Guest Blogged by Ellen Theisen of VotersUnite.org

[Ed Note: Ellen appeared on CNN's Lou Dobbs Tonight this evening to discuss this report. The video is now posted here.]

[Ed Note: Ellen appeared on CNN's Lou Dobbs Tonight this evening to discuss this report. The video is now posted here.]

As we approach the 2008 general election, the structure of elections in the United States — once reliant on local representatives accountable to the public — has become almost wholly dependent on large corporations, which are not accountable to the public. Most local officials charged with running elections are now unable to administer elections without the equipment, services, and trade-secret software of a small number of corporations (primarily Election Systems and Software (ES&S), Hart InterCivic, Sequoia Voting Systems, and Premier Election Systems (formerly Diebold), though a few other corporations have a very small share of the market).

If the vendors withdrew their support for elections now, our election structure would collapse.

However, some states and localities are recognizing the threat that vendor dependency poses to elections. They are using ingenuity and determination to begin reversing the direction.

This week, VotersUnite.Org released a report [PDF] that examines the situation, how we got here, and steps we can take to limit corporate control of our elections in 2008 and reduce it even further in the future.

Case studies presented in our report give examples of the pervasive control voting system vendors now have over election administration in almost every state, and the consequences some jurisdictions are already experiencing. We discovered that such dependency has allowed vendors to...

- Coerce election officials into risk-riddled agreements, as occurred in Angelina County, Texas, in May 2008.

- Endanger election officials’ ability to comply with federal court orders, as occurred in Nassau County, New York in July 2008.

- Escape criminal penalties for knowingly violating state laws and causing election debacles, as occurred in San Diego, California in 2004.

Analysis of the impact of laws and decisions at all levels of government demonstrates that lawmakers and officials have facilitated the dependence of local elections on private corporations. Our report explores:

- How the mandates of the Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) and the inaction of the federal government left the states and localities with nowhere to turn but to the vendors.

- How state laws, passed by ill-informed representatives, limited the options of local officials to the voting systems developed by big corporations.

Voting system vendors’ contracts, communications, and histories explored in the report reveal that vendors exploit the local jurisdictions’ dependency by charging exorbitant fees, violating laws and ethics, exerting proprietary control over the machinery of elections, and disclaiming unaccountability.

However, even in the current vendor-dependent environment, some jurisdictions are resisting vendor control and finding ways to decrease their dependency and build an independent foundation for their election structure. See page 40 of the report for case studies that point to the power state and local election officials have to reclaim control of elections.

- More than they realize, many local election officials have the legal authority to oversee vendors and limit vendor dependency, as is occurring in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

- States can “kick the vendor out of the state” or at least stop further vendor infiltration into their elections by following the lead of Oklahoma and Oregon.

- Paper ballots allow local officials, like those in Curry County, New Mexico, to ultimately rely on their own devices and their own citizens, rather than on the high-tech devices sold by vendors. In the words of the deputy county clerk: "If necessary, we can always hand count them."

In the final section of the report, we recommend practical, concrete actions for reducing vendor dependence. Even in time for the November 2008 general election, local officials and citizens can take positive steps to oversee the vendors’ goods and services and mitigate vendor control.

Citizens — both private and public — are beginning to realize that they can and must re-assert their ownership of elections and demand transparent citizen oversight of elections.

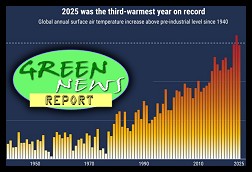

'Green News Report' 1/20/26

'Green News Report' 1/20/26

Sunday 'Domestic Terrorist' Toons

Sunday 'Domestic Terrorist' Toons 'A Cornered Rat is a Dangerous Rat': Trump Terrorizes Minn., Menaces NATO, World: 'BradCast' 1/15/26

'A Cornered Rat is a Dangerous Rat': Trump Terrorizes Minn., Menaces NATO, World: 'BradCast' 1/15/26 'Green News Report' 1/15/26

'Green News Report' 1/15/26 'This Isn't Close to Over': Mad King Trump in Venezuela (and Beyond): 'BradCast' 1/14

'This Isn't Close to Over': Mad King Trump in Venezuela (and Beyond): 'BradCast' 1/14 Things Getting Weirder as Trump Keeps Losing: 'BradCast' 1/13/26

Things Getting Weirder as Trump Keeps Losing: 'BradCast' 1/13/26 'Green News Report' 1/13/26

'Green News Report' 1/13/26 After ICE Murder in MN, Local Cops Disown Fed Policing Practices: 'BradCast' 1/12/26

After ICE Murder in MN, Local Cops Disown Fed Policing Practices: 'BradCast' 1/12/26 Sunday 'Ice Age' Toons

Sunday 'Ice Age' Toons 'Green News Report' 1/8/26

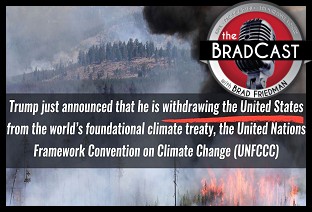

'Green News Report' 1/8/26 Trump to Congress, Climate, U.N., Rule of Law: DROP DEAD - 'BradCast' 1/8/26

Trump to Congress, Climate, U.N., Rule of Law: DROP DEAD - 'BradCast' 1/8/26 'Nonsense': Trumpers Claim 315k Fraudulent GA Votes in 2020: 'BradCast' 1/7/26

'Nonsense': Trumpers Claim 315k Fraudulent GA Votes in 2020: 'BradCast' 1/7/26 Jack Smith Testimony on Trump J6 Crimes, DOJ Weaponization: 'BradCast' 1/6/26

Jack Smith Testimony on Trump J6 Crimes, DOJ Weaponization: 'BradCast' 1/6/26 Trump War on Venez. is About Ego, Power, 'Alien Enemies Act': 'BradCast' 1/5/26

Trump War on Venez. is About Ego, Power, 'Alien Enemies Act': 'BradCast' 1/5/26 Have a Holly Jolly Somehow

Have a Holly Jolly Somehow Old Man Shouts at People from WH for 20 Minutes: 'BradCast' 12/18/25

Old Man Shouts at People from WH for 20 Minutes: 'BradCast' 12/18/25 SCOTUS' How-To on Gerrymandering on 'Eve' of Election Year: BradCast' 12/17/25

SCOTUS' How-To on Gerrymandering on 'Eve' of Election Year: BradCast' 12/17/25 Bricks in the Wall: 'BradCast' 12/16/25

Bricks in the Wall: 'BradCast' 12/16/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL