READER COMMENTS ON

"DEMOCRACY DENIED: SAN DIEGO JUDGE DISMISSES BUSBY/BILBRAY ELECTION CONTEST ON JURISDICTIONAL GROUNDS!"

(109 Responses so far...)

COMMENT #1 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:43 pm PT...

What the fuck! This totaly sucks. Where has this country gone to! Why the hell did Sand DFiego spend all that money on voting machines and holding an election when it was only an appointed position anyway!

Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr

COMMENT #2 [Permalink]

...

leftisbest

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:46 pm PT...

Never in the history of this country (oops, actually there was ONE time back in December of 2000) has a court ruling been SO wrong.

The thugs now have complete freedom to grab anyone they want, put them in office without a certified election, using highly suspicious machines that were defacto decertified, and maintain the stranglehold on power in our now certified Nazi country.

This country will never be the same. The need for election monitoring and reporting of illegal acts has never been greater. We must redouble our efforts to expose this fraud and corruption throughout the U.S. in the November 7th General Election.

God, or whomever one believes to be all-powerful (and let's hope it is not "W", but it now looks that way) help us. WE SHALL NOT CONCEDE!!!

COMMENT #3 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:48 pm PT...

I guess from all those typos you can tell how extremely pissed off I am!

I'm going for a drink - or 10 - something I don't usualy do, but this calls for it! 20?

COMMENT #4 [Permalink]

...

MrBlueSky

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:51 pm PT...

I don't know about the rest of you... but I sure could use a STIFF drink about now!

COMMENT #5 [Permalink]

...

slackmaster

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:54 pm PT...

I'll probably be heading to the Bluefoot at 30th and Upas if anyone wants to join me there.

I take it the final ruling doesn't differ substantially from the tentative one Judge Hoffman posted yesterday afternoon.

COMMENT #6 [Permalink]

...

Susan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:55 pm PT...

Is there any way to appeal the ruling in federal court? How can this be??? I just don't understand my country anymore.

COMMENT #7 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:57 pm PT...

I'd like to hear from Paul Lehto on this before I get drunk.

COMMENT #8 [Permalink]

...

Charlie L

said on 8/29/2006 @ 4:58 pm PT...

We should not expect ANY part of the apparatus of government or the corporate/fascist state or their propaganda media to offer us any solace or respite from the steady decline of our rights and freedoms.

USA 2000 = Germany 1933

USA 2002 = Germany 1935

USA 2004 = Germany 1937

USA 2006 = Germany 1939

Want to take a guess at where 2007, 2008 and 2009 will take us? I predict they will the Rethuglicans will hold power on November 7 with "surprise" and "come from behind" (albeit statistically inexplicable and contrary to pre-election and exit polls) wins. The MSM will barely speak of the irregularities and not cover any of the protests (which will be minimal, after all, FALL SWEEPS will have begun and that means new episodes of LOST and AMERICAN IDOL and who knows what other crap on TV.

Then, in 2007 the corporate media will spoon-feed the "Democrat" party their candidate of choice --- Hillary Clinton. There will be plenty of "terrorists incidents" such as the mock London bombing events and then perhaps (if necessary) another false-flag attack on the USA, and eventually, Hillary will lose by 62% to 38% (they will be sick of 51% to 49% by then) in November of 2008.

Somewhere in there the camps they have set up will start to grow in population, and it won't be illegal aliens in them. When those camps get TOO crowded, unruly, or just plain smelly, somebody will come up with the idea of a "solution" to that problem.

COMMENT #9 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:00 pm PT...

Yes, they can appeal the decision. $$$$$

COMMENT #10 [Permalink]

...

Chris Hooten

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:01 pm PT...

You have got to be kidding me!!!!!! What, we don't get to vote anymore? Or just not count them properly? This is the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard of. I think it is clear at this point that the powers that be are going to do whatever necessary to stay in power and hence out of prison. What the hell was this judge thinking???? Did they get to him, or what?

*sigh*

I'm f*cking disgusted as all hell!

And how much more obvious does it have to become before people realize what is happening?

-- Chris Hooten

How the hell can San Diego *not* be the proper jurisdiction for its own elections?

COMMENT #11 [Permalink]

...

Charlie L

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:06 pm PT...

Just another brick in the wall.

COMMENT #12 [Permalink]

...

Hank McCann

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:09 pm PT...

A miscarriage of justice. APPEAL. You cannot expect anything more than this from the most conservative area of California. Between the Union Tribune, the conservative Supervisor of Elections Haas and this Judge, they have denied our democracy. I think we need to check this Judge's bank records.

COMMENT #13 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:11 pm PT...

COMMENT #14 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:12 pm PT...

COMMENT #15 [Permalink]

...

Max-1

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:17 pm PT...

America is now more of a Republic than a Democracy. And people wonder why "E pluribus unum" was ever removed. LOL

A country feels safe thinking that the people in Office are their representatives, when in fact, fewer are "OF the Many comes One" that was freely elected By the people so that the sole representative worked For the people.

In Rome, the Republic were elites that elected themselves to represent the interests of the State. And the State at the time was not the people but all of Rome. And when America begins to elect elites to be representatives of the people, chosen by other elites to do the bidding of the State, it no longer is a Democratic society that we live in but rather a New Roman Era. Pax Romana, meet Pax-Americana.

And the Emperor's goals are just the same. Control the people and you control the resources that flow back to Rome. Control the people any brutal way fashionable at the time. And for the loyal citizens back in Rome, their prize is their safety, security, and liberty.

COMMENT #16 [Permalink]

...

Truth Seeker

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:22 pm PT...

COMMENT #17 [Permalink]

...

onyx

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:24 pm PT...

Yuri Hofmann = American traitor.

COMMENT #18 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:29 pm PT...

"Even if this Court had jurisdiction and this Election Contest were justiciable, the Contestants’ Verified Statements are insufficient. The Elections Code requires that elections shall not be set aside unless the result of the contested election would be changed if a recount were ordered. .... It appears Contestants are unable to make this showing."

So it seems to boil down to the fact that the judge doesn't think they proved their case regarding the election results.

I didn't think that was the issue here.

COMMENT #19 [Permalink]

...

gtash

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:30 pm PT...

I am not following this story closely, so I am not fully aware of the twists and turns. However, the court's statement seems clear enough to me. I know it is frustrating and flies in the face of my lay-understanding of proper procedures; but I think the solution is to start dumping legislators, targeting them for continuing bad publicity, and (if these are elected judges) voting out some judges in the bargain. The court seems to be citing appropriate precedents....damn it.

COMMENT #20 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:35 pm PT...

The judge and the laws, it seems, rely on elections that have been, or can be, proven one way or the other... like in the good old days. They aren't set up for these hackable electronic "results".

And, gtash, please pardon me yelling, but JUST HOW ARE WE GOING TO VOTE ANYBODY OUT IF WE CAN'T GET OUR VOTES COUNTED!?!

COMMENT #21 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:35 pm PT...

The only bright point in all of this is that he also turned down the SLAPP-back!

I'm leaving now to go home and have a drink - looking forward to Paul Lehto's comments on all of this.

COMMENT #22 [Permalink]

...

brock samson

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:37 pm PT...

It should be clear by now that the courts are not our friends when it comes to post-election litigation. The system is set up to weigh heavily against judicial involvement at that point. My guess is that an appeal is a waste of time and money because this opinion appears to be on firm legal ground. Only by securing voting systems and procedures can we ensure accuracy and confidence in elections. No judge in the country is going to invalidate an election based on potential security problems without direct evidence of fraud.

COMMENT #23 [Permalink]

...

Randy Gold

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:40 pm PT...

This is mindnumbing. If allowed to stand, consider this another milestone on the road to fascism.

COMMENT #24 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:45 pm PT...

Brock

I think an appeal has plenty of chance because this ruling, while on firm legal ground, does not APPLY to the case at hand. Judge could not manage to get that distinction.

COMMENT #25 [Permalink]

...

Erma

said on 8/29/2006 @ 5:59 pm PT...

Well surprise, surprise (as Gomer Pyle would say). I said this wasn't going ANYWHERE from the start and I was viciously attacked for saying that and telling the truth by the wishful-thinking crowd on here.

These neocons are not going anywhere. Period. They are in power and control to stay. Period.

As I've said before, it's time for the streets in a very big way. But no, I don't think The People are ready yet. STILL. They would rather waste their time and $$$$$$$$ on some meaningless appeal in our Injustice system. An appeal which also will go no where. Get a clue people.

COMMENT #26 [Permalink]

...

Grizzly Bear Dancer

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:02 pm PT...

FCK THIS BUSHIT.

Another clear example of an election STOLEN BY DEFAULT.

The "will of the people" DOES NOT count for nuthing ANYMORE AND U.S. DEMOCRACY NO LONGER WORKS!!!

Certification before the final votes counted.

Electronic voting machines going home with voting officials before an election.

The hurry up Bushit Fascist offense swearing in bILRAY and photo op mock UP swearing in to legitimize what???

ELECTIONS RESULTS AT ALL COSTS MANIPULATED TO ENSURE THE REPUBLICAN CANDIDATE WAS PUSHED UP.

This is NO LONGER A GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE. AS THE NEO-CON REGIME CONTINUES TO DESTROY OUR FORM OF GOVERNMENT, THE COURTS CAN NO LONGER BE CONFIDED IN TO DO THE RIGHT THING.

WHAT WE GOT NOW IS THE DEATH GRIP OF CRIMINAL RUSTER INBREEDS HOLD US HOSTAGE AT THE MERCY OF THEIR GREEDY ACT OF MISMANAGEMENT AND DESTRUCTION.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF THIS BUSHIT SYSTEM OF CORRUPTING OUR DEMOCRATIC SYSTEM OF ELECTIONS FROM ALL ANGLES IS NOW COMPLETE AND IN FULL SWING.

LYING TERRORIST bIG dICK cHENEY IS PROBABLY CORRECT WHEN HE ESPOUTED HIS OPINION YESTERDAY THAT AMERICA NO LONGER HAS A RIGHT TO PRIVATE COMMUNICATION. EITHER ONE OF THEIR PAID OFF HAND PICKED NEO-CON JUDGES WITH GIVE THEM THE RULING THEY WANT OR SIMPLY THE PEOPLE THEY HAVE INSTALLED IN CONGRESS WILL BEND FOR THEM.

FCK ALL YOU PATRIOTS AND SOLDIERS WHO FOUGHT TO PROTECT AND PRESERVE OUR FORM OF GOVERNMENT. THE bLOODY HAND OF THE LYING CRIMINALS IN THE WHITE HOUSE HAVE TOUCHED SAN DIEGO.

COMMENT #27 [Permalink]

...

Jody Holder

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:03 pm PT...

Was the Supreme Court's Roudebush V Hartke et al cited to the court.

It would seem to contradict his ruling. It clearly speaks of the power passing to Congress "after" the initial count (not to be confused with the semi-official canvass).

This ruling, if let to stand, would make any recount or contest laws void. In every federal legislative election, no matter how illegally conducted, the party in power could declare the winner prior to even a full count, and swear them in.

The recount and contest laws have specific time tables in which to be filed. If the Congress can do this prior to those timetables even being triggered, then the people of this country do not have a government of, by , and for the people. The Republican Party has seized power through their majorities in both the Senate and Congress and can make sure they retain those majorities.

We are witnessing the destruction of the America we have known from enemies within, in the name of fighting enemies from without. The end result remains the same, the destruction of our Bill of Rights and our form of government. The American people have previously joined together when attacked from outside, will the people do the same with these enemies from within?

COMMENT #28 [Permalink]

...

onyx

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:10 pm PT...

It appears that traitor Hofmann's ruling conspicuously ignores the fact that the election was conducted using illegal equipment and that California state law forbids conducting elections on de-certified election equipment.

There is no reason that state election laws should be considered outside his court's jurisdiction. All he had to do is read the laws and rule that the election was not conducted in accordance with the law and is therefore invalid.

He could then rule that his court has no jurisdiction to overturn the swearing-in and therefore remove Bilbray from office until a proper election can be conducted. That would be an issue to be brought up in the US Congress.

This makes sense to me. What just happened makes no sense, except as a Rebub trial run for November - leak the unofficial vote count, swear the Rebup in, then ignore the Internet hubbub.

The MSM fed cows won't know or care what happened.

COMMENT #29 [Permalink]

...

Julie

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:17 pm PT...

What we have here with Bilbray being sworn in by Congress 7 days after the election with the election not having been certified, nor all the votes counted is:

certification interruptus

and

vote count interruptus

I didn't read through the judge's entire decison, but it seemed to me with the caselaw that the judge cited he was saying that the court had no jurisdiction, if the Congress found the candidate was qualified to be sworn in. (That courts had no jurisdiction whether or not a candidate is qualified, only Congress). It seemed the judge did not address in his caselaw the very issue at heart of this matter--that Bilbray had not been certified at the time of his swearing in by Congress because not all the votes were counted.

It seems to me the judge just quoted a bunch of caselaw to evade the whole issue at hand. --Did I miss something by not reading the entire decision?

COMMENT #30 [Permalink]

...

Jim

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:18 pm PT...

Was this judge appointed? Is he/she insane?

Okay then, I guess it's time to storm Congress and force them to deal with it - it can't be up to just Hastert, can it?

When does the shooting start? I hope they realize that sooner or later there will be a rebellion against this kind of bullshit!

COMMENT #31 [Permalink]

...

John

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:20 pm PT...

What has happened to the United States of America? The country that was once the model for countries struggling to slip the bonds of despotism is now putting on clinics on how to steal elections.

Someone has manufactured a crisis and provided the solution in the form of electronic voting and/or vote counting machines. It's straight from Kafka that the proferred and imposed solution to the invented problem actually provides the avenue for the problem to become real.

Perhaps it's simplistic but I don't understand the difficulty. In Canada we still use paper and we mark our choices with an X. We deposit our ballots into the ballot boxes. The ballots are then counted by hand by people that very night. The results are finalized within 24 hours. Granted it does nothing to improve the quality of the candidates, but at least the crooks in parliament are crooks of our choosing.

COMMENT #32 [Permalink]

...

A Concerned Citizen

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:22 pm PT...

BB2 - You're on a roll today, I hear ya and I'm right there with you - I feel your pain. Our country is being held hostage. OUR country. Very discouraging, after all the hard work of many to PROVE the fixed (or fixable) machines are not acceptable to us, We The People, or We The Manipulated, anymore.

Very discouraging. I think we are seeing the results of the missing Treasury money and money from Iraq? One hell of a payroll to meet.

COMMENT #33 [Permalink]

...

brock samson

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:23 pm PT...

Jody says: "In every federal legislative election, no matter how illegally conducted, the party in power could declare the winner prior to even a full count, and swear them in."

That's technically true, as I understand it. Of course the eventually certified "winner" according to the official "count" (or "recount") must match the previously declared winner, or else Roudebush could then kick in, I think.

This is the election system we have, and there's no use fighting it through litigation channels. We need a complete overhaul of election law.

COMMENT #34 [Permalink]

...

Jim March

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:24 pm PT...

Ohhhhh man. This is bad.

Guys, you know what this means? It's the death of the VVPAT as a working process in Federal congressional elections. It's the death of the entire oversight process...everything, NASED, EAC, voting system certification (state AND fed), OPEN SOURCE, party oversight, public oversight, 1% audits, none of it matters. *Nothing* we can do to protect elections will be worth a damn in terms of taking back congress.

Election theft will be unlimited and unchecked in congressional races if this holds.

Democracy just died in America.

COMMENT #35 [Permalink]

...

Bev Harris

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:44 pm PT...

Disgusting.

I think we need to prepare for the possibility that we will not be able to beat the bastards using the courts.

That leaves very few options. Citizens, the direction of the pendulum cannot be reversed by chatting on the Internet. Every single citizen will be needed out in the field collecting real evidence this fall, to compel change. I do still have hopes for Bobby Kennedy Jr.'s case, but beware of the insane DNC plan for election oversight.

I have reviewed a leaked copy of this plan, and it is almost identical to Election 2004 --- telling everyone to watch the counting, not the voting, making no effort whatsoever to get real evidence (video, audio, photos, public records), organizing lawyers to supposedly step in, like they didn't last time.

Do not cede your common sense over to political parties. This is going to be up to each of us. Do not depend on someone else to organize you.

Do not pour your evidence into a funnel --- under no circumstances should you give it to just one group or entity hoping they have the best plan. Propagate everything.

Propagate everything you learn to at least seven sources, choosing different categories --- media, listserves, seed it into the public record, put it on a Web site, get it into the hands of a documentary film maker, send it to a lawyer.

We're going to need citizens on the front lines gathering real evidence (videos, audio, photos, public records) and propagating every bit of it like mad --- pick your seven sources but you no longer have time for just one.

If you get the sense that the clock is running out, it is. This is no longer a "win-lose" --- it's a reverse the pendulum swing game.

The USA right now is not for the faint of heart. Not if you want your kids to have a country left.

COMMENT #36 [Permalink]

...

leftisbest

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:46 pm PT...

Tens of thousands converging upon San Diego and protesting this assinine court decision may be a first step in getting the word out across the country that voters will not stand for having their voices silenced.

Jim March is way too prescient. I am afraid he makes very insightful observations. WE, the Election Integrity community, must recommit to our cause and recruit 10s of thousands throughout the US to put the politicians on notice that we will be there throughout the November "election" process and will not stand for this.

We must file PROACTIVE court actions to MANDATE that election officials follow the rules BEFORE the November 7th election. They MUST be held accountable, including jailing those officials who refuse to abide by the law. We must enforce the law with writs of mandamus (sp?) in as many states as possible to FORCE compliance with the law.

It is a sad day when citizens must go to court BEFORE an election to get judges to declare that election officials must comply fully with the law or face prison time. But alas, I believe it is the ONLY remaining solution at this time.

COMMENT #37 [Permalink]

...

oldturk

said on 8/29/2006 @ 6:53 pm PT...

Essentially what this court said,.. it is okay if,..

Karl Rove prints the ballots.

We place our vote on the ballot.

Karl Rove counts the ballots.

Karl Rove swears in the winning election candidate.

Karl Rove burns/incinerates all of the ballots.

Karl Rove announces to the general public who the winning candidate was.

We have no standing/there is no jurisdiction that permits us to question the validity/integrity/honesty of the above election process.

DEMOCRACY is DEAD,..

FASCISM is TRUELY ON THE MARCH.

Under the control of bu$$hco,..

this government has taken some very nasty twists and turns.

We are in some serious trouble,.. my friends

COMMENT #38 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:15 pm PT...

#13 Bluebear2,

Exactly. This is unbelievable. Unthinkable in a bonafide democracy, which of course we no longer have. HOW CAN THEY DO THIS? HOW? WHY? Power? Greed? Christ, it sickens me.

I was saving the beer for the hurricane, but it has weakened into a miserable squall. What a dismal & fitting metaphor for the state of things. So I'll also drown my sorrows for a bit. I raise my glass to you, good patriots, sad & worthy friends! I weep for our country.

I don't know if this fight is winnable. But it IS NOT OVER.

#25 Erma,

Jesus, what the hell is wrong with you?

COMMENT #39 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:29 pm PT...

Headline from RawStory:

"NYT: Ohio to destroy '04 election paper ballots: Developing..."

COMMENT #40 [Permalink]

...

Paul Lehto

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:33 pm PT...

Courts often try to protect their rulings on appeal, they don't want to suffer the embarrassment of a reversal. So, in the course of making a ruling they will give alternative bases for them. In this case, the court stated that in the alternative it didn't find that the contestant's statements were sufficient or on enough personal knowledge. This is not something the defendants pounded on too much, so it makes it more likely that it is the court trying to put a belt and suspenders on its central ruling to protect it on appeal.

If you reflect on the context of secret vote counting here where information has been systematically denied by Registrar Haas, and specifically think about the electronic vote counting itself, it is NOT POSSIBLE for the contestants statements to be based very much or at all upon personal knowledge, given how the vote counting actually occurs with electronic voting and given that the Contestants are neither Diebold employees nor are they employees of the Registrar of Voters. Even if a real whistleblower were a key witness, that would STILL not make the contestants' statements ones made on *personal* knowledge. One could read the ruling as setting up the issue of secret vote counting for appeal, given the difficulty or impossibility of anyone having personal knowledge of facts, as opposed to "information and belief" from other sources, as the court finds lacking.

I would not read too much into the alleged insufficiency of the contestants statements, which were each many pages long. There is, however another aspect of the case which is to say that substantial information was denied to us, so on that level, there could be some insufficiency of pleading things that we still don't know about. But in that case, the Registrar of Voters should not be able to stonewall the information requests, and then take advantage of that stonewalling by alleging that the contestants statements are insufficient. In part, we have a problem here of statutes passed with paper ballots in mind being applied to electronic situations.

It is also necessary, to understand the court's ruling, to read it with the briefs and requests of the defendants, which also provide the context and some of the reasons for the posture of the court's ruling. The ruling does not stand totally alone, in that regard, but must be read with the briefs of the parties and the motions of the parties in mind.

One other note, the court's statement that immediately follows this particular sentence appears not to be based on the reading of the case file or the contestants statements, but rather on a reading of some of the more limited press coverage of this issue, since for example the petition specifically alleges ballot definition error and other things that go well beyond the court's statement here: "The Contestants’ Statements and the Election Contest itself allege no more than that there was a possibility of security breaches and hacking of the voting machines used in this election. Such broad, unsubstantiated claims are not enough." There was much more than that, and in this regard readers of bradblog would be seriously misled if they took this statement at face value.

Finally, we specifically RAISED the issue of the premature swearing in prior to certification in the opening paragraphs of the Petition for Election Contest, thus raising those facts as part of our contest. We asked the Court to recognize the difference between reviewing the Constitutionality of a premature exercise of an otherwise valid power (something courts often do) and not to see the issue purely as one of jurisdiction, as invited by the defendants to do. The Court, of course, chose to see it as a question of its jurisdiction.

Although we can not peer into the Court's motivations like we can the defendants thanks to their signed briefs, sometimes trial judges send things up to the appellate courts where cases of first impression like this belong, or will inevitably end up, anyway.

COMMENT #41 [Permalink]

...

ElectionFraudBlog.com

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:33 pm PT...

When they steal the mid terms, I think the time for fixing the system is over. WE NEED A NEW SYSTEM! Time for a revolution. Civil disobedience. Shut down the banks. Shut down the malls. Shut down the economy. Be creative, be persistent. We will win, eventually.

COMMENT #42 [Permalink]

...

Mark S

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:40 pm PT...

Jim March (comment #24) nailed it.

Democracy is dead. There's no point in contributing to candidates or getting out the vote because before the votes are even counted, Congress can swear in the candidate of their choice and there is nothing anyone can do about it.

A very paranoid person might think that the only possible reason the Democratic Party's national leadership isn't screaming about this is that they have some sort of deal going, perhaps in return for supporting a totally rotten system, Diebold and Hastert might let a few DINOs and establishment (pro-war, pro-corporate, kept their mouths shut about election integrity) Dems "win." Not enough of them to accomplish anything, but enough to reward them for supporting a thoroughly rotten system.

But I'm not advocating taking to the barricades. If we can't vote with our ballots, we can vote with our wallets. That's what a lot of good folks are doing in supporting this case and others like it. Of course since we cannot rely on the courts, there are some other frontline actions we can take with our unimaginable combined purchasing power. Buy blue. Simplify your lifestyle so that you no longer have to pay taxes. Buy gas only at Citgo. Buy produce direct from the farmers at farmers' markets. Check the web, and if a company has ever donated to Republicans, don't patronize them. We can bring the system down. WE WILL BRING THE SYSTEM DOWN!

Government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from this earth.

I was in court today, by the way, and Paul Lehto did an excellent job. We couldn't ask for a better champion. His vision is clear and if the world's sole superpower is going to be undemocratic, it will be over his dead body. And ours. But we're not going to fight them on their terms, we're going to fight them on our terms. Everything they have, their investments, their corporations, the labor, the profits they make selling products, comes from us. Without us, they're just a bunch of slimy fascist goons who will end up in Den Hague with court-appointed lawyers.

COMMENT #43 [Permalink]

...

Sally

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:45 pm PT...

Hey

Just bought some cheap Wiskey. Made a complete fool of myself in the liquor store trying to inform the innocent about what has happened today. If anyone out there decides to make democracy flavoured Wiskey I'll buy it. Ofcourse you will need to prove to me you are authentic.

COMMENT #44 [Permalink]

...

cobalt

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:46 pm PT...

There aren't words to describe this situation.

America is dead.

COMMENT #45 [Permalink]

...

GWN

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:51 pm PT...

#31 John Keep your eyes open, this will begin to happen here too. Diebold has bought up the ATM machines in one of our big banks, watch for their next move. I believe Nova Scotia did test voting with machines. (will look that up)

Your middle paragraph was dutch to me?

I don't know what to say. I guess I'll repeat what OldTurk said "You are in some serious trouble,.. my friends

COMMENT #46 [Permalink]

...

Jim March

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:53 pm PT...

There may be a way to make at least some lemonaide out of this lemon.

It may be possible to convince courts that in light of this decision, citizen and political party oversight of the process has to happen ON ELECTION NIGHT, not later.

If we can get a judge to buy that, we can get pre-election injunctions mandating such things as pre-vote machine inspections, tracing Ethernet cables at the central tabulator to prevent Internet crossovers or backroom secondary tabulators, checking the Diebold central tabulator to make sure no Visual Basic (.VBS) scripts are present, getting them to split the central tabulator video signal so we can see the monitors and more. Detailed oversight plans for each type of election equipment need to be put in place.

In California we have a pre-election inspection law, EC15004. In other state we have more general observation/oversight laws - we need to push them as far as we can go. In North Carolina efforts are under way to have a geek team under Dem auspices check voting system SOURCE CODE - when that new law was put in Diebold naturally fled but ES&S is still stinkin' up the place and we do NOT know enough about them.

We REALLY need fast, election-night access to central tabulator data files from before anybody has had a chance to hack 'em. That's why the Alaska Democratic Party's lawsuit for public records of the GEMS database file is now more important than ever.

We need to find out fast just how far gone the courts are. If they are going to prevent post-election discovery of problems through this mechanism, are they also going to block oversight while the election is going on?

Because if THAT is the situation, I swear to God if I hear one more Liberal involved in this issue preach gun control I'm gonna puke on 'em. Repeatedly. After eating somethin' gross.

Anyways.

If we can find and prove enough dirt, it may still be possible to fix this peacefully. Put simply, we need to get the issue out into the open and force a public confrontation about Democracy being stolen BEFORE THE BAD GUYS ARE READY for that confrontation. Which probably means "before they've got the US military firmly on their side". We want a confrontation at a point where neither the reformers nor the corrupt have any idea what the military will do, and counter-reform is too personally dangerous to contemplate.

Study the history of Russia's last gasp of hardline totalitarianism where Boris Yeltin stopped a counter-reform at the last minute. That's more or less the best we can hope for...and then we STILL have to worry about a Putin coming along later but one thing at a time...

COMMENT #47 [Permalink]

...

onyx

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:53 pm PT...

This is not "another milestone on the road to fascism" as Randy Gold said - the road has lead us to the threshold of the gates of hell.

November will see whether we enter or find some other road.

COMMENT #48 [Permalink]

...

oldturk

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:55 pm PT...

Joan - (C) # 38

(about # 25 - Erma)

She's 290 years old,.. but full of piss and vinegar,.. has her double barrel shotgun cocked and loaded,.. and she is ready to hit the streets,.. has been for a few years now. She is eager to bayonet these Fascists and pulverize them with the butt end of her rifle. You know,.. as much as I am reluctant to admit it,.. she maybe on spot,.. a street revolution maybe the only recourse we have left to remedy this Nazi - Neocon - Madness. If the courts will not allow a civil remedy to protect our democracy,.. is boycott and violence more to their likings ? I suppose those Concentration "CAMPS" - can't sit empty for ever and ever,.. some "insurgents" and "leftists" could occupy the place real fast.

COMMENT #49 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 7:58 pm PT...

#40 Paul Lehto,

THANK YOU SO MUCH, for your comments and for your GREAT WORK!

COMMENT #50 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:04 pm PT...

Sorry, this is off-topic, but:

"Bush White House said subpoenaed by wiretap lawyers"

-Tuesday August 29, 2006

"Two attorneys representing claimants in a lawsuit over wiretapping...claim that they have sent subpoenas to the White House...

...the subpoenaes, directed to President George Bush, the Office of Legal Counsel, the Department of Justice, and the Chief Legal Counsel for Verizon, have already been sent, and should reach their targets tomorrow..."

COMMENT #51 [Permalink]

...

GWN

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:05 pm PT...

COMMENT #52 [Permalink]

...

Nancy T

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:25 pm PT...

Thank you Paul. You are a class act, a Patriot, and an honest Warrior for truth, justice, and the American way. Rest easy in speaking truth to power.

COMMENT #53 [Permalink]

...

Soul Rebel

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:33 pm PT...

Bev #35 was right: "That leaves very few options. Citizens, the direction of the pendulum cannot be reversed by chatting on the Internet."

...Time to start breaking shit

COMMENT #54 [Permalink]

...

Sally

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:38 pm PT...

#44 Cobalt

"America is dead" ? You are still alive and kicking and tommorow after you've sobered up will probably be kicking harder.

COMMENT #55 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:47 pm PT...

Well I've finally cooled down enough (I hope) to not break my new keyboard. This is still very aggravating and I'm still in shock and wondering what to do next.

Then I find this:

"Addressing several thousand veterans at the American Legion's national convention, (Fill In The Blank) recited what he called the lessons of history, including the failed efforts to appease the Adolf Hitler regime in the 1930s.

"I recount this history because once again we face the same kind of challenges in efforts to confront the rising threat of a new type of fascism" he said."

Sounds right-on for todays events doesn't it?

Did you (Fill In The Blank)?

Well here's the answer!

Sheesh!

COMMENT #56 [Permalink]

...

big dan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 8:54 pm PT...

We're now a 3rd world country. And we're supposedly bringing democracy to Iraq? All those soldiers died for NOTHING!!! The laws concerning democracy in this country, are not upheld. Voters are rendered useless by things like this, and e-vote machines, always by Republicans disenfranchinsing voters and destroying democracy in this country. Notice, only Republicans do this??? Republicans are against democracy, fuck the voter.

COMMENT #57 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:03 pm PT...

Did Bushco try out this tactic before in Afghanistan?

At least there they had to wait 30 days from declaration of the winner until he was sworn in!

COMMENT #58 [Permalink]

...

BillORightsMan

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:08 pm PT...

After reading this I imagine GOP Election Watch parties at airstrips all over the country, so the "winning" candidate can be jetted to DC to arrive by Wednesday morning Nov. 8th, 2006 to be sworn in.

Another point: since California Law was blatently broken in the case of the machine "sleep-overs", why has there not been any charges filed on THIS issue? (pardon my ignorance if this has been done already; then what was the outcome & why?)

Thank you Paul & Jim for all your hard work. I'm off to have a drink or TWELVE!

"There are four boxes to be used in defense of liberty: soap, ballot, jury, and ammo. Please use in that order."

--Ed Howdershelt (Author)

Three down? One to go?

"A little rebellion now and then is a good thing"

-Thomas Jefferson

COMMENT #59 [Permalink]

...

JUDGE OF JUDGES

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:12 pm PT...

All these Fucking Lying Corrupt republican conservative gop SCUM have got to GO ! ! ! ITMFA

Peter Werbe just said that in some state "ITMFA" was not allowed on a licence Plate.

http://www.peterwerbe.com/

COMMENT #60 [Permalink]

...

Arry

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:25 pm PT...

#51 --- There you see a problem, as many big corporations contribute to both parties. Dig far enough (or maybe not so far) and we may see why corporate Democrats are so strangely inert.

I'm gonna pull an Erma...but, right after the 2004 presidential election which was evidently stolen, I was all over the place advocating boycotts, but those who were initially enthusiastic disappeared into the woodwork...a kinda, "Don't call me. I'll call you" kind of thing. Had we been serious at the time, things might have been a bit different now... (And boycotts have to be very serious) All I can say is good luck with boycotts. I still think they should be part of our arsenal and could be very effective.

Don't discount the court appeal. It's an illogical ragged decision and could be reversed. In addition, other things can still be done in the California court system.

Also, somehow the results of the Zogby poll have to be translated into action. This is a much better background than most movements have the fortune to possess.

I think Bev Harris hit the nail on the head in her advocacy of "propagation". We have to get out of the lazy habit just doing the easy thing then going on to the next easy thing. It is particularly important because we have to work within the knowledge that our cause is widely supported (even though currently by people ignorant of what is happening.) That's why "propagation" is so important.

As so many of you are stating, we need to go to another level. I'm ready.

COMMENT #61 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:31 pm PT...

But then we must remember this is San Diego where in the 2004 Mayoral election donna Frye was robbed of a victory by the courts.

COMMENT #62 [Permalink]

...

leftisbest

said on 8/29/2006 @ 9:51 pm PT...

Jim March's remarks (#46) echo mine (#36). This concept HAS to be translated into action. RIGHT AWAY!

We MUST file for writs of mandamus in as many state courts as possible as quickly as possible. Thirty to forty five days, max, to allow for a court decision and an appeal prior to November 7th.

All we are asking [is give peace a chance]via the court filing is that the courts mandate (via a writ of mandamus) that election officials abide by existing election laws fully and completely. To enforce the writs of mandamus, the courts can further order that the writs be served on election officials by state police (or local sheriffs/police) and that the state police/local police enforce the writ by imprisioning the election officials if they continue in their behavior as law-breakers.

It must be shown that there is a pattern of disregard for election laws by a particular jurisdiction and therefore a predeliction to continue such behavior in order to make a strong case in front of the judge for issuance of a writ of mandamus.

As defined by the "'Lectric Law Library Lexicon", a Writ of Mandamus is "... a command issuing in the name of the sovereign authority from a superior court having jurisdiction, and is directed to some person, corporation, or, inferior court, within the jurisdiction of such superior court, requiring them to do some particular thing therein specified, which appertains to their office and duty, and which the superior court has previously determined, or at least supposes to be consonant to right and justice." It goes on to say:

"...This writ was introduced to prevent disorders from a failure of justice; therefore it ought to be used upon all occasions where the law has established no specific remedy, and where in justice and good government there ought to be one. Mandamus will not lie where the law has given another specific remedy."

Clearly there seems to be no other specific remedy to the problem of election officials and now the House of Representatives as well, ignoring existing laws and making up their own rules as they go along. If we DON'T take this action in as many states [and possibly local juristictions] as possible before November 7th, we may never enjoy the right to file such legal actions after November 7th.

Is anybody out there listening? Do we have a few lawyers (including Paul who is a hero to me) who might comment on this theory and approach? Why WOULDN'T we do this, and right away???

COMMENT #63 [Permalink]

...

skeptic94515

said on 8/29/2006 @ 10:04 pm PT...

We had the Nazi Party,

Then the Communist Party,

Now the Republican Party,

Goodbye democracy and good luck.

COMMENT #64 [Permalink]

...

Agent99

said on 8/29/2006 @ 10:29 pm PT...

Everybody good and sloshed now?

Never underestimate the pusillanimity of a Superior Court judge! It is time now for all good [people] to come to the aid of their country, no?

Yes.

COMMENT #65 [Permalink]

...

whig

said on 8/29/2006 @ 10:37 pm PT...

COMMENT #66 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/29/2006 @ 10:51 pm PT...

I have a headache!

Good night.

Maybe this will all be gone tomorrow.

Not!

COMMENT #67 [Permalink]

...

oldturk

said on 8/29/2006 @ 11:01 pm PT...

A-99 (C) # 64

AFFIRMATIVE

Everybody wake-up,.. let's march on Washington DC.

COMMENT #68 [Permalink]

...

Michael Collins

said on 8/29/2006 @ 11:06 pm PT...

This is a major event in the long nightmare of democracy in our great country. Justice denied is no justice at all. I read the briefs and the argument transcripts. As a debate, following each point in a flow chart, there was no question at all...the plaintiffs won, and they won big. The decision denies each and every county and state in this country control of their elections based on the abritrary decision of any Speaker of the House. Meet the new boss! More later...

COMMENT #69 [Permalink]

...

Jim March

said on 8/29/2006 @ 11:40 pm PT...

It's days like this I wish I could stomach the taste of alcohol (bleah!).

COMMENT #70 [Permalink]

...

Paul Lehto

said on 8/29/2006 @ 11:49 pm PT...

Step One: Take Zogby 92% support for public involvement in vote counting and right to information on vote counting. Take also, belief in democracy and its nature as meaning all political power originates in the people.

Step Two: Take CA 50 realities of outright election termination, election nullification, denial of information regarding elections, and assertions of absolute power.

Step Three: Compare and contrast above two items.

Step Four: Realize that there is now, unlike before, very clearcut and open contrasts.

Isn't this what is known as a winning political issue, in the long run?

It seems the only way to really beat the 92% is to help them continually and constantly FORGET that they are the 92%, or to get them to move away from the central core of election rights to watch, rights to know, and rights to supervise elections.

Hey, in the legislative branch voting records have to be published SO THE PEOPLE CAN JUDGE their representatives.

In the judicial branch, there are juries SO THE PEOPLE CAN JUDGE guilt and innocence and liability.

In the executive branch which runs elections (concerning voting, the right that protects all other rights) the people ARE NO LONGER NEEDED????

Or, perhaps the prior paragraph is really supposed to end "there is public supervision of vote counting, SO THE PEOPLE CAN JUDGE THE FAIRNESS of elections."

COMMENT #71 [Permalink]

...

MMIIXX

said on 8/30/2006 @ 12:30 am PT...

COMMENT #72 [Permalink]

...

Jim March

said on 8/30/2006 @ 1:12 am PT...

Mine eyes have seen the horror of the mangling of the vote,

These secret tabulators have us in a sinking boat,

A mix of geeks and activists try keeping us afloat,

But the HAVA bucks roll in!

Vote by touchscreen and we'll screw ya!

We've gone and rigged all the compyewtahs!

I have seen some bad code and then sometimes I see worse,

Like crooked federal lobbyists who wield a mighty purse,

Machines that jam the paper until honest voters curse,

The whole system is a sin!

Vote by touchscreen and we'll screw ya!

We've gone and rigged all the compyewtahs!

There are voting systems out there built by criminals and thieves,

They sell trash to gleeful registrars and nobody believes,

Every programmer who ponders gets a sudden case of heaves,

Toss it all in a trash bin!

Vote by touchscreen and we'll screw ya!

We've gone and rigged all the compyewtahs!

We're gonna take these junk machines and toss 'em in a pile,

With a tanker load of gasoline and light it with a smile,

It's that or watch democracy come to its final mile,

Hell no, we'll fight and win!

COMMENT #73 [Permalink]

...

calipendence

said on 8/30/2006 @ 1:24 am PT...

One has to wonder whether a judge named "Yuri" had most of his past judicial experience formerly in the Soviet Union. Certainly the results of his work today seem to also lead one to that conclusion!

COMMENT #74 [Permalink]

...

oldturk

said on 8/30/2006 @ 1:25 am PT...

It all makes more sense now,..

is this the same judge ?

====================

A judge who said he consulted imaginary mystic dwarfs has failed to convince the Supreme Court to allow him to keep his job.

Florentino Floro was appealing against a three-year inquiry which led to his removal due to incompetence and bias.

He told investigators three mystic dwarfs - Armand, Luis and Angel - had helped him to carry out healing sessions during breaks in his chambers.

The court said psychic phenomena had no place in the judiciary.

The bench backed a medical finding that the judge was suffering from psychosis.

'Dwarf dalliance'

====================

Source : Link

COMMENT #75 [Permalink]

...

what now toons

said on 8/30/2006 @ 1:33 am PT...

woah,......I can't believe it, or I don't want to believe it. Voting machines get a sleep over, nobody cares, Judges have been appointed at an alarming rate, now we see the results. 2006 cannot be a close race, every body has to wake someone up, get every body possible to the polls, this might just be our last chance. I'm trying as best I can to reach people with my political cartoons, focusing on what we are loosing, and trying to get material out there that just might reach someone new. I'm only in a small handful of papers, but it's something. I talk to all I can, everybody has to do what they can to get more voters out this November.

www.whatnowtoons.com

COMMENT #76 [Permalink]

...

Larry Bergan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 2:23 am PT...

Mr Letho has forced them to admit something EVEN BRADBLOG probably didn't want to know.

Look at the bright side. We don't even need to prove a stolen election now!

We now know what the public, (92%) REALLY wants, and ISN'T GOING TO GET!

Go out and make people angry with the UNDENIABLE TRUTH!

Don't talk to anybody without telling them a judge has ruled that we will no longer require elections in America, but will instead use machines and pretend to vote!

COMMENT #77 [Permalink]

...

Surg

said on 8/30/2006 @ 2:31 am PT...

Hey... I don't understand this country too. F. laws.

COMMENT #78 [Permalink]

...

czaragorn

said on 8/30/2006 @ 3:25 am PT...

Where is Dredd? I hope he's OK. One point, although I just got going here in Prague - what a terrible story to wake up to: this was a special election so there was no set date for the swearing in, but I seem to recall that after the November elections a considerable amount of time will pass prior to the swearing in of the new Congress. If I'm correct in this thought, then we get at least a window of opportunity to make our cases before taking to the streets, which looks more and more like the only way out of this quagmire...

COMMENT #79 [Permalink]

...

czaragorn

said on 8/30/2006 @ 4:07 am PT...

OK, here we go: a couple of slugs of vodka, some V8, a dab of horseradish, splashes of Tobasco and Worcestershire, pinches of salt and pepper, a wedge of lime, a stalk of celery... Now a toast: To Yuri Hofmann, half Commie, half Nazi scum of the Earth repugnitron bastard, may you rot in hell! There! I feel a little better already.

COMMENT #80 [Permalink]

...

David Francis

said on 8/30/2006 @ 4:50 am PT...

Yes, my friends, this is bad. In my mind it's not historically analagous to 1939, but rather 1776. Viva Revolucion! If - or rather when the November elections suspiciously flip - it will be our duty as americans to storm the bastille. I'll see you there.

COMMENT #81 [Permalink]

...

gtash

said on 8/30/2006 @ 5:33 am PT...

Agent 99

No need to yell. I know your point well enough. Maybe what we should adopt, folks, is a NON-secret ballot. In otherwords, on election day we all 1) swear out affidavits saying who we vote for and 2) wear our campaign buttons one our shirts as we enter the polling booths; 3) scream out to the top of our lungs--"okay, I'm voting for the Democrat"; 4) exit the polls after we swear out another affidavit to the DNC lawyer on hand that we voted Democratic and sign a list with a notary saying we did all this stuff that day in front of witnesses; 5) then Iif we didn't shoot digital photos of the ballot and checkmarks before we lef the curtained booth) go home and let our DNC reps tally our signatures and compare it to Rove's results.

Or else we just take local elections seriously and vote by thousands instead of hundreds to get the county board of elections officals we want.

COMMENT #82 [Permalink]

...

big dan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 6:49 am PT...

This is a bi-partisan issue, from the voters' perspective. The GOP are disenfranchizing ALL OF US!!! They should join us. Think about it: this was a Republican-voter stronghold, and the election was close...that means LOTS OF REPUBLICAN VOTERS VOTED FOR BUSBY!

REPUBLICAN VOTERS ARE BEING DISENFRANCHISED, TOO!!! If only Democrat voters were being disenfranchised, Bilbray would've won in a landslide...USE YOUR HEAD, AND USE STATISTICS, REPUBLICAN-REGISTERED VOTERS!!! THEY DISENFRANCHISED YOU THIS TIME!!!

COMMENT #83 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 7:18 am PT...

OldTurk,

Re Erma...I actually agree with her & others about taking to the streets. And I also agree that it's not about to happen right now.

What got my bloomers in a twist was her saying that she had been "viciously attacked...by the wishful-thinking crowd on here" for having said that this effort would be futile. And for telling us to "get a clue, people".

Okay, okay, very thin-skinned & pissy of me!

But jeez!!

So I apologize, Erma. Have a beer with me. Oh wait...it's 10 in the morning. Maybe tonight.

Re #39 & 71 MMIIXX,

Yes, I just read that story. There's a website trying to preserve the ballots for scrutiny:

"Save Ohio's 2004 Presidential Ballots

Before September 3rd, 2006: Destruction Day!"

link

COMMENT #84 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 7:37 am PT...

#81 Gtash,

I'd be willing to do all that. Why not? Christ! Secret voting is ludicrous at this point!!! The NSA is already in our finances, our emails, our phone records & our underwear drawer!

I know, I know, there's probably a "good reason" for keeping our votes private. What is it??

It's the secrecy that makes it so goddamn vulnerable, imho!!!

Seriously, what is the good reason???

Our voting system is supposedly the sacrosanct bedrock of our democracy. Right!

Wasn't the principle of "We are a nation of laws, not of men" supposed to be sacrosanct, too?

The voting system right now is like a dark cellar infested with rats. We need to turn on the lights, sweep it out good & open some damn windows!!!!!

COMMENT #85 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/30/2006 @ 7:57 am PT...

Joan #84said:

"I know, there's probably a "good reason" for keeping our votes private"

Well here in California if you are voting absentee you must sign the envelope you mail it back in. Not too seceret if you ask me.

COMMENT #86 [Permalink]

...

big dan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 8:26 am PT...

Brad, I know you're busy enough, but too bad you can't accompany along with stories like this, if the MSM is reporting on this important story. IE: Was this on CNN? The corporate GOP-controlled MSM isn't giving a voice to stories important to our country. Keeping us in the dark, with JonBonetRamsay 24×7 coverage, and none for things like this.

COMMENT #87 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/30/2006 @ 8:30 am PT...

Big Dan #86

I missed the national news last night, but there was nothing on the local news last night or this morning.

But as you say - Plenty about Jon Bonet Ramsay and Rumsy's little speech yesterday.

COMMENT #88 [Permalink]

...

Diane

said on 8/30/2006 @ 9:54 am PT...

#81 Gtash

I like your idea about non-secret ballots. I don't think anything will change though, until the average citizen becomes informed about the state of our elections. We have a Stanford Student visiting us. He and his parents are liberal. One is a law professor who will be working for disabled rights during her sabbatical. The other is a retired public defender who I believe is now involved in helping under privileged juveniles.

The student is bright and curious but unaware of the problems surrounding electronic voting and elections in general. He said he thinks our elections are not perfect but fair overall.

You would think the topic to election fraud would come up in a family like theirs…but like so many families they have had challenging twists of fate that have, for awhile, required intense attention. We need a quick effective way to expose the public to important issues even when they are overwhelmed by the shit that happens in life or just plain distracted and deceived by the media.

Once our student guest reads the Rolling Stone piece and recent the articles about the Busby race I’m going to give him….I’m sure he/they will see things differently. I don’t want to turn him off by being too pushy…but I’m hoping I can get him interested enough to start a conversation going with his friends

I blame the Democratic leadership for allowing this kind of ignorance to persist (even among educated “liberals”). Why is there not an ad campaign to alert and educate the American people about the terrifying state of our elections and the loss of our democracy? People could be referred to websites like Brad Blog or Velvet Revolution and toll free numbers to Congress. It needs to happen now!! We need an end run around the corporate media or people will never get the knowledge they need to bring about change.

Where are people like George Soros who care so much about open governments?

Maybe Jon Stewart, Jack Cafferty, George Clooney, decorated veterans….liberals who give a damn about our country.….conservatives who give a damn about our country …could get involved in an ad campaign.. The Repubs are excellent at using celebrity to fool the American people…Why can’t we use celebrity to give them the truth?

Speaking of right wing lying celebrities…There should be ads right NOW… connecting Arnold and his Sec. of State to the theft of our elections and electronic voting!

It seems like we are throwing away our money on candidates if the elections are rigged. We need to focus on clean elections. People might learn just how evil the Republican Party has become and the spineless democratic leadership might be shamed into speaking out.

I join all of you in being totally depressed and outraged over the judges ruling. I don’t even want to bring up the thoughts I have whirling in my brain ….So for now I’m going to donate to the Velvet Revolution, email Jack Cafferty, Catherine Crier, Lou Dobbs, Keith Olbermann, John Stewart, Steven Colbert, and then write a letter to the editor.

Oh...and then I'm going to try to breeeathe...instead of sighing all the time (which my husband never fails to point out to me).

COMMENT #89 [Permalink]

...

colinjames

said on 8/30/2006 @ 10:17 am PT...

I don't know why, but more than six years after the beginning of the end of our democracy I never cease to be amazed at the absolute bullshit that goes on at the hands of the Refuglican party, and then shocked that they get away with it. You'd think I would have learned by now... this story here, however, is on the top of the list for sheer and utter mind-numbing bullshit, we're talking soul-wrenching here! This is not the America I grew up in, if you can't smell the fascism, you are either brainwashed, stoned, or retarded. I'm gonna go beat my head against the wall now.

COMMENT #90 [Permalink]

...

chabuka

said on 8/30/2006 @ 10:25 am PT...

I remember a similar incident..when the Supreme Court swore in Bush, before all the votes were counted...in 2000...Are we gonna take this? This is what has Republicans screaming about fascism, terrorism and the like...trying every dirty trick in the book..if the Dem's take the House and the Senate....there will all manner of shit hit the fan...Rumsfeld will be held accountable for his fuck ups, Bush will be held accountable...Republican crooks and rubber stampers will be held accountable...Judges will be held accountable...you want to clean this mess up...put Dems in, good progressive Dems will hold these people accountable

COMMENT #91 [Permalink]

...

Soul Rebel

said on 8/30/2006 @ 10:53 am PT...

Big powerful magnets. Really big powerful magnets.

It's time to start breaking shit.

COMMENT #92 [Permalink]

...

Joan

said on 8/30/2006 @ 11:35 am PT...

When I consider all the outrages (of bush, cheney, rove, rice, rummy, gonzalez etc) that should & MIGHT be investigated if dems retake congress, & the consequences that should/might ensue...

It seems to me that much of it is "murky", as far as being able to prove in court; but some of these offenses are serious felonies, involving serious jail time & major disgrace.

I just cannot imagine that they will let that happen.

COMMENT #93 [Permalink]

...

MrBlueSky

said on 8/30/2006 @ 12:52 pm PT...

Brad:

Chabuka's right... when will we be appealing this ruling to a higher and clearly more competent court?

COMMENT #94 [Permalink]

...

JUDGE OF JUDGES

said on 8/30/2006 @ 12:58 pm PT...

There's something happening here

What it is ain't exactly clear

There's a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware

I think it's time we stop, children, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

There's battle lines being drawn

Nobody's right if everybody's wrong

Young people speaking their minds

Getting so much resistance from behind

I think it's time we stop, hey, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

What a field-day for the heat

A thousand people in the street

Singing songs and carrying signs

Mostly say, hooray for our side

It's time we stop, hey, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

Paranoia strikes deep

Into your life it will creep

It starts when you're always afraid

You step out of line, the man come and take you away

We better stop, hey, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

Stop, hey, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

Stop, now, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

Stop, children, what's that sound

Everybody look what's going down

For What It's Worth - 1966 - Stephen Stills

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=30W3iRL48gQ

COMMENT #95 [Permalink]

...

phil

said on 8/30/2006 @ 4:28 pm PT...

What's left for the people to do?

The electronic voting issue has been made so complex (by adding electronics) that if your not a programmer or an electronics engineer you wouldn't understand how vulnerable these electronic voting machines are.

First the Secretary of State is against us, but now the courts are against us too.

If corruption in our government is allowing felonies to be commited at every stage.

So basically we have no right to vote.

If judges are determining our election results now --- Everytime there is a question.

What's left?

Tell me when and where there has EVER been a 100% hand count on paper compared to these cracked machines.

There is no sanity check.

COMMENT #96 [Permalink]

...

DrMcBug

said on 8/30/2006 @ 5:05 pm PT...

Get ready for the "Chinese" experience.

So get to be friends with a farmer and permaculture your space.

Free your stomach with good local (organic preferred) food, and your mind, and behind will follow.

Also, recent DNA results from permafrost confirm 1918 flu epidemic was avian. Keeping soil healthy and lots of forests purifies the surroundings. When you live in mud in crises phase agriculture, it spreads disease.

COMMENT #97 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/30/2006 @ 5:09 pm PT...

Colinjames #89 said:

"I'm gonna go beat my head against the wall now."

I tried that yesterday - all I got was a headache!

COMMENT #98 [Permalink]

...

Bluebear2

said on 8/30/2006 @ 5:18 pm PT...

JOJ #94

When that song came out it fit my view of the world at the time to a tee.

Yet in my wildest imagination I never at that time thought it could get this much worse!

COMMENT #99 [Permalink]

...

lugnut

said on 8/30/2006 @ 6:11 pm PT...

1.The election process wasn't over.

2.a recount wasn't allowed.

3.diebold machines used.

4.this court had no jurisdiction.

5.This judge yuri hofmann, is simply another traitor.

6.the administration are traitors. anti- americans.

7.The msm is runned by traitors.

8.What do you do to traitors? What has been done to traitors in the past? That's right, you got it.

9.The bleeding want stop, until we give traitors what they deserve.

10.The dems will not take the house or the senate. Why? Because they are going to do a San Diego, Florida, Ohio, Georgia etc., throughout the country in November.

11.i hope you don't think traitors will give up the power they have and allow themselves to be taken out of power and prosecuted. These people will do anything to remain in power. Anything!!!

COMMENT #100 [Permalink]

...

JUDGE OF JUDGES

said on 8/30/2006 @ 6:13 pm PT...

BB2

I guess It's up to all of us to do something about it this Time.

I saw a Ned Lamont sign in Natick Mass. today . . . . . that's a mind blower. . .

COMMENT #101 [Permalink]

...

DIXIECRAT

said on 8/30/2006 @ 7:13 pm PT...

I told you so.........the legal system is not going to be the answer. Mark my words: the legal system is only going to be a diversion for "the people" which will keep everyone playing by the rules, tied-up in court, missing deadlines and hopeful while "they" think of and implement their next moves. Robert Kennedy Jr. doesn't have a chance in hell.

COMMENT #102 [Permalink]

...

Mark S

said on 8/30/2006 @ 8:36 pm PT...

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., has an excellent chance, Dixiecrat --- not of prevailing on the merits of his case, but of following in the tragic footsteps of his father and his uncle. The question is will we be shocked and stunned, or will we be expecting it and know how to react?

Chabuka, do you happen to recall who ordered the Democratic Senators, who were a majority at the time, not to sign the Congressional Black Caucus petition against certifying the fraudulent electoral votes in 2000? Do you remember who his running mate was? Do you recall who promised to see that every vote counted in 2004? We do seem to have a very short attention span. You can expect a Democratic Congress to fight exactly as hard for democracy when they're in the majority, as they are fighting for our voting rights now. Francine Busby, the Democratic candidate in the Busby/Bilbray race, was allegedly instructed by the Democratic Party not to talk about election integrity issues because it might "suppress the turnout" (meaning campaign donations --- they know our votes don't get counted).

Some Republicans not only voted for Busby, but also donated money to the CA50 litigation.

Our votes don't count. The political parties don't care. The courts don't care. When it comes to policy, Bush is the decider. When it comes to elections, Congress is the decider.

The only decision left up to us is when to utilize that fourth and ultimate "defense of liberty" box.

COMMENT #103 [Permalink]

...

Larry Bergan

said on 8/31/2006 @ 3:35 am PT...

I told everbody I met at the rallies yesterday that Dennis Hastert can now swear in whoever he wants without having a certification from the state or votes counted. It is impossible to not get a reaction from that!

COMMENT #104 [Permalink]

...

czaragorn

said on 8/31/2006 @ 8:53 am PT...

Mark S 102 - I'm afraid Bobby's gonna go the route of John Junior, Paul Wellstone, etc. ad fucking literally nauseum. ITMFA, and then send them to The Hague!!!!!

COMMENT #105 [Permalink]

...

ALLEN mERGAMAN

said on 8/31/2006 @ 9:43 am PT...

iT IS TIME WE TAKE OUR COUNTRY BACK FROM THESE CROOKS IS THE REPUBLICAN ADMIN.THIS IS THE USA AND IF WE STAND TOGETHER WE CAN DO IT.ARE WE WAITING FOR A MILITARY DRAFT TO STAND UP TO THE BUSH CRIME FAMILY? IT IS TIME TO START DOING THE RIGHT THING AND HOLDING ALL OF THEM ACCOUNTABLE.EVERYONE NEEDS TO JOIN TOGETHER TO COME UP WITH A PLAN TO TAKE ACTION.IT IS TIME FOR A CHANGE BEFORE THEY TOTALLY DESTROY OUR COUNTRY.IT IS ON ITS WAY TO DISASTER.THE LAW HAS BEEN BROKEN SINCE 2000 AND WE CAN'T WAITE MUCH LONGER.WHEN ARE THE AMERICAN PEOPLE GOING TO WISE UP? WILL IT TAKE AREVALUTION?I HOPE NOT.WHEN WILL THE DEMS GET ORGANIZED ENOUGH TO SAVE THIS COUNTRY FROM REINS.

COMMENT #106 [Permalink]

...

Lunchbox

said on 8/31/2006 @ 2:53 pm PT...

We're All Wearing The Blue Dress Now . . .

COMMENT #107 [Permalink]

...

Tired of Bushshit

said on 9/1/2006 @ 6:03 am PT...

I am sick and tired of all this Bushshit! Republicans can do whatever they want and the voters put up with it. We no longer live in a democracy we live under Hitler's rule.

I thought Senator Debra Bowen was going to hold a hearing in San Deigo. What ever happend to that?

Didn't I read that a few weeks back? I am starting to think that she is our only hope.

COMMENT #108 [Permalink]

...

Freedom Fighter

said on 9/1/2006 @ 9:57 pm PT...

"There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to ONE who is striking at the ROOT." - Thoreau

Eliminate the NON-Federal/NO-Reserve/BANK$STERS and their paper paid for Attorn-eys/Esquires (boot lickers/shield carriers).

Buy Article 1, Section 10: gold and silver coin.

DONT FEED THE BEAST

"You are a DEN OF VIPER$ and I will rout you out!" - Andrew Jackson.

HE DID.

DESTROY THE ROOT AND THE TREE OF EVIL "WHITHERS ON THE VINE".

VOTE GOLD/SILVER. It will expose the "paper money" FRAUD and will bring about the

NEW ENLIGHTENMENT.

They will ALL be EXPOSED when they have to answer the peoples MONEY questions (and the worlds)...everything else falls in line... 120 million gun owners strong...

One mans freedom fighter is another mans terrorist...

The mouths of envious

Always find another door

While at the gates of paradise they

beat us down some more

But our mission's set in stone

˜Cause the writing's on the wall

I'll scream it from the mountain tops

pride comes before a fall

So many thoughts to share

All this energy to give

Unlike those who hide the truth

I tell it like it is

If the truth will set you free

I feel sorry for your soul

Can't you hear the ringing ‘cause

for you the bell tolls

I'm just a freedom fighter

No remorse

Raging on in holy war

Soon there'll come a day

When you're face to face with me

Face to face with me

Can't you hear us coming?

People marching all around

Can't you see we're coming?

Close your eyes it's over now

Can't you hear us coming?

The fight has only just begun

Can't you see we're coming?

I'm just a freedom fighter

No remorse

Raging on in holy war

Soon there'll come a day

When you're face to face with me

Face to face with me.

Freedom Fighter - Creed

“Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value ---- zero.” - Voltaire

"While one person hesitates because he feels inferior, another is busy making mistakes and becoming superior." - Henry C. Link, writer

"Money is the most important subject intellectual persons can investigate and reflect upon. It is so important that our present civilization may collapse unless it is widely understood and its defects remedied very soon." --- Robert H. Hemphill, former credit manager, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

"I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies." - Thomas Jefferson

"Whoever controls the supply of currency would control the business and activities of the people." - President Garfield 1881. (Assinated (Lincoln/Kennedy too. Same reason.)

"Follow the YELLOW BRICK road"...in SILVER slippers... (not ruby per the movie).

YOU can ALL STRIKE THE ROOT...Vote NOW, Vote OFTEN:

DUMP THE PAPER LIES, BUY GOLD/SILVER TRUTH.

“The most successful tyranny is not the one that uses force to assure uniformity but the one that removes the awareness of other possibilities, that makes it seem inconceivable that other ways are viable, that removes the sense that there is an outside.” - Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world: Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.” - Margaret Mead

The GOLD/SILVER MONEY revolution continues...Will YOU join and save YOURSELF and America's Artilce 1, Section 10?

"He who has the GOLD (money), makes the RULES."

If not...

"When the government fears the people, you have liberty. When the people fear the government, you have tyranny." -Thomas Jefferson

“The beauty of the Second Amendment is that it will not be needed until they try to take it.”

"The 2nd Amendment is the Reset Button on the Constitution."

Dont Tread On Me

COMMENT #109 [Permalink]

...

Freedom Fighter

said on 9/1/2006 @ 10:01 pm PT...

"I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies . . . If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation, then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around [the banks] . . . will deprive the people of all property until their children wake-up homeless on the continent their fathers conquered . . . The issuing power should be taken from the banks and restored to the people, to whom it properly belongs."

- The Debate Over The Recharter Of The Bank Bill, (1809), Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), U.S.A. Founding Father to John Taylor, 1816

Dont Tread On Me

Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons

Sunday 'Great Start!' Toons Vets Push Back at Trump, Musk Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25

Vets Push Back at Trump, Musk Plan to Slash Health Care, 80K V.A. Jobs: 'BradCast' 3/27/25 'Green News Report' 3/27/25

'Green News Report' 3/27/25

Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26

Signal Scandal Worsens for Trump, GOP; Big Dem Election Wins in PA: 'BradCast' 3/26 'Emptywheel' on Why Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace' After Signal Chat Debacle: 'BradCast' 3/25/25

'Emptywheel' on Why Trump NatSec Team Should 'Resign in Disgrace' After Signal Chat Debacle: 'BradCast' 3/25/25 'Green News Report' 3/25/25

'Green News Report' 3/25/25 USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25

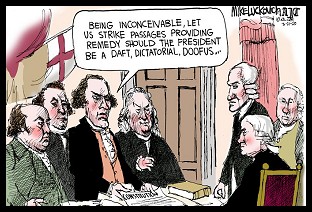

USPS 'Belongs to the People, Not the Billionaires': 'BradCast' 3/24/25 Sunday 'Suddenly Conceivable' Toons

Sunday 'Suddenly Conceivable' Toons 'Green News Report' 3/20/25

'Green News Report' 3/20/25 We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25

We're ALL Voice of America Now: 'BradCast' 3/20/25 What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25

What Trump's 'Timber Production Expansion' Means (and Costs): 'BradCast' 3/19/25 Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25

Courts Largely Holding Against Trump, Musk Lawlessness: 'BradCast' 3/18/25 Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25

Chief VOA Reporter on Outlet Falling Silent First Time Since 1942: 'BradCast' 3/17/25 Trump EPA Unveils Plans to Endanger, Sicken Americans: 'BradCast' 3/13/25

Trump EPA Unveils Plans to Endanger, Sicken Americans: 'BradCast' 3/13/25 Trump Nixed Enforce-ment Against 100 Corp. Lawbreakers: 'BradCast' 3/12/25

Trump Nixed Enforce-ment Against 100 Corp. Lawbreakers: 'BradCast' 3/12/25 Bad Day for 'Strongmen': 'BradCast' 3/11

Bad Day for 'Strongmen': 'BradCast' 3/11 WI Election Could Flip Supreme Court Control, Musk Jumps In: 'BradCast' 3/10

WI Election Could Flip Supreme Court Control, Musk Jumps In: 'BradCast' 3/10

![Click to show/hide [+]](https://bradblog.com/images/toggle_plus.gif)

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION