On November 8, every Californian who steps into a voting booth will face a momentous decision --- life or death?

On November 8, every Californian who steps into a voting booth will face a momentous decision --- life or death?

It is an awesome responsibility that cannot be avoided. To fail to cast a vote on one of the two competing death penalty ballot measures is to passively accept a California death penalty system that U.S. District Court Judge Cormac Carney aptly described as so "dysfunctional" and "irrational" in its application that it "serves no penological purpose" whatsoever.

Of the more than 900 human beings who have received death sentences in the Golden State since 1978, only thirteen (13) have been executed. During that time, California's death penalty system has operated at a cost of $5 billion or $384 million per execution. At present 748 men and women remain on death row, waiting to die.

The first of the two ballot measures, Prop 62, is backed by a wide array of political, educational, religious and civil liberties organizations. It is also supported by well-known politicians like California's Democratic Lt. Gov. Gavin Newson and former President Jimmy Carter. The measure is simple, direct and straightforward. A "yes" vote "repeals the death penalty and replaces it with life imprisonment without possibility of parole." Prop 62 would apply "retroactively to existing death sentences," and it would increase "the portion of a life inmate's wages that may be applied to victim restitution."

The second competing measure, Prop 66, the "Death Penalty Procedure Regulation" initiative, has been offered primarily by the same District Attorneys and law enforcement personnel who are currently responsible for the enforcement of the existing dysfunctional death penalty system. The object of Prop 66, they tell us, is to "mend not end" the death penalty system by severely curtailing the rights of the condemned both with respect the timing of direct appeals and subsequent collateral challenges by way of what are known as petitions for habeas corpus.

Where the death penalty repeal measure (Prop 62) can be readily understood by the average voter, the procedural changes reflected by Prop 66's wonky text are such that only those attorneys and judges who are actively engaged in death penalty appellate litigation can be expected to fully comprehend their true significance.

Prosecutors glibly assure voters that Prop 66 is a safe means to speed up the appeal process. Former DC public defender Stephen Cooper, on the other hand, describes Prop 66 as a "dubious," "arbitrary" and "macabre" proposal to turbo-charge "California's 'machinery of death'" --- a measure whose "cataclysmically-bad provisions" increase the ability of overzealous prosecutors to literally bury their mistakes...

Protecting the innocent

There is perhaps no graver mistake a state can make than to execute an innocent human being. Prosecutors assure voters that Prop 66 was "written to speed up the death penalty appeals system while ensuring that no innocent person is executed." Opponents, who can point to a list of 156 death row inmates nationwide who were first convicted and then exonerated, contend that "some have been executed because of poorly written laws like this one."

That list of exonerated death row inmates includes Henry Lee McCollum of North Carolina, who the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia believed deserved to be executed by lethal injection. In 2014 McCollum was exonerated after DNA evidence established his innocence.

In 2014 the Innocence Project presented a compelling case to the Texas Board of Pardons. Cameron Todd Willingham, they argued, had been wrongfully convicted for the arson murder of his two daughters. The conviction was not only based upon erroneous expert testimony that relied on "outdated arson science," but also upon what proved to be perjury on the part of a jailhouse snitch. Worse, the Innocence Project obtained a note from the District Attorney's own file that revealed the DA, who later became a judge, was himself guilty of suborning that perjury.

There was one significant difference between the McCollum and Willingham cases. The attorneys who represented McCollum were able to secure his release on the basis of the DNA evidence after he'd spent twelve years on death row. Willingham's attorneys, however, had pointed to the erroneous scientific evidence in seeking a stay of execution, but the DA, who at that time was concealing the perjury, successfully argued that the snitch testimony alone was sufficient to uphold the conviction. The note from the DA's file that exposed the perjury was presented in connection with a posthumous Innocent Project petition filed ten years after Willingham was executed.

The problem, of course, is much larger than just that one case. In a Golden Gate Univ. Law Review article, Loyola Law Professor Alexandra Natapoff observed that "45.9% of documented wrongful capital convictions have been traced to false informant testimony, making 'snitches the leading cause of wrongful convictions in U.S. capital cases'."

Californians should take little comfort in the fact that the wrongful convictions in the McCollum and Willingham cases occurred in other states. According to a U.C. Berkeley study, between 1989 and 2012, California led the nation in exonerations of wrongfully convicted citizens.

'Fool's Gold'

In his blistering analysis, Cooper, the former DC public defender, describes Prop 66 as "twenty-four carat fool's gold." Any effort to apply the changes retroactively to the 748 men and women now languishing on death row would, he asserts, engender "a long, bruising, legally dubious and extremely expensive fight." He reminds us that "we're not talking about curtailing an exploding population of coyotes"...

If Californians allowed that to happen, Cooper adds, they will have forfeited "their rightful seat at the table of civilized, just and peaceful people around the world --- whose countries long ago rejected capital punishment."

Neither a deterrent nor a source of closure

In arguing both against Prop 62 and in favor of Prop 66, prosecutors argue that the death penalty is needed to deter crime and afford closure for victims' families.

The first contention is dubious at best. According to a 2009 Northwestern University Law School study, an "overwhelming consensus among America’s top criminologists" reject the notion that the death penalty serves as a deterrent.

There's no solid evidence to support the proposition that the death penalty provides "closure" to victims' families. To the contrary, there's anecdotal evidence that the death penalty can divide families at a time when mutual support is most needed.

Right to competent appellate counsel

Cooper notes that under CA's existing system, the independent Habeas Corpus Resource Center is charged with the responsibility of providing timely, high-quality legal representation for indigent petitioners in death penalty habeas corpus proceedings. This accords with the guidelines of the American Bar Association (ABA) which provide that the selection of counsel should not be made by the judiciary. Prop 66 would place that responsibility in the hands of the CA Supreme Court.

The problem extends beyond who selects counsel. Prop 66 includes a provision that permits the CA Supreme Court to compel "attorneys who are qualified for appointment to the most serious non-capital appeals...to accept appointment in capital cases" --- something that could adversely impact the quality of representation when it is most needed.

Comparative costs

According to California's legislative analyst, the proposed repeal of the death penalty (Prop 62) would save California taxpayers "around $150 million annually." This contrasts sharply with Prop 66, which, during the near-term, is expected to potentially increase court costs in the tens of millions of dollars. That increased expense might be offset by tens of millions of dollars in annual savings for state prison expenses.

While costs should be considered, they should not be dispositive. If ever there was a moment in history in which a vote amounts to an act of conscience, this would be it.

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

'Green News Report' 4/1/25

'Green News Report' 4/1/25

Bad Court and Election News for Trump is Good News for America: 'BradCast' 3/31/25

Bad Court and Election News for Trump is Good News for America: 'BradCast' 3/31/25 Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons

Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons Vets Push Back at Trump, Musk Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25

Vets Push Back at Trump, Musk Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25 'Green News Report' 3/27/25

'Green News Report' 3/27/25 Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26

Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26 'Emptywheel' on Why Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace' After Signal Chat Debacle: 'BradCast' 3/25/25

'Emptywheel' on Why Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace' After Signal Chat Debacle: 'BradCast' 3/25/25 'Green News Report' 3/25/25

'Green News Report' 3/25/25 USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25

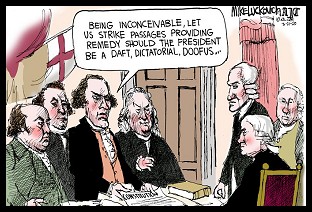

USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25 Sunday 'Suddenly Conceivable' Toons

Sunday 'Suddenly Conceivable' Toons 'Green News Report' 3/20/25

'Green News Report' 3/20/25 We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25

We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25 What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25

What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25 Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25

Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25 Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25

Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25 Trump EPA Unveils Plans to Endanger, Sicken Americans: 'BradCast' 3/13/25

Trump EPA Unveils Plans to Endanger, Sicken Americans: 'BradCast' 3/13/25 Trump Nixed Enforce-ment Against 100 Corp. Lawbreakers: 'BradCast' 3/12/25

Trump Nixed Enforce-ment Against 100 Corp. Lawbreakers: 'BradCast' 3/12/25 Bad Day for 'Strongmen': 'BradCast' 3/11

Bad Day for 'Strongmen': 'BradCast' 3/11 WI Election Could Flip Supreme Court Control, Musk Jumps In: 'BradCast' 3/10

WI Election Could Flip Supreme Court Control, Musk Jumps In: 'BradCast' 3/10

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL