This morning, NPR's Weekend Edition covered the latest trouble with Diebold's touch-screen systems. They went to Pottsville, PA during last Tuesday's primary election.

This morning, NPR's Weekend Edition covered the latest trouble with Diebold's touch-screen systems. They went to Pottsville, PA during last Tuesday's primary election.

The producer on the story had contacted us last week, prior to the story, for some background information. The resultant report, aired this morning, was generally a good --- and for a chance, accurate! --- one, we think.

By way of quick summary: Diebold spokesman Mark Radke explains the latest security hole, which had caused a lockdown of all Diebold touch-screen machines in PA, just days prior to the election, was there for a good reason --- to update software quickly, he says.

No explanation, of course, for why Diebold didn't feel it necessary to warn PA themselves about such a need for these extreme measures long ago. Especially since they were warned about the problem as long ago as January 2004.

Johns Hopkins computer science professor, Avi Rubin, says he can't think of a problem ever revealed in a voting machine as severe as this one --- the one which Radke predictably downplays --- adding that a TIVO system has more built-in security than a Diebold voting machine!

Radke says the physical security of the machines would make it impossible to exploit the security hole. Radke, of course, knows he's just spinning. Rubin makes that clear in his response, explaining how he could have compromised an election in about 5 seconds as a poll worker through this ridiculous vulnerability.

-- Listen to the full report (about 5 mins) here...

...And let us know what you thought of it in comments.

UPDATE: Barb Burt over at CommonCause, blogs on the NPR item as well this morning, giving it high-marks, along with a few other notable thoughts.

UPDATE 5/24/06: A text transcript of the NPR report is now included below...

After the very, very close presidential election in 2000, when results were in doubt for weeks, Congress appropriated funds to help states modernize their voting. And companies that manufacture voting machines have rushed new computerized systems onto the market. But there are concerns about the new machines. Apart from the inevitable glitches and new equipment, critics raise questions about machines that have no paper record of votes and about the possibility that computerized systems could somehow be reprogrammed to change votes, perhaps even change the outcome of an election.

Tuesday was Pennsylvania's primary election. In the town of Pottsville, they used brand new voting machines manufactured by a company called Diebold. Pottsville is home to a Yingling and it's the county seat of Schuylkill County. Generally, voters in Pottsville liked their new Diebold machines.

Unidentified Woman: Did you see the machine before?

Unidentified Man: No.

Unidentified Woman: So push that button. Here's your actual voting page.

Unidentified Man: Just (unintelligible) vote?

Unidentified Woman: Right. Say you want that. If you don't want him, just touch it again and it erases.

Unidentified Man: Okay.

Unidentified Woman: So we have to stand back.

Unidentified Man: I found it relatively easy to use and different screens could help you go back and forth if you needed to change anything. And I thought it was very helpful, and a step forward for progress here.

Unidentified Woman: Well, it seems funny, you know. It's sort of awkward, 'cause you're use to the paper, but now I would rather do it this way.

Unidentified Man #2: 'Cause you're in the booth there and it was dark.

Unidentified Woman: And you're closed in.

Unidentified Man #2: That's right.

WERTHEIMER: Election judge Izzy Adams(ph) at Precinct 51 said things were going better than she'd expected with touch screen voting machines. But in late afternoon, when another election official appeared with the Diebold pamphlet and pin number, Ms. Adams didn't know what she was suppose to do with it.

Ms. IZZY ADAMS (Election Judge): Did you see 051606? That's a pin number. Now where did they get, see there's a lot of things yet we don't know about these. She never mentioned pin word or password, did she? Do you remember her...

Unidentified Woman No. 2: No, I don't remember, no.

Ms. ADAMS: No, I don't remember her saying anything about password or pin number.

WERTHEIMER: Several weeks ago, the nonprofit watchdog group Black Box Voting.org raised questions about the Diebold TSX. That's the machine Pottsville is using. A computer expert hired by the group reported that the machines were designed with a portal, a significant security vulnerability. Diebold spokesman Mark Radke(ph) says it is there, but it's there for a good reason.

Mr. MARK RADKE (Diebold Spokesman): When a new version of software must be loaded on the unit because of election law changes and items like this that might take place during the life of the equipment, those new versions of software are uploaded into the system through this path.

WERTHEIMER: So the portal, the door into the system, is there to update it?

Mr. RADKE: That's correct.

WERTHEIMER: Others say that may be so, but it's also a real security threat.

Professor AVI RUBIN (Johns Hopkins): I believe that this is not only the most serious security problem that I've seen in a voting machine, but I can't think of a security problem that I've seen in any kind of system that is severe as this.

WERTHEIMER: That is Johns Hopkins computer science professor Avi Rubin. He's been studying the technical aspects of the electronic voting systems since 1997. He says that Tivo, a home device that records television shows, has tighter security than the Diebold machine.

Mr. RUBIN: Now, the reason that this is a security concern is that they made it very, very easy for someone to modify that software. So easy, in fact, that all you really need is a few seconds of physical access to the machines. You could introduce something by putting a memory card inside of them that would cause the machines to be unusable without hardware repair.

WERTHEIMER: But all of these things are not networked, right?

Mr. RUBIN: Right.

WERTHEIMER: So if you got into one machine and changed things, that would be one machine in one precinct.

Mr. RUBIN: Despite the fact that the machines are not networked, you could change the software on there so that it would put a virus on the on the memory card. The memory cards are transferred from one machine to the other.

And so the thing to keep in mind is that the virus or the malicious software that's introduced, it could cause the machines to fail, but it could also do something that would be undetectable. What if the malicious software simply said, if we're in a precinct that votes a particular way that we don't like, swap 10 percent of the votes.

WERTHEIMER: Diebold's spokesman Mark Radky(ph) says that cannot happen because poll workers see to it that voting machines are securely locked away. And before each election, the machines are retested and marked with special security tags.

Mr. MARK RADKY (Diebold Spokesman): It's a very simple and clear way to validate that, yes, that unit has been tested, it is secure and it can be used for the election.

WERTHEIMER: So what you're saying is that you can secure the machines, but there is nothing inherent in the machine to protect it from being tampered with if somebody happened to be able to get at it.

Mr. RADKY: Well, if someone has direct access to a unit, just like with your PC as an example, if someone had direct access to your PC over an extended period of time, which you wouldn't let that happen, obviously, they could, you know, remove the hard drive, put a new hard drive in and so on. And unless you tested it, you would never know.

In this situation, though, every one of the voting stations is tested before every election, it's locked down as far as the security tags are concerned, and it goes through extensive testing before the memory cards are locked into the unit.

Mr. RUBIN: I don't buy that at all.

WERTHEIMER: Security expert Avi Rubin worked with Diebold machines in Maryland.

Mr. RUBIN: I worked as an election judge and I spent a whole day with these machines. At the end of the day I collected the memory cards out of them and held them all in my hand and fed them into the accumulator machine. That's how the Diebold system works. You put all the memory cards into one machine and it counts the votes off of all of them and totals them.

It would have been extremely easy for me to have another memory card, these are very small cards, up my sleeve and stick it in the machine for five seconds. And that's all I would have to do to infect the entire precinct and compromise that election.

When you take hundreds of thousands of voting machines across the country being protected in sometimes absolutely ridiculous ways like having poll workers take them home overnight, which does happen, and you tell me that the security of the whole election depends on nobody getting a few seconds of access to that machine, I think that's crazy.

WERTHEIMER: The other issue frequently raised about new equipment, including the machines Pottsville used, is that if tampering did take place there would be no way to recount the election, no record at all of how each voter voted, and at least one state has already decided that won't work.

New Mexico has a new law mandating paper ballots, which are then electronically scanned and counted. Governor Bill Richardson pushed for the new law because New Mexico had all kinds of difficulties with touch screen equipment in 2004, making it one of the last states to report results.

Governor BILL RICHARDSON (New Mexico): We became one of the laughing stock states in the country because we had these technological machines that were not working, that in several counties were defective, were slow, were unreliable, and I basically said to myself I'm not going to go through this again. And I just think that the paper ballot system, as untechnical as it seems, is the most verifiable way we can assure Americans that they're voting and their vote is counting.

WERTHEIMER: Governor Richardson told us he expects to see other states follow his lead and go for a hybrid system with paper ballots that can be tallied quickly by computers, or if necessary, more slowly by people.

But let's go back to Pottsville, PA and to people voting at the West End Hose Company Firehouse.

Unidentified Man #3: (unintelligible)

WERTHEIMER: There were a few glitches there and elsewhere around the state. In the Pittsburgh area, machines manufactured by a competitor, Electronic Systems and Software, refused to start in many polling places, and there were similar mechanical problems in Philadelphia. Those occurred with yet another voting machine manufacturer, Danaher.

This Tuesday, Arkansas holds its primary. All but three counties will use new voting machines from Electronic Systems and Software.

Is MAGA Finally Beginning to Fall Apart?: 'BradCast' 11/19/25

Is MAGA Finally Beginning to Fall Apart?: 'BradCast' 11/19/25 Trump's Terrible, Horrible,

Trump's Terrible, Horrible, 'Green News Report' 11/18/25

'Green News Report' 11/18/25

A Kaleidoscope of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 11/17/25

A Kaleidoscope of Trump Corruption: 'BradCast' 11/17/25  Sunday 'Back to Business' Toons

Sunday 'Back to Business' Toons Trump DOJ Takes Stand

Trump DOJ Takes Stand 'Green News Report' 11/13/25

'Green News Report' 11/13/25 Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Affordable' Afford-ability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12

Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Affordable' Afford-ability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12 After the Shutdown and Before the Next One: 'BradCast' 11/11/25

After the Shutdown and Before the Next One: 'BradCast' 11/11/25 'Green News Report' 11/11/25

'Green News Report' 11/11/25 Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25

Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25 Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons

Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons 'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25

'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25 'Green News Report' 11/6/25

'Green News Report' 11/6/25 BLUE WAVE! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25

BLUE WAVE! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25 Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25

Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25 Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25

Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25 A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25

A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'BradCast' 10/30/25 Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29

Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29 Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25

Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25 Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25

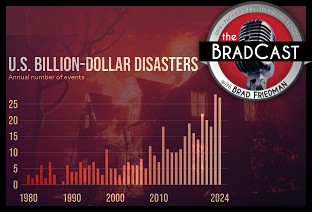

Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25 Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL