Guest essay by Ernest A. Canning

Irrespective of whether one accepts the government's official explanation or one of the multiple "inside job/false-flag" theories advanced by the "9/11 Truth" movement, or even if you simply regard the current state of public information about 9/11 to be inadequate to arrive at any hard-and-fast conclusions about that seminal event, the mere mention of it evokes the word "terror" in some way for all Americans.

But the word "terror" is rarely applied to Donald Rumsfeld's "shock and awe" assaults on the city of Fallujah. Why?...

'Terrorism' and 'State Terrorism' defy definition

When Eqbal Ahmad said "The terrorist of yesterday becomes the hero of today, and the hero of yesterday becomes the terrorist of today," in his lecture, “Terrorism, Theirs and Ours,” he was referencing, among other issues, the transition of the Afghan Mujahideen, once described by President Reagan as the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers, into Osama Bin Laden’s al Qaeda, and the fact that Menachem Begin, at one time officially listed as a "terrorist" by the British, emerged as the Prime Minister of Israel.

As recognized by Wikipedia, the "politically and emotionally charged" word "terrorism" has no internationally agreed upon definition.

"Terrorism" is frequently applied by governments and by the corporate media to "guerrilla warfare," which is the traditional response of a weaker opponent who tactically seeks out soft targets rather than frontal military assault, e.g. the French Resistance fighters whom the Nazis referred to as "terrorists."

The concept of "state terrorism" is likewise controversial.

As noted by Michael Stohl, a terrorism scholar quoted by Wikipedia:

Perception of terror depends on point of view

9/11 was sudden; unexpected. Thanks to the immediacy of television, the images of planes striking buildings, jet fuel explosions, people leaping to their deaths, the collapse of the massive buildings, official confusion, and dust-covered civilians running for their lives, all of us were in a position to not merely see but experience the trauma.

That immediacy is nowhere to be found when we, a nation possessing the most powerful arsenal ever assembled, inflict terror on others.

There is a significant difference between how war is seen through the camera lens of a "smart bomb" and from the point of view of those upon whom the bombs are falling.

The deadly aerial assaults on Baghdad during Gulf War I and at the outset of the 2003 invasion of Iraq were depicted as surreal, florescent green over black light shows on CNN, Fox and MSNBC, who, acting as cheerleaders, did so over displays of "Countdown Iraq," "SHOWDOWN IRAQ," and "Target Iraq" plastered on their screens nonstop. But those images did not begin to display a brutal reality that is apparent only to those of us who have had the misfortune to serve in combat.

Viewed from a safe distance, even graphic images of war fail to reveal what Chris Hedges, in War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning, describes as the critical element --- fear:

State terror and Fallujah

In "This Is Our Guernica," independent journalist, Dahr Jamail, along with The Guardian's Jonathan Steele wrote:

In November 2004 the United States laid siege to the City of Fallujah, an Iraqi town about the size of Cincinnati --- the second such siege in seven months. The city was sealed off to relief workers and un-embedded reporters. While the American forces contend that a large insurgent force was trapped inside, a significant question exists as to whether most of the insurgents had fled the city in advance of the deadly assault --- an assault which Jamail contends resulted in the massacre of between 4,000 and 6,000 civilians.

Ali Fadhil, one of the first independent journalists permitted to enter the city some two months after the siege had ended, noted how shocked he was by the devastation:

Mr. Fadhil claimed that those killed were mostly civilians:

Dahr Jamail’s comparison of Fallujah to Guernica is both troubling and exceedingly poignant.

As Chalmers Johnson recounted in The Sorrows of Empire, “Guernica, a small Basque village in northern Spain, was the site Adolf Hitler [then allied with Francisco Franco] chose on April 27, 1937, to demonstrate his air force’s new high-explosive and incendiary bombs....The hamlet burned for three days, and sixteen hundred civilians were killed or wounded.”

The event’s modern significance is such that the United Nations prominently displays “a tapestry reproduction of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica,” a “depiction of the atrocity,” which Chalmers Johnson informs us, “is perhaps modern art’s most powerful anti-war statement” --- so powerful that the U.S. government took pains to cover the tapestry reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica with a large blue curtain in advance of the key pre-invasion address by then Secretary of State Collin Powell. Johnson notes that the “government decided...the carnage wrought by aerial bombing was an inappropriate backdrop for its secretary of state and its ambassador to the United Nations when they televised statements that might lead to the bombing of Iraqi cities.”

Prior to the first seige, in April 2004, Fallujah stood out as a symbol of the Iraqi resistance. It was the site where the four Blackwater mercenaries were killed and where their bodies were burned and left hanging on a bridge. Given the “shock and awe” mentality of the US military and especially Donald Rumsfeld, and considering the devastation that followed, there is every reason to believe that the US military and Rumsfeld had intended, by means of the two assaults on Fallujah, to apply such a deadly and massive display of force as to strike fear in the hearts of Iraqis everywhere: Resist and we will destroy you, your cities, your families.

The last thing a military bent on such a course would want is some independent, un-embedded journalist to, in the words of many Holocaust survivors, “bear witness;” to display the truth of the violent and bloody Fallujah assault for the entire world to see, especially since “collective punishment” and “the retributive destruction of cities in response to enemy actions” violate express provisions of the Geneva Convention.

Despite the best laid plans to seal off the city, a small team of brave journalists from al Jazeera, including correspondent Ahmed Mansur and cameraman Laith Mushtaq, found a way into the city where they remained, un-embedded for the duration of the first siege. On Feb. 22, 2006, the ghastly reality of the first Falluja seige was exposed as the two men discussed what they witnessed when interviewed on Democracy Now.

Mushtaq said:

Mushtaq spoke of a man named Hamudi, whose house had been bombed along with the entire neighborhood, “and they brought the corpses and bodies to the hospital,” where the scene was “like a sea of corpses...mostly children.... I was...forcing myself to take photographs, while I was at the same time crying.” Hamudi was the only survivor in his family. Mushtaq took pictures of Hamudi speaking to his infant son Ahmed, who was asleep with a toy car in his hand. “Half his head was gone.... I could not really find any one human being in one piece or intact.... It’s bombing of airplanes."

Mansur said:

Did Bush want to kill the messenger?

The April 9 and 10, 2004, images broadcast over al Jazeera for all the world to see did not sit well with the U.S. military’s media minders. On April 11, General Mark Kimmit, a senior military spokesman for the US forces in Iraq, said, “The stations that are showing Americans intentionally killing women and children are not legitimate news sources. That is propaganda, and that is lies.” According to Mansur, General Kimmit singled him out by name for criticism. An al Jazeera colleague, Hamoud Krishen, then asked General Kimmit, “Ahmed Mansur only transfers pictures. Do pictures themselves lie...?” General Kimmit did not respond.

On April 15, 2004, when asked by a reporter if he could “definitely say that hundreds of women and children and innocent civilians have not been killed,” Rumsfeld replied, “I can definitively say that what al Jazeera is doing is vicious, inaccurate and inexcusable.”

April 16, 2004, was the day of a Bush-Blair summit. On November 22, 2005, the London tabloid Daily Mirror exposed the existence of a five-page memo stamped “Top Secret” which had found its way to the offices of former Labor MP Tony Clarke. According to the Daily Mirror account, the memo reflects that during the summit --- a summit which took place one day after Rumsfeld’s “what al Jazeera is doing is vicious” diatribe --- President Bush “made clear that he wanted to bomb al Jazeera in Qatar and elsewhere” and that Prime Minister “Blair replied that would cause a big problem. There’s no doubt what Bush wanted to do --- and no doubt Blair didn’t want him to do it.”

The allegation, if true, merely underscores the length to which our leaders are prepared to go to insure that the truth remains concealed.

As Glenn Greenwald so aptly observed during his Dec. 31, 2009, appearance on Democracy Now, where we Americans assume we are better informed than Muslims whom we perceive as living in backward countries under the spell of religious fanaticism, the reverse is true. The people upon whom the bombs fall are well aware of the fact that "we routinely slaughter innocent men, women and children" --- a basic reality that almost never appears in the U.S. corporate-owned media, according to Greenwald, who added:

Peace depends on our understanding their point of view

If we are to put an end to what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., described as the "madness," the American public must, en masse, acquire the point of view of those upon whom the bombs are falling. For it is only by acquiring their point of view that Americans can appreciate and answer the poignant question posed by Greenwald and recounted by Brad Friedman as to the "why" growing numbers of Middle East residents just might be motivated to attack us. Without that understanding, peace will always remain beyond our grasp.

===

Ernest A. Canning has been an active member of the California state bar since 1977. Mr. Canning has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science as well as a juris doctor. He is also a Vietnam vet (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968).

It's About Elections and the Windmills of His Mind: 'BradCast' 1/29/26

It's About Elections and the Windmills of His Mind: 'BradCast' 1/29/26 'Green News Report' 1/29/26

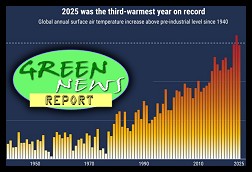

'Green News Report' 1/29/26

Govt Shutdown Over ICE Funding Near Certain This Weekend: 'BradCast' 1/28/26

Govt Shutdown Over ICE Funding Near Certain This Weekend: 'BradCast' 1/28/26 Trump Blinks, Bovino Out, MN Op Falters but Continues as Midterm Accountability Looms: 'BradCast' 1/27/26

Trump Blinks, Bovino Out, MN Op Falters but Continues as Midterm Accountability Looms: 'BradCast' 1/27/26 'Green News Report' 1/27/26

'Green News Report' 1/27/26 The ICE Murder of ICU Nurse Alex Pretti and the Heroes of Minneapolis: 'BradCast' 1/26/26

The ICE Murder of ICU Nurse Alex Pretti and the Heroes of Minneapolis: 'BradCast' 1/26/26  The BRAD BLOG: 22 Years and Still Counting

The BRAD BLOG: 22 Years and Still Counting Sunday 'Worth a Thousand Words' Toons

Sunday 'Worth a Thousand Words' Toons Mr. Smith Testifies (Publicly) in Washington: 'BradCast' 1/22/26

Mr. Smith Testifies (Publicly) in Washington: 'BradCast' 1/22/26 'Green News Report' 1/22/26

'Green News Report' 1/22/26 World Turning Against Self-Destructing U.S. Under Trump: 'BradCast' 1/21/26

World Turning Against Self-Destructing U.S. Under Trump: 'BradCast' 1/21/26 Trump Admin Waste, Fraud, Abuse on Voting, at DOJ, by DOGE: 'BradCast' 1/20/26

Trump Admin Waste, Fraud, Abuse on Voting, at DOJ, by DOGE: 'BradCast' 1/20/26 'Green News Report' 1/20/26

'Green News Report' 1/20/26 Sunday 'Domestic Terrorist' Toons

Sunday 'Domestic Terrorist' Toons 'Green News Report' 1/15/26

'Green News Report' 1/15/26 'A Cornered Rat': Trump Terrorizes Minneapolis, Menaces NATO, World: 'BradCast' 1/15/26

'A Cornered Rat': Trump Terrorizes Minneapolis, Menaces NATO, World: 'BradCast' 1/15/26 'Not Close to Over': Mad King Trump in Venezuela (& Beyond): 'BradCast' 1/14

'Not Close to Over': Mad King Trump in Venezuela (& Beyond): 'BradCast' 1/14 Things Getting Weirder as Trump Keeps Losing: 'BradCast' 1/13/26

Things Getting Weirder as Trump Keeps Losing: 'BradCast' 1/13/26 After ICE Murder in MN, Local Cops Disown Fed Policing Practices: 'BradCast' 1/12/26

After ICE Murder in MN, Local Cops Disown Fed Policing Practices: 'BradCast' 1/12/26 Trump to Congress, Climate, U.N., Rule of Law: DROP DEAD - 'BradCast' 1/8/26

Trump to Congress, Climate, U.N., Rule of Law: DROP DEAD - 'BradCast' 1/8/26 'Nonsense': Trumpers Claim 315k Fraudulent GA Votes in 2020: 'BradCast' 1/7/26

'Nonsense': Trumpers Claim 315k Fraudulent GA Votes in 2020: 'BradCast' 1/7/26 Jack Smith Testimony on Trump J6 Crimes, DOJ Weaponization: 'BradCast' 1/6/26

Jack Smith Testimony on Trump J6 Crimes, DOJ Weaponization: 'BradCast' 1/6/26 Trump War on Venez. is About Ego, Power, 'Alien Enemies Act': 'BradCast' 1/5/26

Trump War on Venez. is About Ego, Power, 'Alien Enemies Act': 'BradCast' 1/5/26

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL