'BradCast' 8/12/25

It's Not About the Rule of Law, It's About Authoritarian Control: 'BradCast' 8/12/25 'Green News Report' 8/12/25

'Green News Report' 8/12/25 After Vaccine Cancels, CDC Shooting, Former Officials Want RFK Out: 'BradCast' 8/11/25

After Vaccine Cancels, CDC Shooting, Former Officials Want RFK Out: 'BradCast' 8/11/25 Sunday 'All's Well' Toons

Sunday 'All's Well' Toons 'Green News Report' 8/7/25

'Green News Report' 8/7/25 Trump Wars Against Greem Energy, Democracy on VRA's 60th: 'BradCast' 8/7

Trump Wars Against Greem Energy, Democracy on VRA's 60th: 'BradCast' 8/7 Media Conglomerates Continue Trump Capitulation: 'BradCast' 8/6/25

Media Conglomerates Continue Trump Capitulation: 'BradCast' 8/6/25 Banana Republican: Trump Shoots the Labor Statistics Messenger: 'BradCast' 8/5/25

Banana Republican: Trump Shoots the Labor Statistics Messenger: 'BradCast' 8/5/25 All's Fair in Love, War and, Apparently, Part-isan Gerrymandering: 'BradCast' 8/4/25

All's Fair in Love, War and, Apparently, Part-isan Gerrymandering: 'BradCast' 8/4/25 The Art of the Corrupt, Phony, Unlawful, Pretend Trade Deal: 'BradCast' 7/31/25

The Art of the Corrupt, Phony, Unlawful, Pretend Trade Deal: 'BradCast' 7/31/25 Battle Begins Against Trump EPA Climate Regulations 'Kill Shot': 'BradCast' 7/30/25

Battle Begins Against Trump EPA Climate Regulations 'Kill Shot': 'BradCast' 7/30/25 A Pu Pu Platter of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 7/29/25

A Pu Pu Platter of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 7/29/25 'Catastrophic' GOP Cuts to Medicaid, Medicare, ACA: 'BradCast' 7/28/25

'Catastrophic' GOP Cuts to Medicaid, Medicare, ACA: 'BradCast' 7/28/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL