Of all of the reactions to the July 16 joint press conference in Helsinki, Finland in which Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump responded to reporters' questions, perhaps the harshest assessment came in a Tweet by former CIA Director John Brennan.

Of all of the reactions to the July 16 joint press conference in Helsinki, Finland in which Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump responded to reporters' questions, perhaps the harshest assessment came in a Tweet by former CIA Director John Brennan.

Trump's "performance", Brennan contended, "rises to & exceeds the threshold of 'high crimes & misdemeanors.' It was nothing short of treasonous."

Brennan may have been uniquely positioned to offer that assessment since he was amongst the intelligence officials, who, on Jan. 6, 2017, showed President-Elect Trump emails and texts between high-level members of Russia's military intelligence agency, the GRU, that purportedly establish that Putin had personally ordered the cyberattack on the 2016 election.

Various half-hearted walk-backs aside, Trump's continued refusal to accept that Putin personally ordered Russia's alleged cyberattacks on the 2016 election and denial that any such attacks might have even taken place, is at odds with (a) the bipartisan conclusions offered by the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee; (c) an extraordinarily detailed, 37-page speaking indictment in February, setting forth how 13 Russians and 3 Russian companies allegedly carried out an illegal foreign influence campaign, and (d) the more recent, 29-page, July 13 indictment filed against 12 members of the GRU, laying out the dates and specific manner in which named individuals are said to have carried out cyberattacks on the DNC, Hillary Clinton's campaign chair and many others.

The July 13 indictment also details the manner in which Special Counsel investigators say emails --- purloined information --- from several of those attacks were weaponized for release during the campaign and that, for the first time, the GRU had targeted Clinton's "personal office" emails on the very same day that candidate Trump publicly called for Russia to find her "missing" emails during a July 27, 2016 campaign rally.

Ironically, as observed by MSNBC's Lawrence O'Donnell, Trump's decision to cast aside the unanimous conclusions of U.S. intelligence and law enforcement after the Helsinki summit was promptly followed by a "Perry Mason moment" when Putin was questioned by Reuters correspondent Jeff Mason at the joint press conference of the two Presidents:

Putin: "Yes, I did. Yes, I did."

Early-on, as we reported last February, after accepting an assignment to conduct a human-sourced intelligence investigation into Trump's ties to Russia, Christopher Steele, a former British MI-6 intelligence officer, informed Glenn Simpson of research firm Fusion GPS that he, Steele, had a professional responsibility to report his findings to the FBI. He explained his reasoning at the time. Steele believed he'd uncovered a "crime in progress" and that there was a chilling prospect that the man who might become the 45th President of the United States was and is a compromised Russian asset.

Hillary Clinton appeared to share Steele's concern. During a debate, she not only described Trump as "Putin's puppet," but also presciently added: "You encouraged espionage against our people, sign up for his wish list: break up NATO, do whatever he wants."

The very notion that a Commander-in-Chief could be a compromised foreign asset is so unprecedented that it is difficult to comprehend. Just think how history would have turned out if it had been George Washington instead of General Benedict Arnold who had committed treason.

Yet, the factors that suggest Trump is indeed compromised include, but are not limited to, (a) the retention of Michael Flynn for 18 days after Acting AG Sally Yates warned the White House that the DOJ believed Flynn was a compromised Russia asset, firing him only after Flynn was publicly exposed by the Washington Post; (b) the disclosure of highly classified information to Russia's ambassador during an Oval Office meeting; (c) the continuing refusal to impose Congressionally enacted sanctions against Russia --- a refusal that violates the President's duty to see that the laws are faithfully executed --- and (d) Trump's performance at and after the Helsinki Summit.

If Trump is, indeed, a compromised Russian asset, it would represent a monstrous betrayal, a clear and present danger to the national security of the United States and grounds for his removal from office. But, as Brad Friedman correctly observed during a July 16 BradCast, the question as to whether that betrayal amounts to "treason" entails a difficult, unsettled and far murkier legal issue as to whether the U.S. and Russia are at war...

No war, no treason

Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution is quite explicit. "Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort."

If, at the time of the Helsinki Summit, the U.S. and Russia were at war, then certainly President Trump's remarks could give rise to a charge of treason because he both adhered to our "enemy" and provided "aid and comfort" to that enemy.

The issue then is whether or not we are "at war" with Russia.

There are two questions: (1) when does a war begin? And (2) can a foreign cyberattack be considered an "act of war" against the United States?

Although Article 8, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution extends to Congress the exclusive power to "declare" war, in 1863, the U.S. Supreme Court, in The Prize Cases, upheld President Abraham Lincoln's unilateral order for the U.S. Navy to initiate a blockade of the nation's southern ports following the attack on Ft. Sumpter, even though that order preceded a formal Declaration of War. The Court ruled that the President was "bound to meet it in the shape it presented itself, without waiting for Congress to baptize it with a name."

No one seriously questions that the United States entered World War II the moment Japanese torpedoes and bombs began falling on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor on that "date which will live in infamy," December 7, 1941. Indeed, during his Dec. 8, 1941 Address to Congress, President Franklin D. Roosevelt expressly asked "that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire." (Emphasis added).

Congress adhered to this distinction when it passed the War Powers Resolution. Pursuant to 50 U.S.C., §1541 a President is authorized to introduce U.S. Armed Forces into hostilities pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.

Unlike Pearl Harbor and Ft. Sumpter, which entailed conventional attacks on U.S. military installations, we now deal with the issue of whether a foreign cyberattack is tantamount to an act of war.

In 2013, the Obama administration carried out what The New York Times described as a "secret legal review" which concluded that a President has the unilateral authority "to order a pre-emptive strike if the United States detects credible evidence of a major digital attack looming from abroad."

Although, as acknowledged in an analysis by constitutional law expert and professor Lyle Deniston, cyber warfare has the apparent "capacity to completely demobilize an entire nation's electronic communications network," the constitutionality of Obama's solicited legal opinion "cannot be analyzed or debated" so long as the legal rationale remains concealed.

In the current instance, we are not dealing with a President's authority to conduct pre-emptive cyber warfare, but instead, with the constitutional duty of a Commander-in-Chief to respond to ongoing Russian cyberattacks on the very core of our democratic institutions.

Limited warfare, measured response

It is perhaps somewhat difficult for citizens to wrap their heads around the concept that two nuclear powers, both of which possess the nuclear capability to destroy all life on this planet, can be at war with one-another without an immediate risk of Armageddon. That risk, however, does not negate the fact that the United States, and, most especially, the American electorate, according to the repeated assessments of the U.S. intelligence and law enforcement communities, have been victims of a targeted, multi-pronged Russian cyber warfare campaign.

For President Barack Obama, in his discretionary capacity as the Commander-in-Chief, he was faced with the dilemma of coming up with a measured response sufficient to deter further Russian cyber intrusions while minimizing the risk of harm to the United States from a Russian counter-measure.

According to the account provided by Michael Isikoff and David Corn in Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin's War on America and the Election of Donald Trump (2018), after then CIA Director Brennan informed Obama that Putin was overseeing the Russian cyberattack, two National Security Council analysts, Michael Daniel and Celeste Wallender, included, amongst the range of U.S. response options, a denial-of-service cyberattack on Russian news sites, a cyberattack designed to target Russia's troll farm, and a cyberattack threat to shut down Russia's entire civil infrastructure, which could cripple Russia's economy.

The two analysts were told to stand down. During a principals' meeting, according to Isikoff and Corn, James Clapper, then the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), opined that, in an infrastructure cyberwar the U.S. had more to lose, including a complete shutdown of the electrical grid.

On March 15, 2018, the United States Computer Emergency Response Team (US-CERT) published a joint tactical alert issued by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The Alert publicly revealed that, commencing no later than March 2016, Russian government cyber actors ("threat actors") began "targeting U.S. Government entities as well as organizations in the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors." This involved a "multi-stage intrusion campaign" in which the Russian threat actors "targeted small commercial facilities' networks where they staged malware, conducted spearphishing and gained remote access into energy sector networks."

Once access had been obtained, "the Russian government cyber actors conducted network reconnaissance, moved laterally, and collected information pertaining to industrial control systems," according to the Alert.

Thus, President Obama appears to have made the correct call when he chose not to launch a counter cyberattack against Russia's infrastructure. He chose instead to impose sanctions and expel Russian diplomats. But there was one area in which Obama failed to adequately perform his Commander-in-Chief duties. With or without the requested approval of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), which was sought, but not given, Obama could have minimized the impact of the Russian influence campaign by publicly revealing that we were under attack prior to the November 8, 2016 Presidential Election.

In his new book, Facts and Fears (2018), former DNI Clapper mused about his thoughts the day after Trump won the election:

Obama's failure to adequately notify the American people, that they were the target of a Russian cyberattack in time to mitigate the damages, deprived the American people of their right to make an "informed" electoral decision. It amounted to a judgmental error in terms of the exercise of his discretionary Commander-in-Chief powers. That was a far cry from what took place in Helsinki.

By adhering to the man who actually ordered the cyberattack on our democracy while simultaneously attacking the integrity of the U.S. intelligence and law enforcement communities, Donald J. Trump may very well have engaged in an act of treason --- one that warrants impeachment, removal from office, and, if a grand jury so determines, prosecution.

But that still depends on the unsettled question of what it means to be at war, and when such a war, if it exists, actually began.

Even if a jury subsequently found beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump committed treason, that conviction could be upheld only if our appellate courts, including the stolen Republican majority on the U.S. Supreme Court, concluded that the United States and Russia were, in fact, at war at the time the alleged "treason" occurred.

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

'Green News Report' 11/18/25

'Green News Report' 11/18/25

A Kaleidoscope of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 11/17/25

A Kaleidoscope of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 11/17/25  Sunday 'Back to Business' Toons

Sunday 'Back to Business' Toons Trump DOJ Takes Stand

Trump DOJ Takes Stand 'Green News Report' 11/13/25

'Green News Report' 11/13/25 Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Affordable' Afford-ability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12

Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Affordable' Afford-ability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12 After the Shutdown and Before the Next One: 'BradCast' 11/11/25

After the Shutdown and Before the Next One: 'BradCast' 11/11/25 'Green News Report' 11/11/25

'Green News Report' 11/11/25 Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25

Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25 Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons

Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons 'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25

'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25 'Green News Report' 11/6/25

'Green News Report' 11/6/25 BLUE WAVE! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25

BLUE WAVE! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25 Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25

Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25 Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25

Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25 A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25

A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25 Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29

Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29 Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25

Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25 Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25

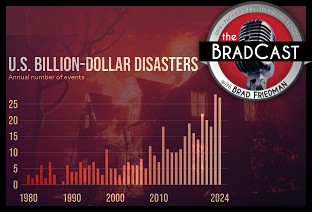

Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25 Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL