I haven't been following this case at all, but I happened to be up very late last night when the cable news nets switched LIVE, around 2am out here, to carry the sentencing pronouncement for South Africa's Oscar Pistorius on the charge of "culpable homicide" (akin to manslaughter in the U.S.), for which he's been convicted in the 2013 killing of his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp.

I haven't been following this case at all, but I happened to be up very late last night when the cable news nets switched LIVE, around 2am out here, to carry the sentencing pronouncement for South Africa's Oscar Pistorius on the charge of "culpable homicide" (akin to manslaughter in the U.S.), for which he's been convicted in the 2013 killing of his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp.

The presiding judge for South Africa's High Court was Thokozile Masipa, an appointee of Nelson Mandela. She read her complete sentencing ruling aloud from the bench in the courtroom.

I was struck by one section that included several ideas that I don't recall hearing lately, if ever, in any sentencing for a criminal case of this sort in the U.S...

On the other hand, the latter might break the accused and the result might be just the opposite of what the punishment set out to do, which ultimately is to rehabilitate the accused, and to give him an opportunity, where possible, to become a useful member of society once more.

I have considered all of the evidence placed before me, and all the submissions and arguments by counsel. I have weighed all the relevant factors, the purposes of punishment and all forms of punishment, including restorative justice principles. I have also taken into account the seriousness of the offense which led to the death of the deceased, the personal circumstances of the accused and the interests of society. I have taken the particular circumstances of the accused at the time of the offense into account.

Having regard to the circumstances in the matter, I am of the view that a non-custodial sentence would send a wrong message to the community. On the other hand, a long sentence would not be appropriate either, as it would lack the element of mercy.

A sentence cannot be said to be appropriate without the feelings of mercy for the accused and hope for his reformation... I am mindful of the fact that true mercy has nothing to do with weakness or modeling sympathy for the criminal, but it is an element of justice.

...

The following is what I consider to be a sentence that is fair and just both to society and to the accused.

Pistorius was ultimately given a maximum 5-year prison sentence for his crime of culpable homicide, a lesser charge than either common murder or murder with direct intent, as defined in South African law. He also received a 3-year suspended sentence for related charges, to be served concurrently. The BBC reports that the double-amputee superstar sprinter could be freed from jail in as few as 10 months, but that Steenkamp's parents were "happy with the sentence and relieved the case was over."

As I said, I haven't been following the case closely, and from what I have heard, I don't find Pistorius' explanation for what happened to be particularly persuasive or even credible. Moreover, I don't know anything at all really about the South African justice system, so I don't have any particularly informed opinion on whether Pistorius' sentence is either fair or unfair, appropriate or inappropriate in this situation. None of that is the point of this post.

I was just simply struck by the concepts of "mercy", "rehabilitation", "reformation" and "restorative justice" being raised at all, as they were by the judge, in a case like this, and her point that punishment for such crimes --- at least in South Africa --- is not mean to "break the accused", but to help to rehabilitate them.

Those concepts of crime and punishment now seem about as foreign, absent and miles away from our modern day system of justice in the United States as...well, South Africa.

'Green News Report' 4/8/25

'Green News Report' 4/8/25

Cliff Diving with Donald: 'BradCast' 4/7/25

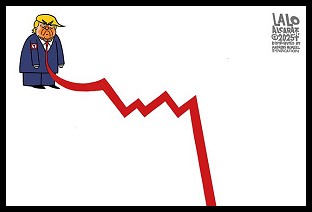

Cliff Diving with Donald: 'BradCast' 4/7/25 Sunday 'Don't Look Down' Toons

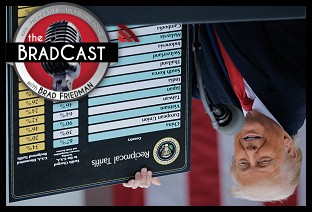

Sunday 'Don't Look Down' Toons 'Mob Boss' Trump's Global Trade Sanctions Tank U.S., World Markets: 'BradCast' 4/3/25

'Mob Boss' Trump's Global Trade Sanctions Tank U.S., World Markets: 'BradCast' 4/3/25 'Green News Report' 4/3/25

'Green News Report' 4/3/25 Dems Step Up: Crawford Landslide in WI; Booker Makes History in U.S. Senate: 'BradCast' 4/2/25

Dems Step Up: Crawford Landslide in WI; Booker Makes History in U.S. Senate: 'BradCast' 4/2/25 Judge Dismisses Long-Running Challenge to GA's Unverifiable, Insecure E-Vote System: 'BradCast' 4/1/25

Judge Dismisses Long-Running Challenge to GA's Unverifiable, Insecure E-Vote System: 'BradCast' 4/1/25 'Green News Report' 4/1/25

'Green News Report' 4/1/25 Bad Court and Election News for Trump is Good News for America: 'BradCast' 3/31

Bad Court and Election News for Trump is Good News for America: 'BradCast' 3/31 Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons

Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons 'Green News Report' 3/27/25

'Green News Report' 3/27/25 Vets Push Back at Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25

Vets Push Back at Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25 Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26

Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26 'Emptywheel': Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace': 'BradCast' 3/25/25

'Emptywheel': Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace': 'BradCast' 3/25/25 USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25

USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25 We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25

We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25 What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25

What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25 Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25

Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25 Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25

Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL