The same U.S. 7th Circuit Appeals Court panel that, in 2014, opened the door to mass disenfranchisement via Wisconsin's strict GOP-enacted Photo ID voting law ("Act 23"), has now issued a decision that could, in many instances, lead to the reinstatement of the precious right of citizens to cast votes.

The same U.S. 7th Circuit Appeals Court panel that, in 2014, opened the door to mass disenfranchisement via Wisconsin's strict GOP-enacted Photo ID voting law ("Act 23"), has now issued a decision that could, in many instances, lead to the reinstatement of the precious right of citizens to cast votes.

Specifically, the panel determined in a ruling issued last week, Wisconsin's strict photo ID restrictions may not be used to disenfranchise any voter who lacks the ability "to obtain a qualifying photo ID with reasonable effort." The appellate court has remanded the matter back to the trial court so that the District Court Judge who heard the original case can determine how to best fashion a remedy that could keep many otherwise legal and often long-time voters from being turned away again at the ballot box.

The new ruling in the Frank v. Walker case comes too late for approximately 300,000 disproportionately minority and poor voters (nearly 10% of the Badger State electorate), who may have been disenfranchised during the state's recent April 5th primary election. It is difficult yet to ascertain the precise effect the polling place Photo ID restriction had in either the Republican or Democratic Presidential primaries that day, but the restrictions had the potential to alter the outcome of those races as well as a Wisconsin Supreme Court contest. The Scott Walker-supported Republican, Rebecca Bradley, reportedly defeated independent jurist JoAnne Kloppenburg by approximately 95,000 votes. The highly controversial Bradley was thus elected to serve out a 10-year term on the Badger State's highest court after being appointed by Walker to fill a vacancy last year.

As ordered by the federal appellate court, U.S. District Court Judge Lynn Adelman may now provide a remedy for those whom ACLU attorney Sean Young described as the "most impacted" by Wisconsin's polling place Photo ID restrictions. The likely remedy was outlined by the 5th Circuit panel, which noted that the new decision was intended to bring Wisconsin's law in line with Indiana law where a voter "who contends he has been unable to obtain a complying photo ID for financial or religious reasons may file an affidavit to that effect and have his vote provisionally counted."

The court ruled the restriction on voting should not be applied to three classifications of voters for whom the plaintiffs had sought relief:

Had such a remedy been in place before the state's recent primary, voters like Eddie Lee Holloway, a 58-year-old African-American man who moved from Illinois to Wisconsin in 2008 and voted without problem there until the WI GOP's Act 23 was instituted, might not have been disenfranchised at all. Holloway, despite owning at least three different forms of ID, including his expired Illinois photo ID, birth certificate and Social Security card, was unable to obtain the required Photo ID to vote in WI, as The Nation's Ari Berman documented last week. "He’d spent $200, visited two states, and made seven trips to different public institutions" in his effort to get an ID to vote, "but still couldn’t vote in Wisconsin," Berman reported, in yet another now-all-too-common tale of longtime voters facing absurd new obstacles simply trying to cast a vote in the wake of such new voting restrictions.

But Holloway was hardly alone...

Veterans also met with voting restrictions in WI

The plaintiffs in the ACLU's WI case had also sought a ruling from the 7th Circuit panel that would have mandated that the state accept ID cards issued by the U.S. Department of Veterans' Affairs (VA) as a sufficient form of identification for the purposes of casting a ballot. That point was at issue back in 2015 when the U.S. Supreme Court, sans explanation, declined to grant a hearing in the case. Dale Ho, the Director of the ACLU's Voting Rights Project, expressly included VA ID cards as an issue that the plaintiffs planned to litigate in further proceedings.

The plaintiffs in the ACLU's WI case had also sought a ruling from the 7th Circuit panel that would have mandated that the state accept ID cards issued by the U.S. Department of Veterans' Affairs (VA) as a sufficient form of identification for the purposes of casting a ballot. That point was at issue back in 2015 when the U.S. Supreme Court, sans explanation, declined to grant a hearing in the case. Dale Ho, the Director of the ACLU's Voting Rights Project, expressly included VA ID cards as an issue that the plaintiffs planned to litigate in further proceedings.

Despite being well aware of the VA identification card issue, neither Wisconsin's Republican-controlled legislature nor its Republican Governor Scott Walker took any steps to prevent the disenfranchisement of veterans who had put their lives on the lines to protect our democracy prior to last February's Wisconsin Supreme Court primary election.

Immediately after that election, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley mailed a letter to Gov. Walker. She informed him that her 90-year-old uncle Leo Olson, an Iwo Jima combat veteran, had been denied the right to vote because election officials would not accept his VA card as a sufficient form of identification.

The legislature and governor swiftly acceded to her complaint, though not in time for last February's local primaries. On March 16, Walker signed a new law that compels Wisconsin's election officials to accept VA cards as a sufficient form of ID needed to cast a vote. That relieved the 7th Circuit panel of the need to address this issue.

While any ruling that would ameliorate the harsh impact of Wisconsin's polling place Photo ID restrictions will no doubt be welcomed by voting rights advocates, the new ruling falls well short of a complete remedy for the damage wrought by this same panel's earlier decision which overturned Judge Adelman's trial court ruling, finding that WI's law was a violation of both the federal Voting Rights Act, as well as the U.S. Constitution.

Seeing the light? Not really.

Last week's new ruling was, ironically enough, authored by Judge Frank H. Easterbrook, a member of the radical right wing Robert Bork-founded, Koch Brothers-funded "Federalist Society". In 2014, Easterbrook authored the panel decision [PDF] that had overturned a the permanent injunction that Judge Adelman issued after a full trial on the merits.

Last week's new ruling was, ironically enough, authored by Judge Frank H. Easterbrook, a member of the radical right wing Robert Bork-founded, Koch Brothers-funded "Federalist Society". In 2014, Easterbrook authored the panel decision [PDF] that had overturned a the permanent injunction that Judge Adelman issued after a full trial on the merits.

Easterbrook's previous decision was so extraordinarily partisan, factually deficient, riddled with errors and legally flawed that it caused the ordinarily staid U.C. Irvine election law Prof. Rick Hasen to tweet: "I rarely just rant in my blog posts. But Judge Easterbrook caused me to blow a gasket." He added soon thereafter, "I may have to go out for a run after the Easterbrook opinion on WI voter id. Or take a shower."

Despite the likely encouraging benefits to voters in the new ruling, the new panel decision is, nonetheless, fraught with intellectual dishonesty. "Plaintiffs now accept the propriety of requiring photo ID from persons who already have or can get it with reasonable effort," Easterbrook writes, "while endeavoring to protect the voting rights of those who encounter high hurdles."

Plaintiffs did not accept "the propriety" of Wisconsin's Photo ID law because they were now convinced by Easterbrook's earlier reasoning. They advanced their alternative theory in this new challenge because they were forced to accept the premise of Easterbrook's earlier controversial panel decision thanks to a legal doctrine known as the law of the case. Once Easterbrook's earlier opinion became final, the plaintiffs could no longer make the argument that Wisconsin's photo ID law violated the Voting Rights Act or the U.S. Constitution per se. They were forced to argue that the specific issues now before the court --- VA identification cards and the rights of voters who could not "obtain a qualifying photo ID with reasonable effort" --- had not been addressed by the earlier decision.

The new appeal came about because Adelman, with good reason, thought these "new" arguments had indeed been a part of Easterbrook's earlier ruling. After all, the issue now decided had been a central feature of the case when the initial class action complaint against the WI GOP's voting restriction was filed by the ACLU in 2011.

The lead plaintiff, then 84-year-old Ruthelle Frank, had been a lawful resident of Brokaw, WI since her home birth in 1927. Although she had voted in every election since 1948 and was an elected member of the Brokaw Village Board, she learned that she faced possible disenfranchisement because she lacked one of the official photo IDs mandated by the state's new vote-suppressing photo ID law.

Frank was born at home, without a birth certificate, and was being forced to pay $20 to get one in order to obtain her supposedly "free" ID to vote. But even that was not enough. She learned she would not be able to comply with the state GOP's Photo ID restriction unless she coughed up upwards of $200 to amend the Register of Deeds record of her home birth. That record had misspelled her maiden name. Hers was precisely the type of undue burden that Easterbrook now says may not be lawfully imposed by the Wisconsin's Photo ID law.

Undue burden

In his post-trial decision, Judge Adelman expressly recited that he was addressing "the Frank plaintiffs' claim that Act 23 [the Wisconsin Photo ID law] places an unjustified burden on the right to vote and the claim...that Act 23 violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act."

In his earlier decision, Easterbrook appeared to dismiss this issue by belittling voters who are too lazy to "scrounge up a birth certificate."

In his new decision, Easterbrook again relies on the Supreme Court's plurality opinion in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008). He argues that Crawford stands for the general proposition that polling place Photo ID laws do not impose a "substantial burden on the right to vote" and that the undue burden issues raised this time by the plaintiffs were not part of the issues disposed of by his earlier panel ruling in Frank.

Adelman and half the ten (10) jurists then serving on the full 7th Circuit did not subscribe to this expansive view of the Court's decision in Crawford. In an erudite dissent, Judge Richard A. Posner noted that the plaintiffs in Crawford had simply failed to produce evidence that the Indiana Photo ID statute imposed an undue burden upon the right to vote. Posner, a well-respected and oft-cited Reagan appointee, would know. He was the author of the 7th Circuit panel decision in Crawford, the 2008 Indiana ruling upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

By contrast, according to Posner, who has since come to see the error of his early opinion, a significant and sizable minority of voters do not possess the requisite forms, not because they lack a desire to obtain them or to vote, but because of a "litany of obstacles" preventing voters who lack them from obtaining so-called "free" voting IDs from the state, as detailed by the District Court in Wisconsin after a full trial on the merits. Such obstacles include the time, expense and burdens of obtaining underlying documents needed to obtain those "free" IDs, such as birth certificates, passports and citizenship papers, the cost of which, even when adjusted for inflation, far exceeds the $1.50 poll tax that was struck down by the 24th Amendment in 1964.

Perhaps the most troubling issue, especially since Easterbrook's opinions will be cited by attorneys defending Photo ID laws passed by other states, lies in his failure to recognize that such laws do not serve a valid state interest.

"The evidence at trial," according to the trial judge Adelman, "established that virtually no voter impersonation occurs in Wisconsin. The defendants could not point to a single instance of known voter impersonation occurring in Wisconsin at any time in the recent past."

GOP claims of "voter fraud," Posner added in his dissent to Easterbrook last year, are but "a mere fig leaf for efforts to disenfranchise voters likely to vote for the political party that does not control the state government"...

Posner then demolished Easterbrook's earlier claim that "voter fraud" had been established as a "legislative fact."

Ernest A. Canning is a retired attorney, author, Vietnam Veteran (4th Infantry, Central Highlands 1968) and a Senior Advisor to Veterans For Bernie. He has been a member of the California state bar since 1977. In addition to a juris doctor, he has received both undergraduate and graduate degrees in political science. Follow him on twitter: @cann4ing

Trump DOJ Takes Stand

Trump DOJ Takes Stand 'Green News Report' 11/13/25

'Green News Report' 11/13/25

Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Afford-able' Affordability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12/25

Mamdani's 'Surprisingly Afford-able' Affordability Agenda for NYC: 'BradCast' 11/12/25 After the Shutdown and

After the Shutdown and 'Green News Report' 11/11/25

'Green News Report' 11/11/25 Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25

Victories for Democracy in Election 2025; Also: 7 Dems, 1 Indie Vote to End Shutdown in Senate: 'BradCast' 11/10/25 Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons

Sunday 'Ass Kicking' Toons 'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25

'We Can See Light at the End of the Tunnel' After Election 2025: 'BradCast' 11/6/25 'Green News Report' 11/6/25

'Green News Report' 11/6/25 TEAM BLUE TRIUMPH! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25

TEAM BLUE TRIUMPH! Dems Win Everything Everywhere All at Once: 'BradCast' 11/5/25  Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25

Repub Thuggery As Americans Vote: 'BradCast' 11/4/25 'Green News Report' 11/4/25

'Green News Report' 11/4/25 Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25

Last Call(s) Before Election Day 2025: 'BradCast' 11/3/25 Sunday 'Close Enough' Toons

Sunday 'Close Enough' Toons A Pretty Weak 'Strongman':

A Pretty Weak 'Strongman': 'Green News Report' 10/30/25

'Green News Report' 10/30/25 Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29

Proposal for 'Politically Viable Wealth Tax' Takes Shape in CA: 'BradCast' 10/29 Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25

Monster Storm, Endless Wars, Gamed Elections: 'BradCast' 10/28/25 Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25

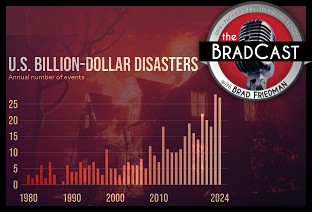

Let's Play 'Who Wants to Be a U.S. Citizen?'!: 'BradCast' 10/27/25 Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25

Exiled NOAA Scientists Resurrect Critical Disaster Database: 'BradCast' 10/23/25 Trump-Allied GOP Partisan Buys Dominion Voting Systems: 'BradCast' 10/22/25

Trump-Allied GOP Partisan Buys Dominion Voting Systems: 'BradCast' 10/22/25 Trump, Republican Law(lessness) & (Dis)Order: 'BradCast' 10/21/25

Trump, Republican Law(lessness) & (Dis)Order: 'BradCast' 10/21/25 Celebrating 'No Kings': 'BradCast' 10/20/25

Celebrating 'No Kings': 'BradCast' 10/20/25 SCOTUS Repubs Appear Ready to Gut Rest of Voting Rights Act: 'BradCast' 10/16/25

SCOTUS Repubs Appear Ready to Gut Rest of Voting Rights Act: 'BradCast' 10/16/25

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL